Last updated on March 18th, 2022 , 04:34 am

Options trading is complicated stuff. Period. There’s no way around this. There is a lot to learn.

So what’s the best way to approach any complicated subject? By breaking it down into its parts of course. That’s what we hope to do here.

If you feel overwhelmed when going through the proceeding material, just remember that you’re not alone – almost all newbie option traders struggle when they first start. I know I did. After working as an options broker in Chicago for fifteen years, I’m still learning new things about options trading. Truly understanding how financial derivatives trade goes beyond the definition of simple calls and puts.

Options Trading is NOT Stock Trading

Let’s get this out of the way immediately: options trading is not stock trading. If you wanted to go long Tesla (TSLA) equity you’d simply buy the stock.

If you wanted to establish a bullish position on TSLA via options trading, you’d have about 10 million combinations of calls and puts to sift through.

It is because of this vastness that options trading is more of an art than a science.

If options trading is therefore considered both a language and art, then the best practitioners of this language are artists.

Now perhaps you don’t have to be the “James Joyce” of options trading to make money, but you do have to acquire a certain fusion of creative and mathematical artistry.

This article is huge. It was written as a complimentary guide to Chris Butler’s “Options Trading for Beginners,” which has become the go-to options training guide for beginners on YouTube. There is a lot within it. If you prefer to watch the video, or simply want to supplement your education, feel free to check it out below!

Options Trading for Beginners Video

In this guide, we will teach you the most important option trading concepts and ideas through the usage of numerous visualizations, explanations, and real-world examples.

So let’s get right into it!

Basic Option Characteristics

Let’s start by taking a look at a few characteristics that all options contracts have in common. Understanding these key characteristics will also help you understand how options (financial derivatives) differ from stock (equity).

- 1. All Options Expire

- Unlike stock, all option contracts expire. Once this date (known as the “expiration date”) passes, the option contract is invalid. They cease to exist. Stocks, on the other hand, never expire.

- Since all option contracts expire, this means you must choose the “duration” of your trade. What are your choices? Many. You can trade options expiring today, or you can choose to trade options that expire years from today! These “long-term” contracts are known as “LEAPS” (more on these later).

- 2. All Options Have a “Strike Price”

- In addition to having an expiration date, an options contract must have a “Strike Price” An option is converted to stock at this strike price.

- If you own a “call” option with a strike price of $105, you can convert that option to stock at the price of $105 per share. How would this be useful? Let’s say that the stock you bought the call on is trading at $120/share. Would you rather buy the stock at $120/share or $105/share?

- 3. All Options have an “Options Contract Multiplier”

- The option contract multiplier is the number of underlying shares an options contract represents.

- Usually, options have a 100 contract multiplier.

The “multiplier” concept really must be understood intuitively before we can proceed. Let’s take a moment to look closer at this characteristic that all options contracts possess.

Option Contract Multiplier Introduction

We spoke earlier of breaking down a whole into its parts. That will come in handy here. Let’s start with a stock comparison.

If you wanted to purchase one share of stock trading at $120 per share, it would cost you exactly $120. Simple enough.

Options contracts operate differently. An option is not stock; an option is a contract that allows you to either buy or sell stock.

We know already that an options contract has an expiration date and a strike price. But how many shares does an options contract represent?

Typically, the “Options Contract Multiplier” is 100 shares. This means that owning one options contract gives you the right to either buy (for a call) or sell (for a put) 100 shares of stock, at a specific strike price, by a specified date.

Why is it 100 shares? Because this value makes options trading “standardized”. If all options contracts represent a different amount of underlying stock, wouldn’t that be a nightmare?!

This “multiple” trait of options also somewhat complicates options pricing. To get the true value of an option, we must therefore multiply its quoted price by 100.

Options Contract Multiplier Example

Since a call or put option almost always represents 100 shares of stock, how much money would it cost you to purchase an options trading at a current market price of $5?

- Option Price: $5.00

- Option Premium: $500

An option quoted at $5 would cost you $500 to purchase. In reality, all you need to do is move the decimal point two places to the right. Though this may seem complicated at first, it’s quite intuitive once you understand how the “multiplier” factor works.

So now that we understand the core characteristics of options trading, let’s build on our knowledge and discuss the two different option types.

Call Option Introduction

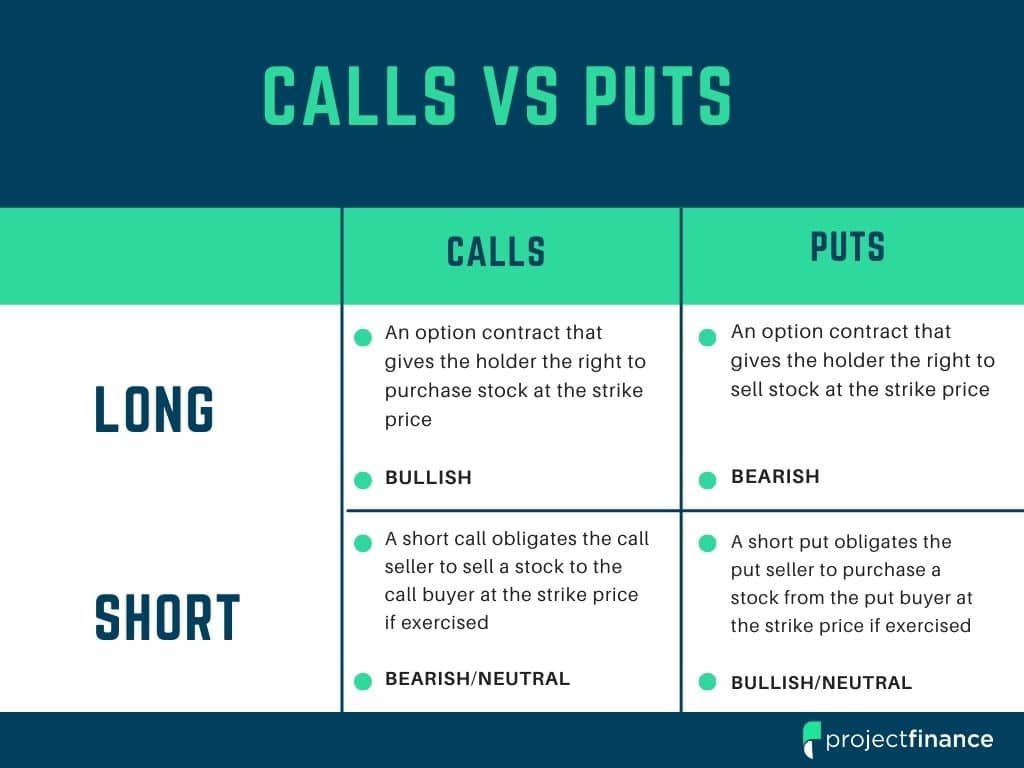

All options contracts fall under the category of calls and puts.

We are going to first explore call options. Remember, options are “derivatives”. Their value is derived from the value of their representative stock. You can’t simply own a “call option”; you must own a call option on an underlying stock or index. For example, you can own a Tesla (TSLA) $750 strike price option contract.

So what is a call option exactly?

Call Option Definition: A call option (or simply “call”) is a financial instrument that allows an investor to purchase 100 shares of stock at the strike price specified within the options contract (strike price) on or before the expiration of that option.

So what does that mean? Let’s take a look at the characteristics of a call option now to better understand this. Don’t worry if this fly’s over your head; next on our list is a simplified analogy.

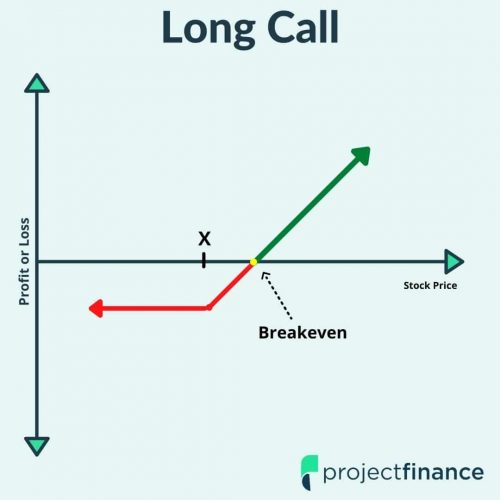

- At a very high level, the price of a call option will increase with a corresponding rise in stock price.

- The price of a call option will decrease with a corresponding decrease in stock price.

- As the stock price increases, this ability to buy the stock at a cheaper price becomes very valuable to the owner of a long call option. Wouldn’t you rather purchase stock at a steep discount if that stock were currently trading much higher?

