Last updated on February 11th, 2022 , 07:20 am

Jump To

When compared to stock trading, options trading can offer investors leveraged exposure to a security. This exposure is accessed by buying call or put options. Both of these option types typically represent 100 shares of an underlying stock. The premium paid for these derivatives, however, costs only a fraction of what buying 100 shares of the actual stock would cost.

It is because of this 100:1 ratio that option contracts can sometimes react quite explosively to only minor fluctuations in the underlying stock price. There are a lot of factors that go into determining how options react to environmental changes, and the Greeks go over each of these risk metrics.

This article, however, is going to focus specifically on leverage in options trading.

In order to understand option leverage, we must first understand how and why options contracts are “Standardized.”

TAKEAWAYS

- When compared to stocks, options offer investors much greater leverage.

- Like stocks, options contracts can be bought or sold. The holder (owner) of an option contract has the right to either purchase stock (calls) or sell stock (puts) at the contract’s strike price

- All option contracts are “Standardized”

- Option type, strike price, expiration, and share representation are all standardized

- Options are leveraged at a ratio of 100:1, meaning one option represents 100 shares of stock. This leverage increases risks

Standardized Contracts

Quite some time ago, options contracts became standardized. This standardization process helped produce a trading environment that is both liquid and easily regulated.

The below are the standardized terms of all option contracts.

- Option Type

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

- Share Representation

Let’s take a brief look at each of these now.

1. Option Type

All option contracts are either calls or puts:

Call Options give the purchaser right (but not the obligation) to purchase 100 shares of a stock at a specified strike price on or before a set expiration date.

Put Options give the purchaser the right (but not the obligation) to sell 100 shares of a stock at a specified strike price on or before a set expiration date.

2.) Strike Price

All options contracts have a strike price. This is the price at which stock can either be bought (calls) or sold (puts) should the long option purchaser decide to exercise their right.

3.) Expiration Date

Options are decaying assets. Each and everyone will expire at some point in the future. Expiration dates can range from days to years into the future.

4.) Share Representation

Almost all option contracts give the owner the right to purchase (calls) or sell (puts) 100 shares of an underlying stock at the specified strike price. There are a few exceptions to this rule, which we will soon get into.

New to options trading? Learn the essential concepts of options trading with our FREE 160+ page Options Trading for Beginners PDF.

Why Are Options Standardized?

All option contracts incorporate the above terms. Why is this advantageous?

Let’s say you want to create a contract that allows you to sell 13 shares of AAPL at exactly 176.43 on or before January 14th.

These are very specific terms. It would take time for your counter-party to decipher these terms before agreeing to them. Additionally, since these terms are so custom-tailored, the regulation would be impossible. How can an agency take the time to look at every one of these contracts individually?

They couldn’t. There are indeed custom-tailored contracts between parties, but these are known as “swaps”, and are often exchanged between large financial institutions.

The standardization of options offers investors 2 great advantages:

1. Liquidity

Liquidity is the ease with which a position can be entered and exited. Since terms like the strike price and expiration date are set in options, market makers already know what they are dealing with the second an order is received. Fills are usually instantaneous for this reason.

2.) Regulation

The regulation of the options market eliminates counter-party risk. If these financial instruments weren’t regulated, they would behave more like “swaps”, which present substantial counter-party risk. In options trading, The OCC guarantees that a counter party (or broker) will make good on the terms of the contract.

Now that we have the elementary stuff down, let’s take a closer look at option leverage!