OK, so this is the textbook explanation of a call option. Chances are, you still have more questions. Let’s move onto the “house-buying” analogy now to really drive home how call options work.

Call Options Simplified Example #1: Buying A House

Perhaps the best way for new options traders to understand how calls work is the house buying analogy

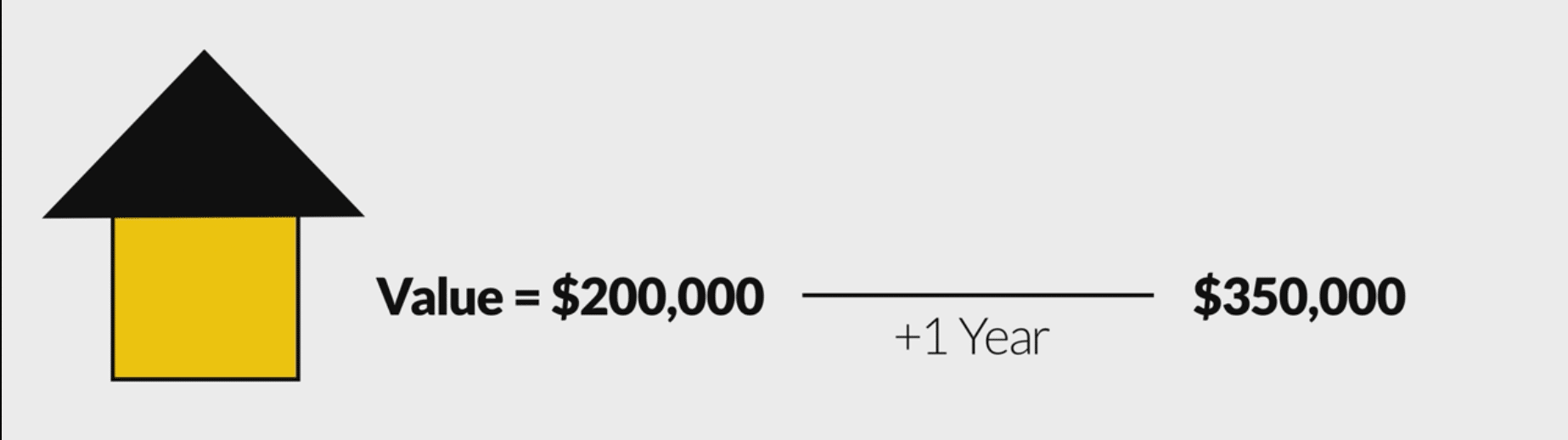

Let’s say you are in the market for a home. You find a house for sale that interests you. You think the home will increase in value, therefore you believe it to be a good investment.

However, at this point, you don’t have the liquidity necessary to purchase the home. We’ll say the cost of this home is $200,000. You can’t buy it today, but you’d like to have the option to buy that home between now and two years from now.

In the real estate market, you would be out of luck.

Let’s pretend for a moment that the housing market works as the options markets work. First off, let’s take a look at our inputs.

We have a “strike price”, which is $200,000. Additionally, we have an expiration date, which is 2 years away (when our contract will expire). Since we already know what these terms mean, let’s go ahead and make an options contract!

So what “trade details” do we have so far?

Strike Price: $200,000

Option Expiration: 2 Years From Today

The above “call option” that we just created gives us the right to purchase that house in 2 years from today (or sooner) for a price of $200,000.

Sounds like a good deal to us! But what about the seller of that home? Think they would agree to this? Heck no! What if the house price falls; you’re not entitled to purchase the house. This makes zero sense to the seller.

Ok. But what if we paid them for this right? Hmm. The seller of that house is interested. How much will you pay them for this right?

An Introduction to Option Premium

The seller of the home agrees to the contract, as long as you pay them a premium.

Let’s say you agree on a premium of $10,000. So for the right to purchase this home between now and two years from now at $200,000, you must pay the seller of that home $10,000 today. Let’s add that to our trade details.

Strike Price: $200,000

Option Expiration: 2 Years From Today

Option Premium: $10,000

So let’s say one year has passed, and that home is currently valued at $350,000.

Wow! That’s a huge surge in price. So what does that mean for us?

Well, we bought a “call” option at the $200,000 strike price for $10,000. This means that if the value of the home rises above $200,000 plus the premium we paid, we will “breakeven” on the trade. Our breakeven price is thus $210,000.

But that house is valued at $350,000 today! Are we going to exercise our contract, and purchase the home at $200,000? You betcha!

How much did owning this call option make us?

Since we breakeven at $210,000 (strike price + premium) and the value of the home is $350,000 one year into the contract, we would make $140,000 on the trade today.

How do we do this? By “exercising” our $200,000 strike price call option and purchasing the house.

That would indeed be an amazing trade. But what if things didn’t go our way? What if, in two years, the value of that home went down in value?

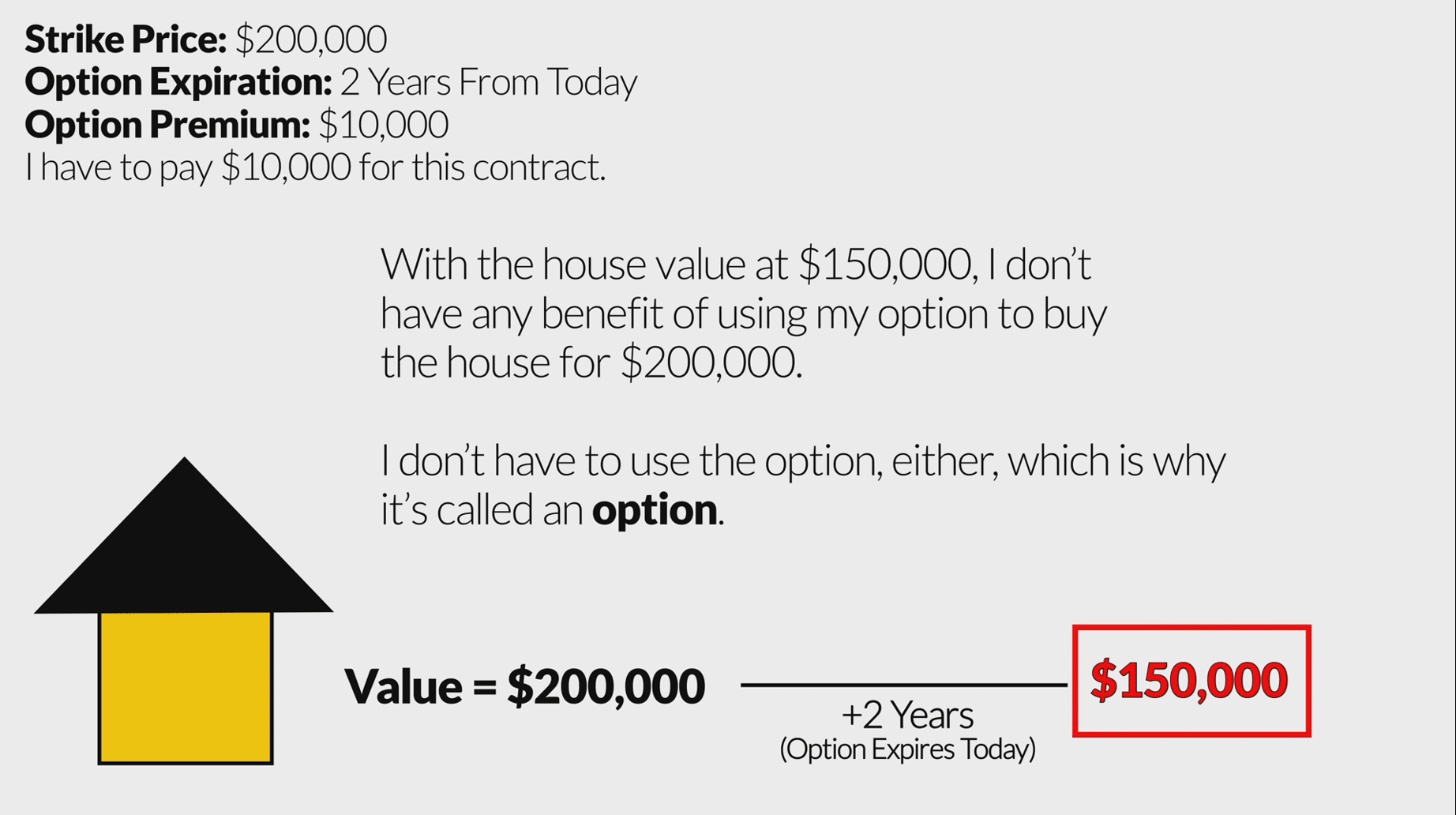

Call Options Simplified Example #2: Buying A House

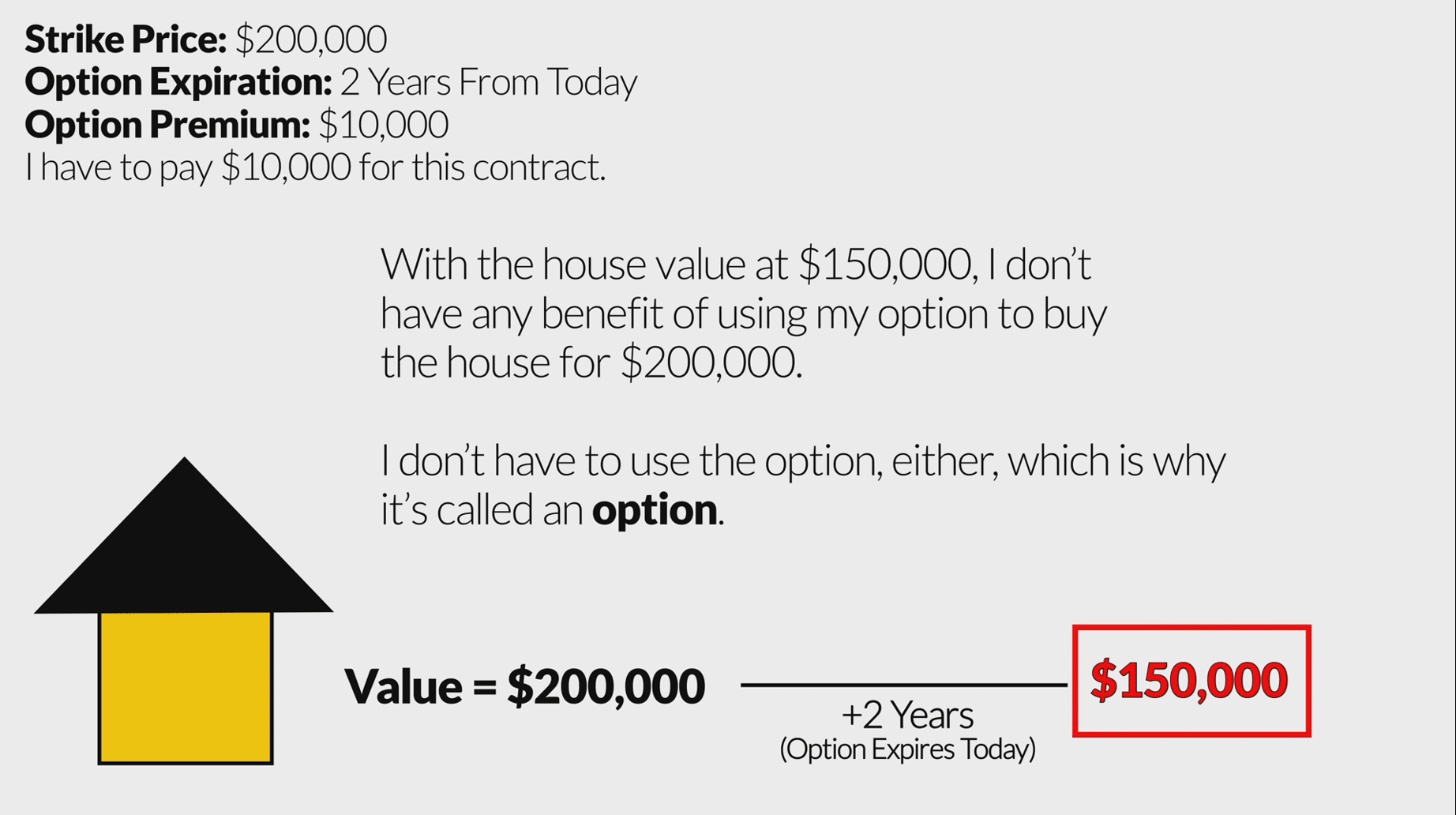

Let’s look at the same trade with a different outcome. Again, here are the details of our trade:

Strike Price: $200,000

Option Expiration: 2 Years From Today

Option Premium: $10,000

Let’s say that in this scenario, the value of the home decreased in value from $200,000 to $150,000 in the days leading up to the expiration of our 2-year contract.

This trade has gone against us. How much did we lose?

They are called “options” for a reason. We don’t have to exercise our right to buy this home – it is our option. And we paid dearly for this right, $10,000 to be exact. In order to understand our max loss in this outcome, take a moment to study the below visual.

So are you going to exercise your right to purchase this home for $200,000 when it’s valued at $150,000? No thanks.

But we are going to lose something here, and that something is the premium we paid, or $10,000.

What is the value of our call option at this moment? Well, zero.

Remember, two years have passed and that option is expiring presently. The value of that home has a 0% chance of rising to $200,000.

If you wanted to sell the option to purchase this home at $200,000, nobody would be willing to buy it. The call will “expire worthless”, perhaps the two most dreaded words for those who purchase option contracts.

Call Option vs Buying the Home in the Open Market

So we lost $10,000, and that sucks. But what would we have lost if we simply purchased the home in the first place? We would have paid $200,000 cash for it. When the value of the home fell to $150,000, we would have lost $50,000.

Now that $10,000 loss doesn’t sound too bad, does it?

This is used simply as an example. In the real world, most option premium buyers lose money. Why? Because prices typically don’t rise as fast as they did in our example. Additionally, if you had simply bought the home in the first place, you probably wouldn’t have sold that home when it was valued at $150,000. You would have waited for a bullish housing market.

With options, you don’t have the luxury of time. Options expire. Every single one of them, at some date in the future. Don’t think that simply buying call options will make you money. The vast majority of “premium buyers” lose money over time.

Now that we understand the fundamental of call options, let’s take a look at a real-world example of a call option on Tesla (TSLA) stock.