Option Leverage in Action

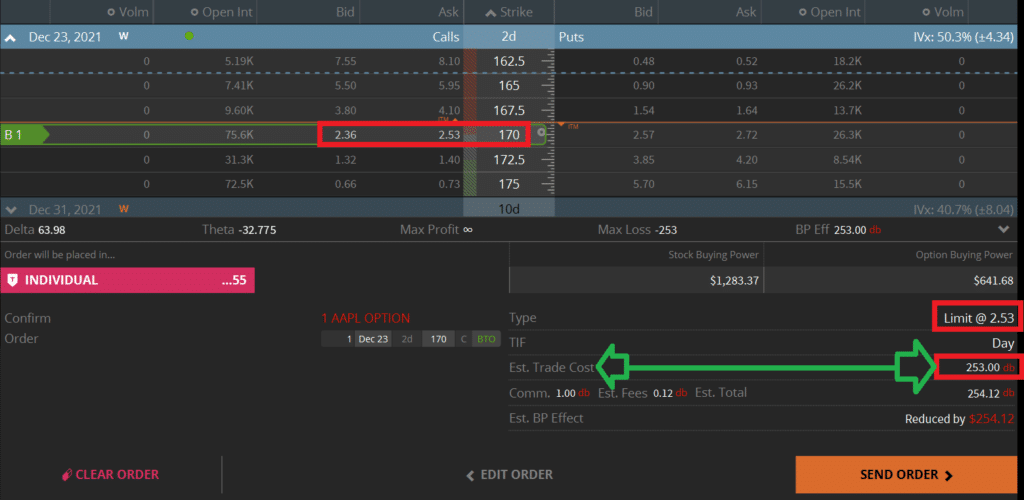

Take a look at the below options chain for Tesla (TSLA).

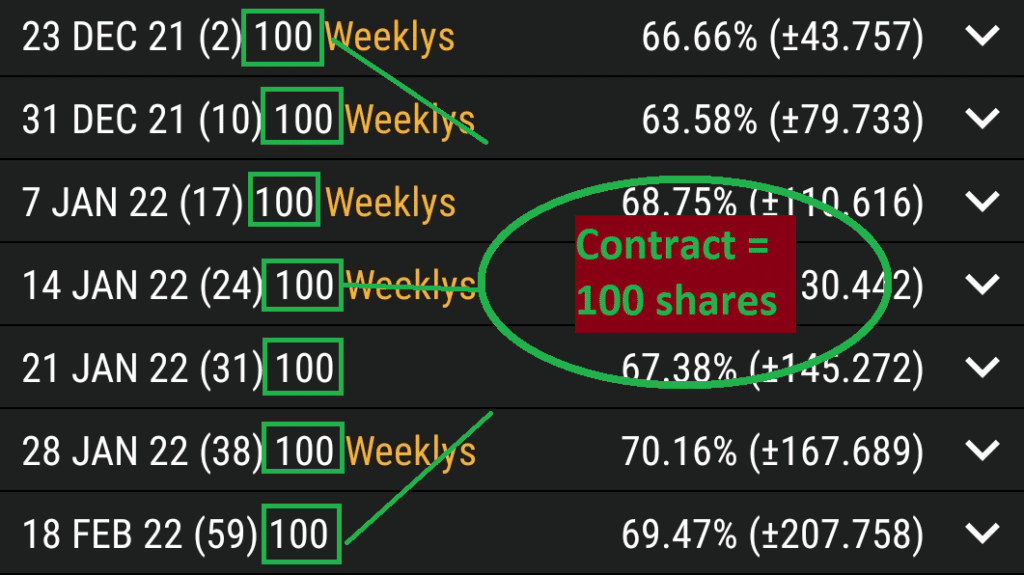

TSLA Options Chain

The squared number tells us that every option under that expiration cycle represents 100 shares of stock. This is the standardized share representation for one option contract, be it a call or put.

However, one option contract does not ALWAYS represent 100 shares of stock. When the stock of a company (or ETF/ETN) splits, that means that the outstanding options will no longer represent 100 shares of stock. All new options will, but the pre-existing ones will be “adjusted”.