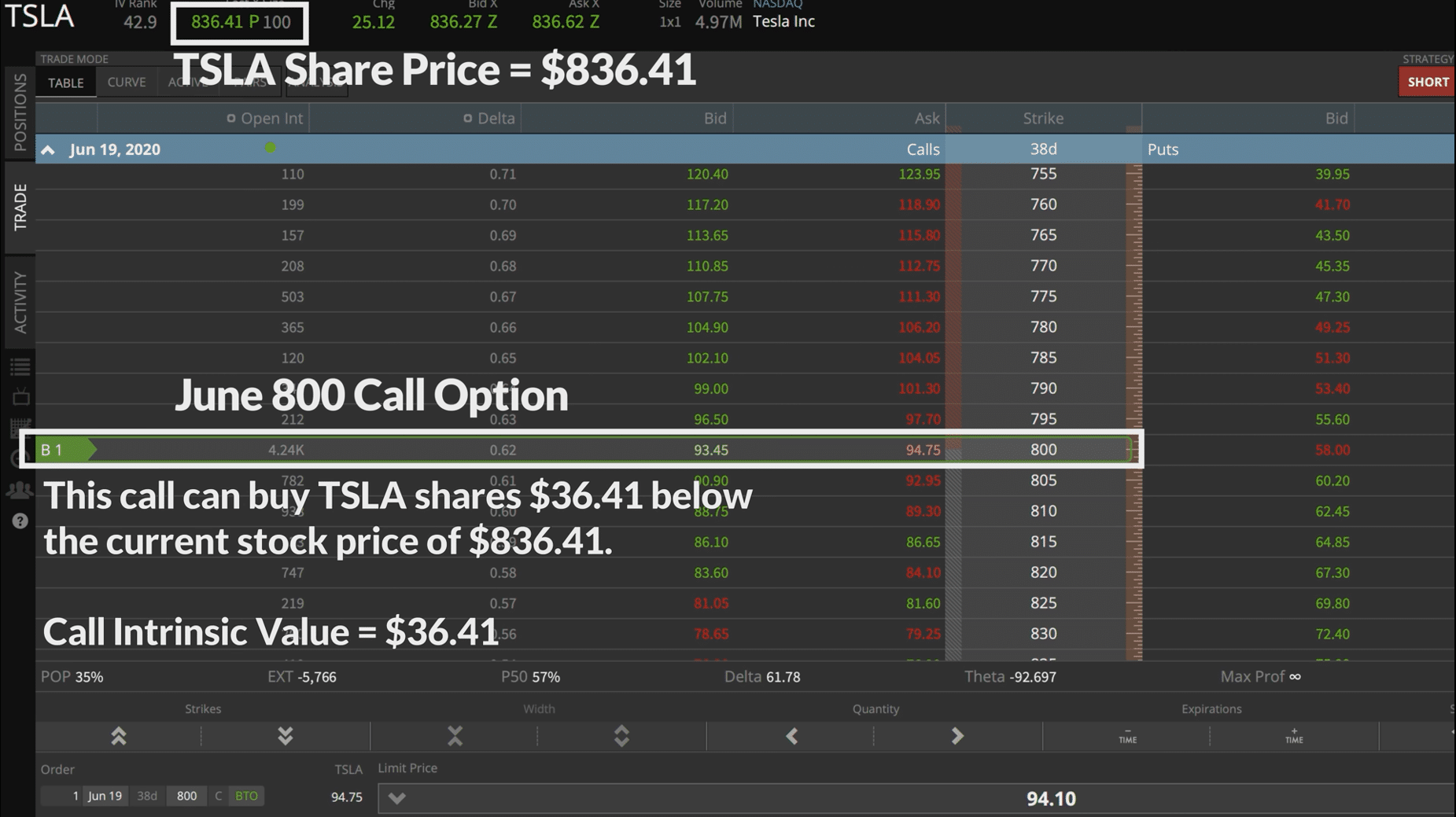

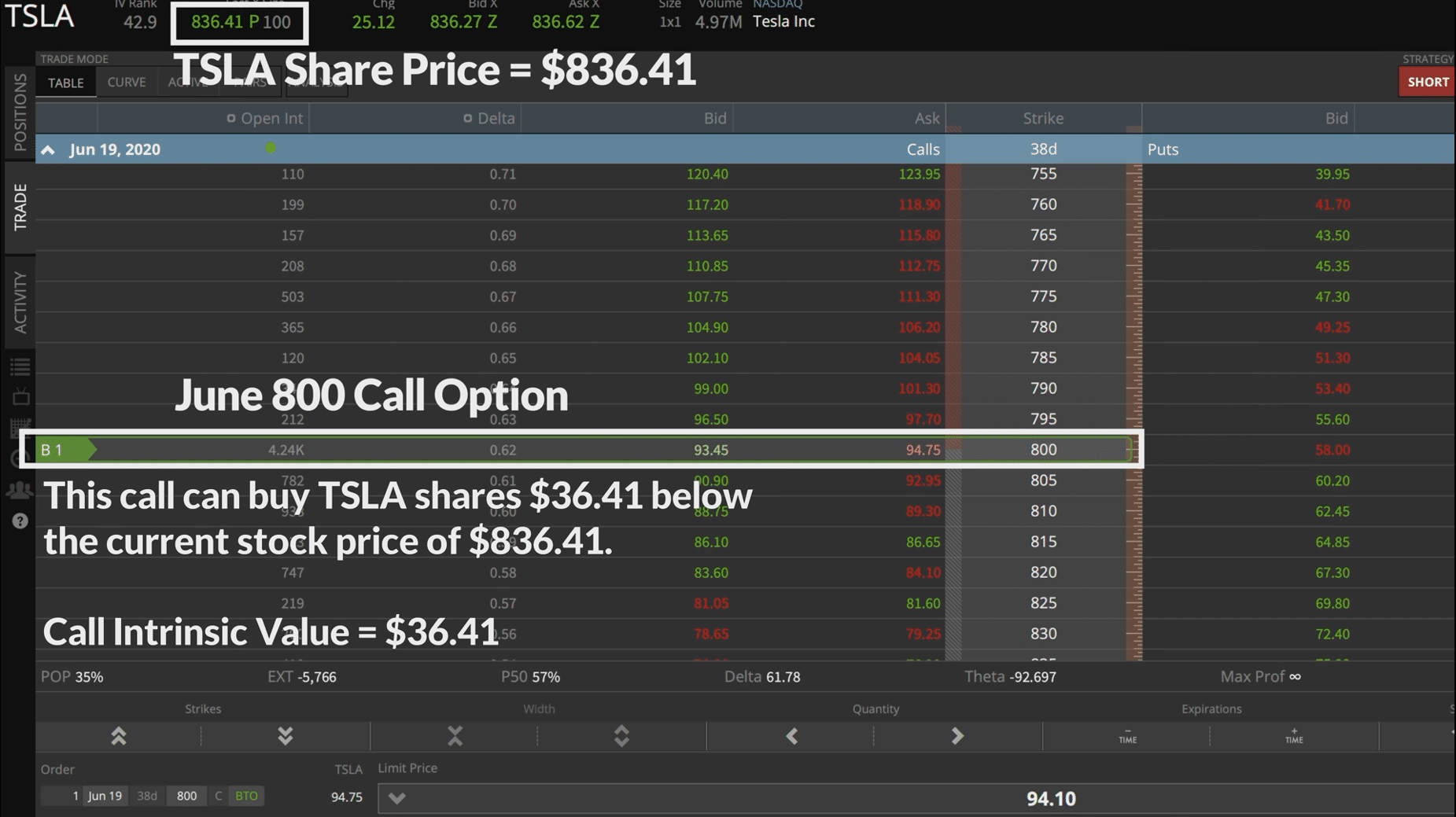

Tesla (TSLA) Call Option Example

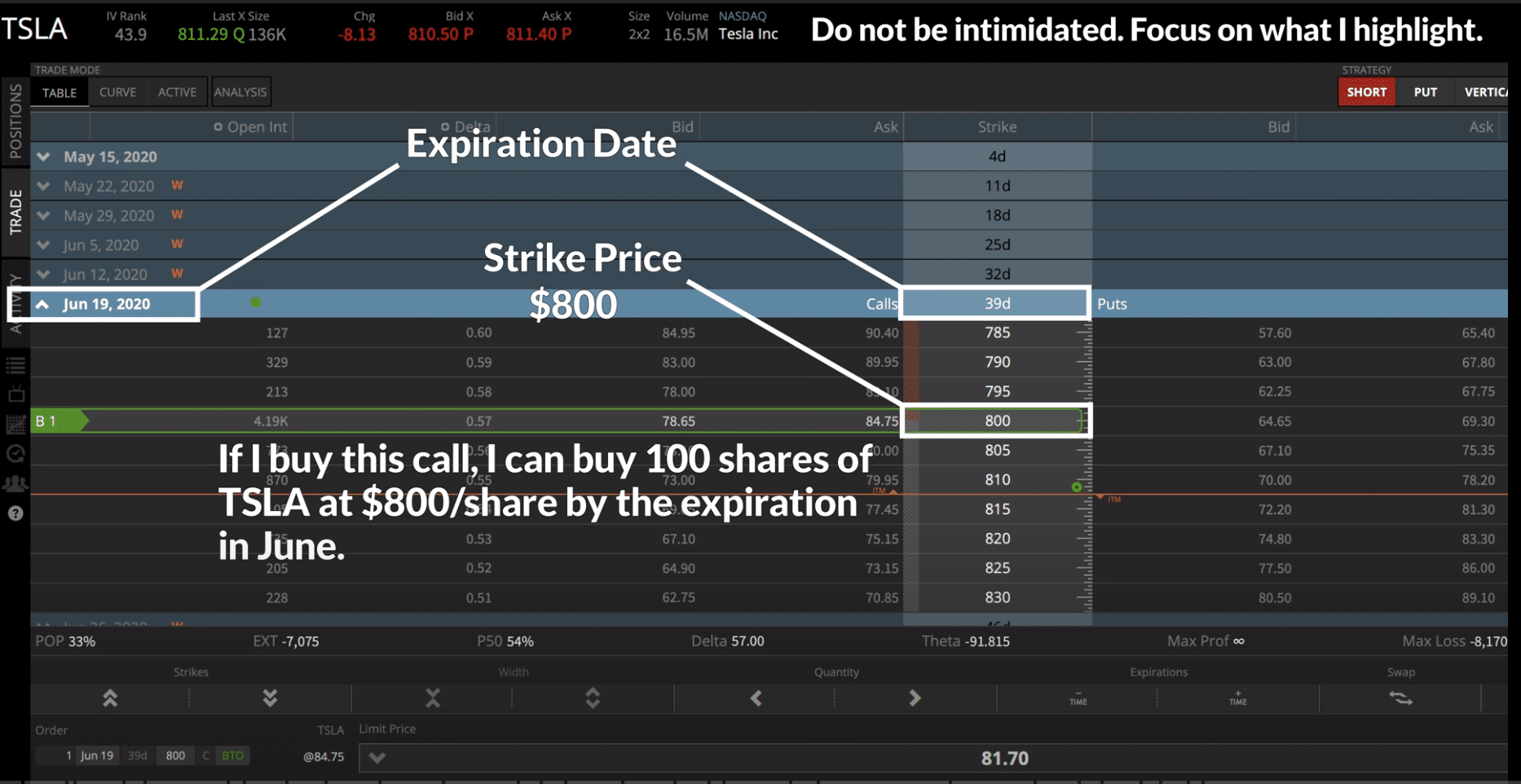

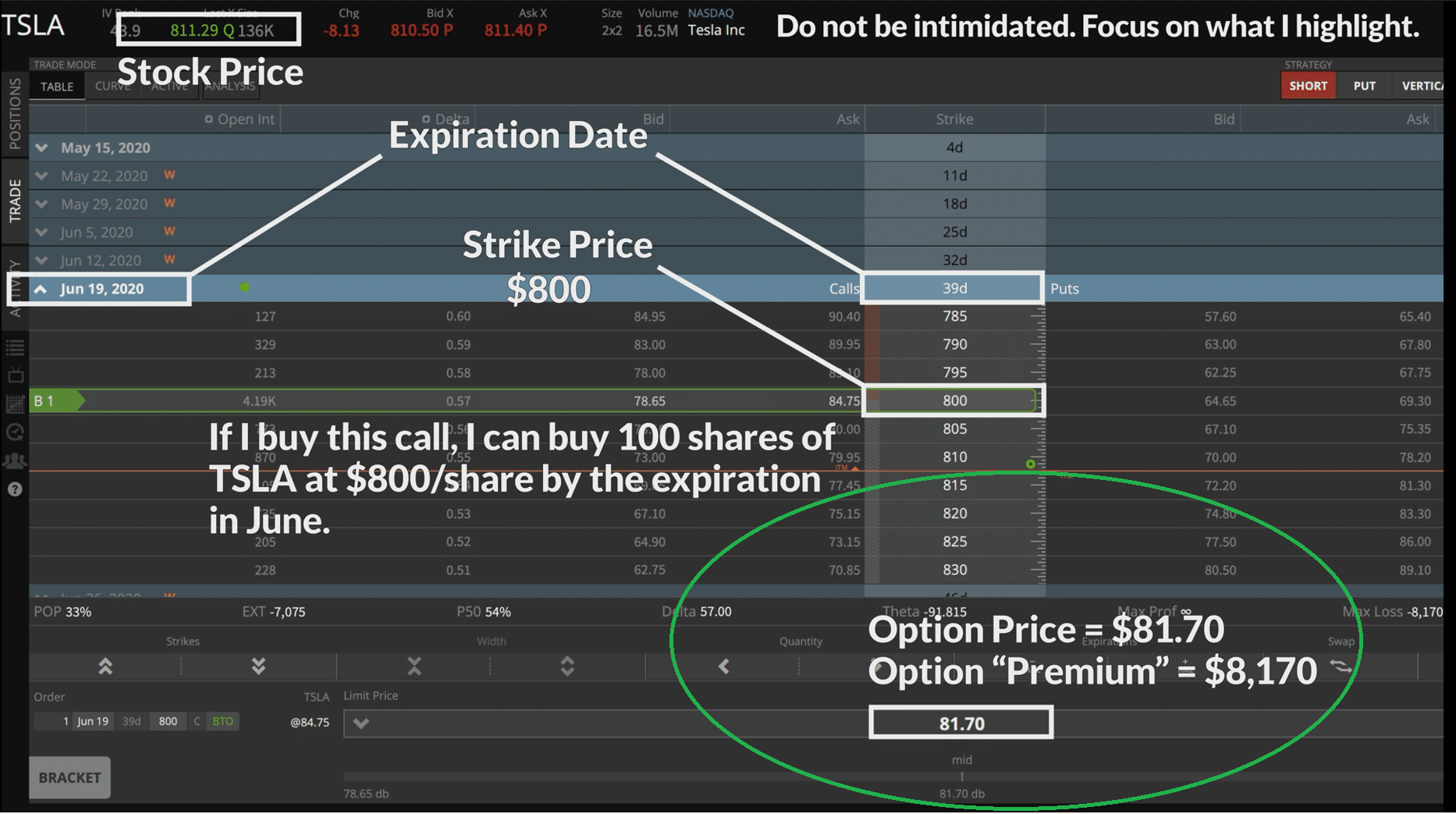

The below image (as all of our trading software images) comes from the tastyworks trading platform.

The above image highlights the various option chains on TSLA stock. We selected an option expiring on June 19th, 2020, which expires in 39 days. Additionally, we can see that we have a strike price of 800.

Also, note that the stock is currently trading at $811. That is very important.

Don’t be intimidated by the extra numbers here; remember, we know what both expiration date and strike price means. That’s all you’re seeing on this screenshot; just a whole lot of different contracts on that same “house”, which is now TSLA stock.

So what does this image tell us? If we buy the TSLA 800 strike price call expiring on June 19th, 2020 (39 days away) we will have the right to purchase TSLA stock at any point in time between now and that option’s expiration date for a price of $800 per share.

What we’re going to add here, when compared to the home buying example, is a “multiplier”.

Options Contract Multiplier Explained

When we purchased our house, our multiplier was 1. Our contract represented one house.

That is going to change here. Our TSLA call option does not represent one share of TSLA, it represents 100 shares. We touched upon this before.

Because of this, we must multiply the options price by 100 to get the true cost of the premium.

We can see that the bid for this option is 78.65 and the ask is 84.75. So what can we purchase this option for? Somewhere between these two prices. This is known as the “Mid” point (the “middle” of the bid and ask), and you can see it at the bottom of the screen: $81.70.

So buying this option would cost us $81.70. But what is our true cost, or premium? Simply multiply this number by 100:

- Option Price: $81.70

- Option Premium: $8,170

This is therefore a very expensive option. Not all options are this expensive. But why is this one so expensive?

TSLA Call Option Pricing Explained

Remember, the owner of a call option can exercise their right to purchase 100 shares of the underlying stock at the strike price specified in the contract.

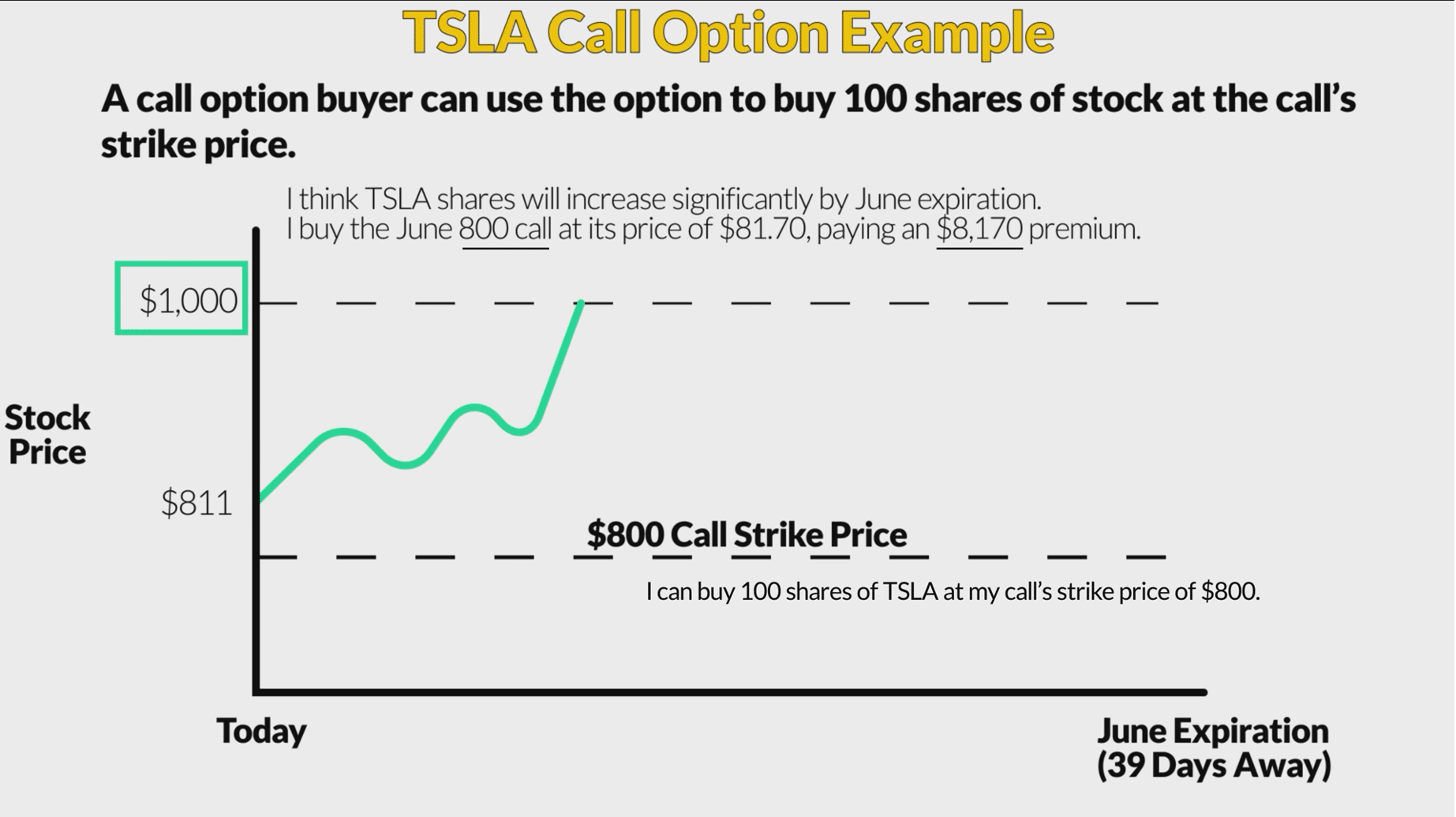

If you purchase this TSLA June 800 call option, you believe TSLA will increase in value dramatically.

Below you will find a visual of our trade in addition to the “trade details”.

Current Stock Price: $811

Strike Price: 800

Option Expiration: June (39 days away)

Option Premium: $81.70

So we bought the 800 strike price call option for $81.70.

Let’s say that in two weeks from now, TSLA has had a massive rally. The shares rallied from $811/share (the share price when we bought the call) to the share’s current price of $1,000/share.

We have in our possession a financial contract that gives us the right (but not the obligation) to purchase 100 shares of TSLA at $800/share (our strike price).

Are we going to exercise this right? You betcha!

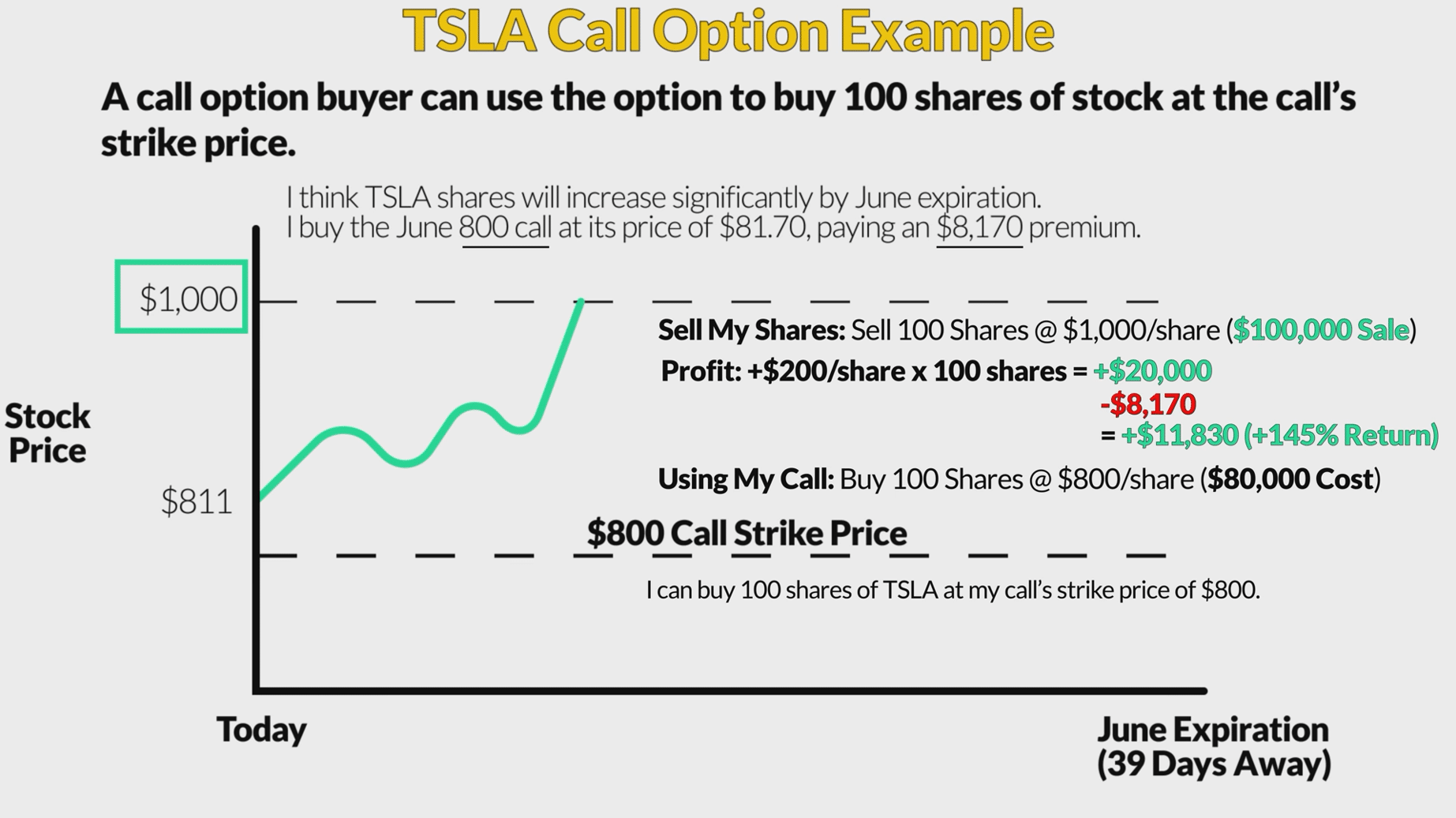

Let’s say we just exercised our option and purchased 100 shares of TSLA at $800/share.

What happens now?

Since we are exercising our right to change the option into long stock, we have to now pay for the stock. Since we are buying 100 shares of the stock at our strike price of $800, this will cost us $80,000, as seen in the chart above.

Remember, TSLA shares are currently trading for $1,000/share. We just bought 100 shares at $800/share. If we immediately sell these shares in the market we will have netted a profit of $200/share. Since we own 100 shares that profit will be $200 x 100, or $20,000.

Remember! Just like in the house example, we paid for this right. How much? $81.70, or $8,170 in out-of-pocket premium. Because of this, our profit just went down. By how much? Simply subtract $8,170 from $20,000 to get our net profit, which is $11,830 in profit, or a 145% return.

Why Tesla (TSLA) Premiums Are So Lofty

So why are the premiums in TSLA options so lofty when compared to other stocks of a comparable value?

Because TSLA stock has huge swings. It is very volatile. It may go up 25% in a month, just as easily as it may go down 30%. Option premiums take into account these swings.

If the historical price of that house we were looking at earlier only deviated between 190k and 210k, wouldn’t the call option we purchased on that home be cheaper?

The greater the odds a stock has of breaching our strike price, the greater the premium will be for options on that stock.

Before we move on to a few more interesting examples, let’s first answer one question that almost all new options traders have.

Do You Have to Exercise an Option to Make a Profit?

No! Option traders rarely, if ever, exercise their options contracts. You do not have to exercise your option to realize a profit.

So what do you do? Sell the contract in the open market, just like you did when you originally purchased the contract. Just like you would with stock.

So why are we using exercisement in our above example?

You must first understand the mechanics of options trading.

In theory, you could exercise your call option here, but in reality, traders rarely (if ever) do it. But understanding the exercise (and subsequent “assignment”) process is integral to understanding how options work. You must understand that an option’s value comes from its ability to trade like shares of stock at the strike price rather than the stock’s current market price.

In our above example, we showed how exercising our option would allow us to purchase TSLA at $800/share and immediately sell that stock at $2,000. Remembering that, let’s move onto something very important: the options pricing law.

Option Pricing Law

An option’s price will ALWAYS include the benefit (profit) that it will provide the owner if they were to exercise the option.

In other words, when we sell that TSLA call option in the open market, its extra value will be embedded in the price. Therefore, there is no need to exercise our right to purchase the underlying stock.