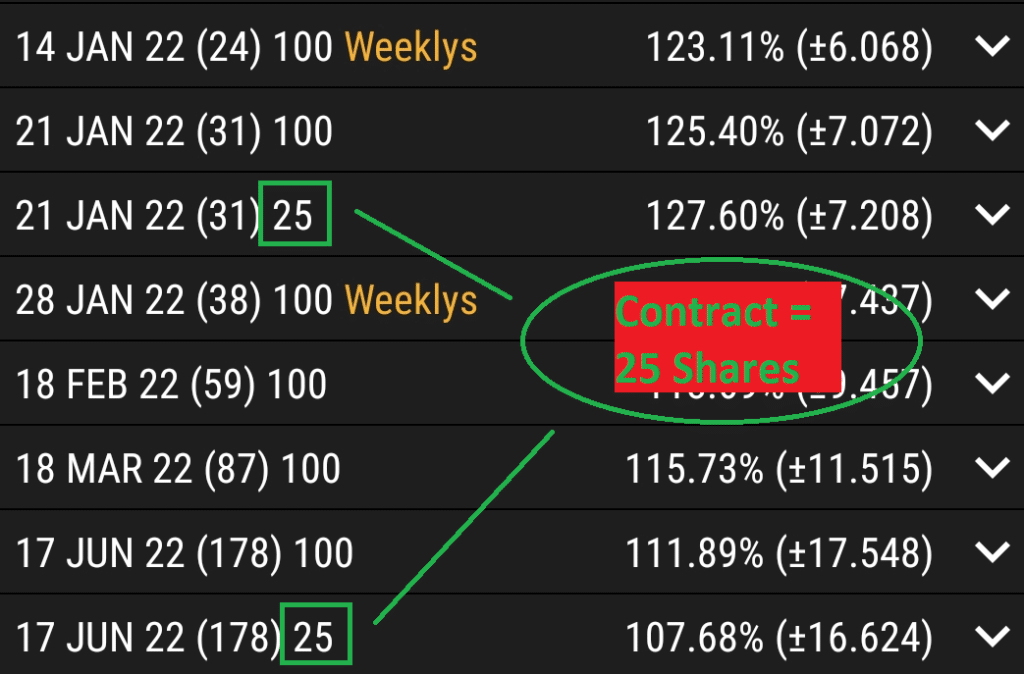

One particular ETN (exchange-traded note) that splits quite frequently is VXX. Take a look at the adjusted options of VXX, which are mixed in with standardized options.

VXX Options Chain

For a few of the above expiration cycles, we can see that one options contract represents not 100, but 25 shares of stock. These are tricky options to trade, and I avoid them for this reason.

But no matter how many shares an option represents, its quoted price must always be multiplied by 100 in order to determine its true dollar cost.

This brings us to our next topic: the cost of options.

Determining The Cost of Options

Take a look at the below options chain.

By looking at the top of the above options chain, we can see that the quote “ask” price of the 170 call option is 2.53.

So would it cost us $2.53 to purchase this option? I wish. In order to determine the true out-of-pocket cost for any option, we must move the decimal point two places to the right.

As we can see in the lower part of the image, the true cost of this trade is $253. This is because of the “multiplier effect”. Since a call or put contract gives the buyer the right but not the obligation to either buy (call) or sell (put) 100 shares of a stock, we must multiply this number by 100.

If options represented only one share of stock, this call would cost us $2.53. But, as we are learning, options are standardized contracts.

Utilizing Leverage

Because of their highly leveraged nature, options offer investors two advantages over stocks:

- Magnified profit (and loss) potential

- Less principle risk

Let’s examine each of these individually.

Options vs Stocks: Return Potential

Sometimes, it is possible to make more on an option than a stock should that stock move in a direction that is favorable to the option.

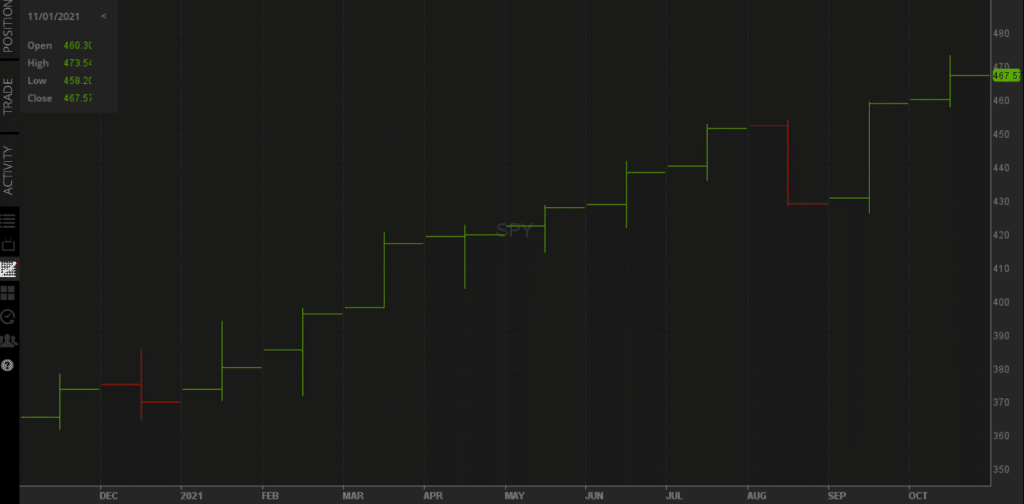

Let’s take a look at an example employing a LEAP (long-term equity anticipation securities) which is simply an option that expires greater than one year from the present.

Let’s assume one year ago today we were bullish on the overall market. We purchased a LEAP on SPY, which is an S&P 500 tracking ETF.

The below image shows the performance of our option.

We can see that we originally purchased this option for about $5, for an out-of-pocket cost of $500. SPY had a fantastic year, and we can see towards the end of the options life our call was trading at $40 ($4000).

That means we netted a return of about 700%. Not bad!

How would we have done if we purchased the stock instead? Let’s look at that outcome next.

SPY Stock: One Year Chart

So we can see that we would have made money on the stock as well. But not nearly as much! The stock would have netted us a solid return of 28%. This pales in comparison to the performance of our LEAP.

It is important to note that 2021 was a VERY bullish year. These types of returns are not normal for options. Remember, if the stock had gone nowhere, we would have lost our entire premium of $500 on the call, but our stock position would still be at breakeven.

Options vs Stocks: Principle Risk

If we were to purchase 100 shares of AAPL, that would currently cost us $16,900. If we were to purchase an at-the-money call option on AAPL expiring next month, however, that would only cost us $600 presently.

What is our maximum risk on the stock? Since any stock can go to zero, our maximum risk here is our entire investment of $16,900.

The maximum loss on any option purchased is the debit paid. Therefore, the most we can ever lose on our option is $600.

So maximum risk is indeed reduced when buying options as opposed to buying stock.

However, in order for our option to be profitable in a month, we need the stock to go up quite a bit in value. If the stock is unchanged in a month, we will lose our entire $600. Now if we bought stock instead of that option, we would have neither made nor lost money if the stock was unchanged in a month.

Additionally, it is very unlikely we will realize a maximum loss on AAPL stock. It is very likely, however, that we will realize a maximum loss on our options contract.

It is important to note that 2021 was a VERY bullish year. These types of returns are not normal for options. Remember, if the stock had gone nowhere, we would have lost our entire premium of $500 on the call, but our stock position would still be at breakeven.

Final Word

Options are great tools to help diligent traders capitalize from a future potential movement in a stock price. There is a reason, however, that most retail options traders lose money.

For every day that a stock (or ETF, index, etc.) doesn’t move in your direction, your long option contract will decrease in value. This is known as “theta” and is one of the options Greeks. Understanding these vital risk management metrics are often ignored by beginner traders.

Option trading is not free money. Most of the profits made in options trading is done so by selling options rather than buying them.

Next Lesson

projectfinance Options Tutorials

Mike Martin

New to options trading? Learn the essential concepts of options trading with our FREE 160+ page Options Trading for Beginners PDF.