Let’s take a look at the details of our trade to better understand this:

TSLA Call Strike Price: $800

TSLA Stock Price: $1,000

Since we can make $200 from exercising our call, that call option must have that extra value included in its price. That extra value can be seen in the options premium, which must equal that $20,000 profit we would receive should we exercise our call.

Therefore, our call options must be worth at least $200. If the option price is $200, then the premium of that option must be $20,000.

When we look at this from a wide view, we can see this is similar to trading stock. We want to buy the option low, then sell it high. On a very elementary level when comparing stock trading with options trading, the only difference is you need to change the multiplier.

Let’s now return to our TSLA call and see what became of it after some time.

What Happened to Our TSLA Call?

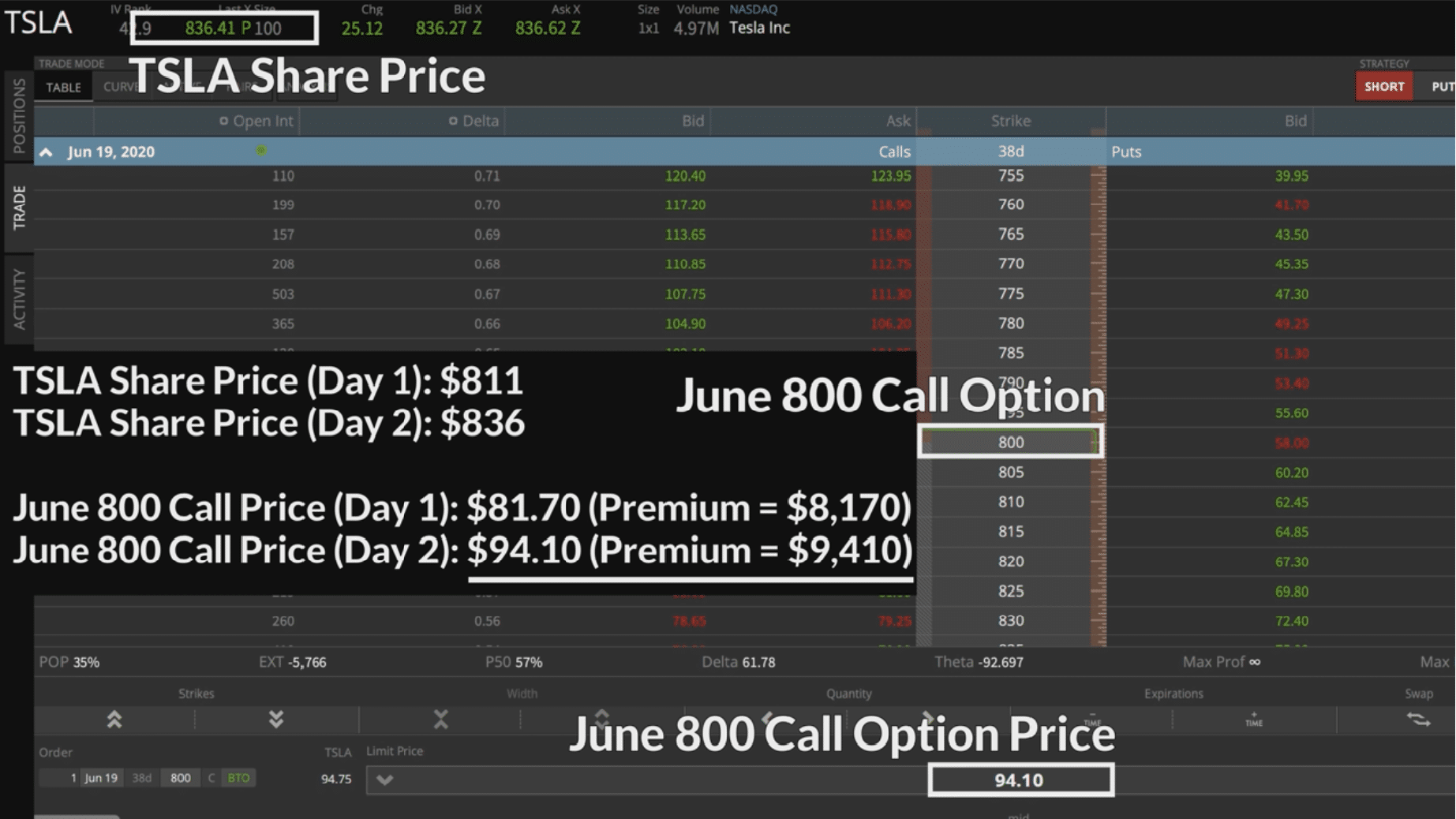

So let’s say one day has passed since we bought that TSLA call for a price of $81.70.

As it turns out, the stock has increased from $811/share to $836/share. Since the stock went up by quite a bit in a short amount of time, can you guess what happened to our call option?

Bingo! It went up in value.

We can see from the above image that the premium of that call option we purchased (or went “long”) increased in value from $81.70 to $94.10. Nice!

So how much did we make on this trade? We simply subtract 94.10 from 81.70, which gives us a profit of 12.40.

So what’s our net profit? Simply moving that decimal place over two places gives us a net profit of $1,240.

This gives us a percentage profit of 15%. Remember, this was during a time when the stock only increased 3% in value. If we would have held the stock only, we would have made much less on a percentage basis than owning the call option.

Options Give Traders Leverage

The reason that our call option was able to make 5x more returns than the stock during the same time frame is because of the great leverage that options provide. Remember, one option contract represents 100 shares of stock.

It isn’t uncommon for an option to increase 100%, even 300%, over a time period when the stock only moves 5%.

On the flip side, you will see your profits decline just as fast when the markets turn against you.

However, when you purchase an option, you can only ever lose the premium you paid: you can only ever lose 100%, but you can also make 300%, or even higher.

Recap: What We've Learned About Call Options

Let’s do a brief recap of what we’ve gone over so far.

- Call options represent one of two types of options (“put options” are next!).

- A call option gives the buyer the ability to buy 100 shares of stock at the call’s strike price.

- A call option becomes more valuable as the share price increases.

- You do not have to exercise a call option to realize profits.

- Options provide for leveraged return (and losses!).

So far, we’ve looked at the sunny side of options. But there is also a dark side. In fact, most “premium buyers” lose money over time. Let’s next look at how a call option can lose money.

How Long Call Options Lose Money

When you buy a call option, you must be right about the direction of the underlying stock price. The stock must go up in value, and go up quite fast. If the stock stays the same or goes down, you will lose money. That means, in theory, you will only make money 33.33% of the time.

Let’s revisit our house example to understand how a call option can lose money over time.

In our house example, we bought a call option with a strike price of $200,000 for a premium of $10,000.

In the second outcome (seen in the above image) the house value declined in value from $200,000 to $150,000. Since the valuation of the home is lower than our strike price of $200,000, the option has no benefit. We lost the entire $10,000 in premium.

If we still want to buy the house, we’ll just buy it at its current market price.

Let’s now look at a trade where a call option does not make money due to a subsequent fall in stock price.

Adobe (ADBE) Call Option Example

On the left-hand side of the below image, you will see the stock price of ADBE; on the right-hand side, you will see a chart that tracks our specific options price (you can chart specific option prices just as you can chart stocks!).

So in this example, we decided to purchase a call option on ADBE with an expiration of May 18th. Here are our trade details:

ADBE Stock Price at Entry: 362.52

Call Strike Price: 380

Days to Expiration: 12

Option Price at Entry: $1.92 ($192 Premium)

Looking at the bold line on both charts, we can see what happens to both the option and the stock as time passes and that May 18th expiration approaches.

We bought the ADBE May 18th 380 call, so we believe the price of ADBE would be above 380 by May 18th.

However, we can see that is not what happened. With only one-day left until expiration (on May 17th), the option we paid $1.92 for is only worth $0.01!

Why?

Well, the price of ADBE stock fell from $362.52 to $355, not anywhere near the price of our 380 strike price call!

What are the odds that ADBE rallies from $355/share to $380/share in one day? Not great. That is why our call option is only worth a penny. Who the heck wants to buy ADBE for $380/share when it’s trading at $355/share?

ADBE Stock Price at Entry: 362.52 ——-> $355

Call Strike Price: 380

Days to Expiration: 12 Days——-> 1 Day

Option Price at Entry: $1.92 ($192 Premium)

So what do we do now? Well, probably nothing. If/when that option closes out-of-the-money (more about option “moneyness” to come) at expiration, it will expire worthless. The next trading day, it will simply disappear from your account. No action is required. We will simply have lost the entire premium of $192 paid.

We’ll dive deeper into closing options later on, but for now, just know that as the stock price drifts further away from your strike price, your option contract will approach zero.

OK! Ready to move on to “puts”? Take a break, then let’s plow ahead!

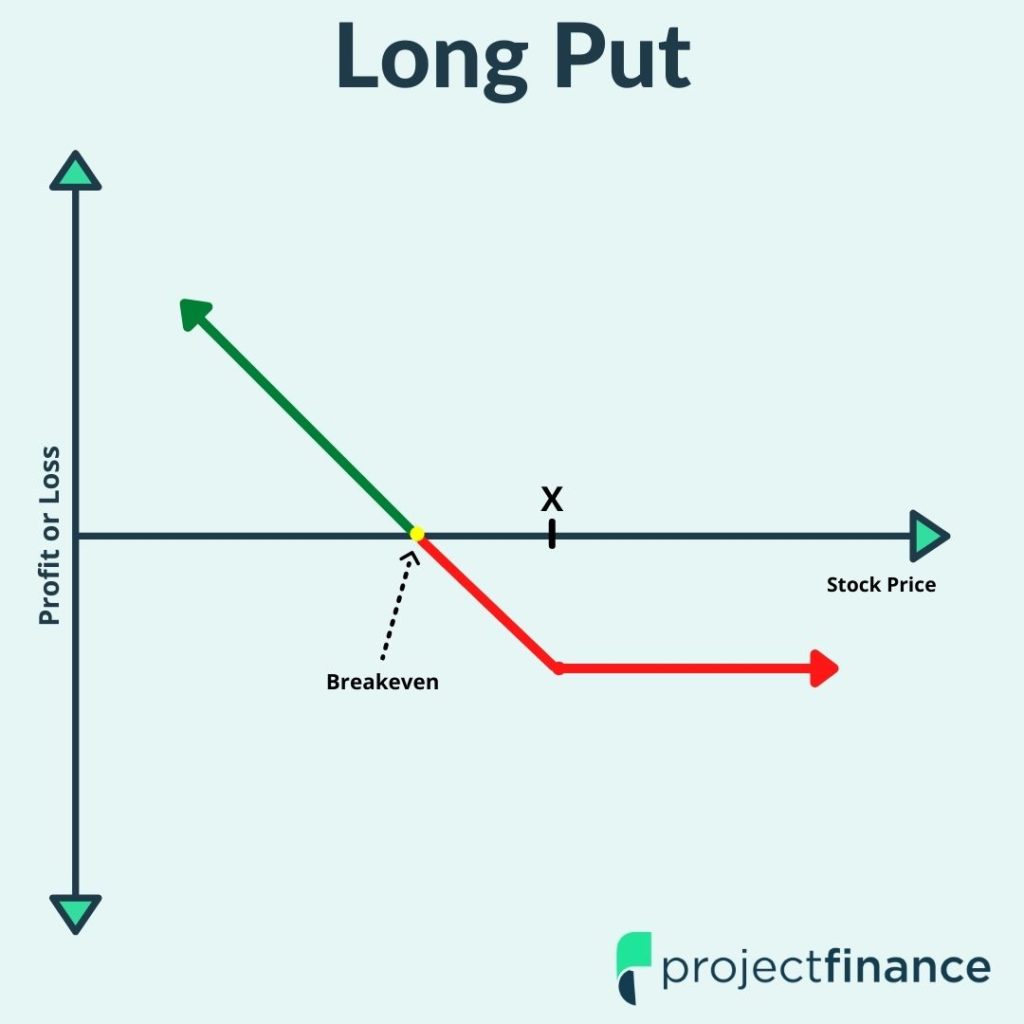

Put Option Introduction

We mentioned in the last section that all options contracts are either calls or puts. We went over call options in our last example, but what are put options?

Let’s take a look at the textbook definition, then we’ll explore what a put option really is.

Put Option Definition: A put option (put) is a financial market derivative instrument that gives the holder the right to sell a stock at a specified price, by a specified date to the seller of the put.

Ok, that probably didn’t help you much. I know it didn’t help me when I began learning this stuff 15 years ago. Let’s break it down into a few bullets.

- Broadly speaking, put options increase in price as the stock price falls. Conversely, put options decrease in price as the stock price rises.

- The core difference between call and put options is that put options give their owners the right to SELL 100 shares of stock at a specified strike price by a specified date. With call options, we had the right to BUY 100 shares of stock. We are just going from buying to selling.

- Put options are essentially the evil twins of call options in that their profit/loss profiles are the exact opposite of call options. Take everything we just learned about call options, then flip that knowledge on its head, and you’ll understand put options.

So since put options give us the right to sell a stock, doesn’t it make sense that the value of a put option increases as the stock price falls?

Let’s look at an example.

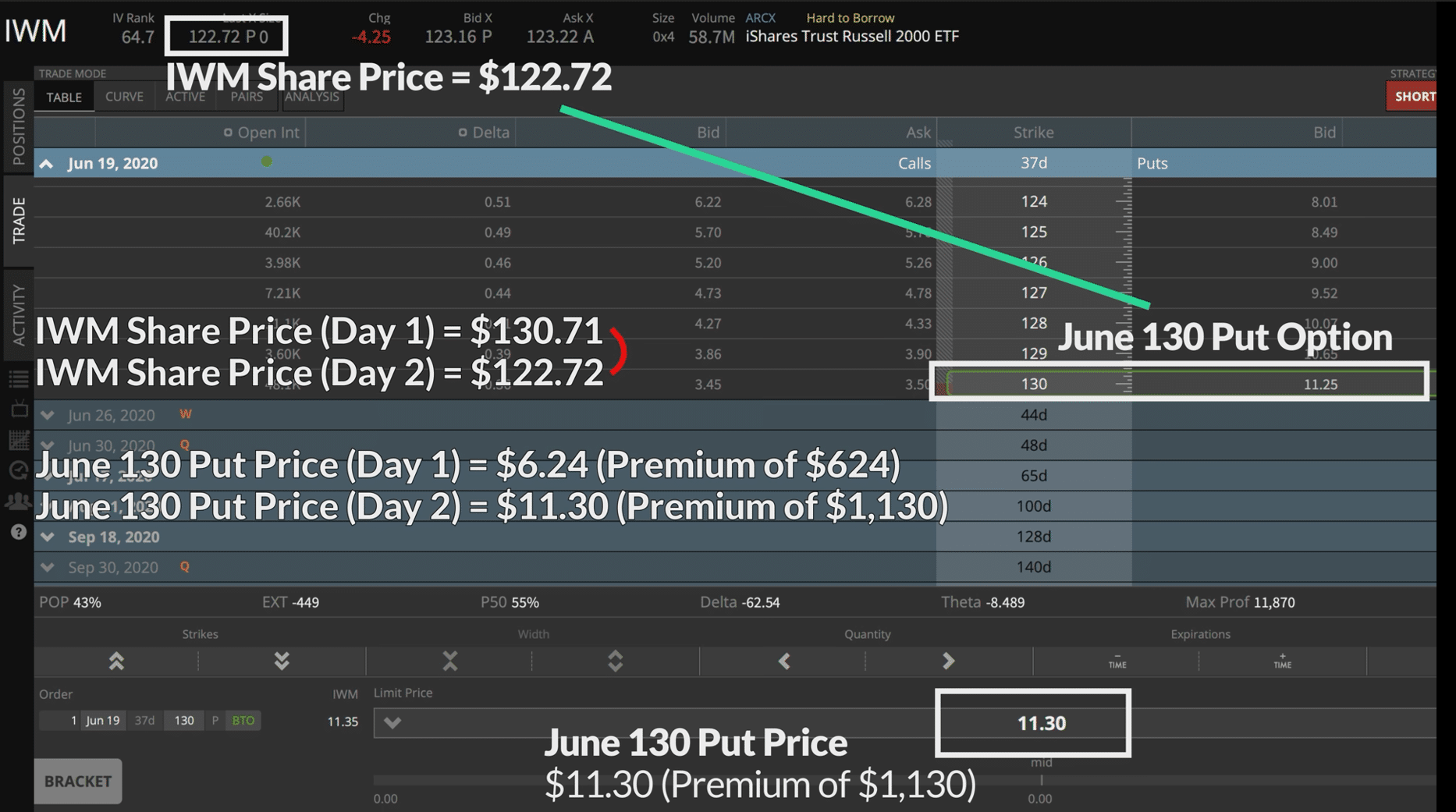

IWM Put Option Example

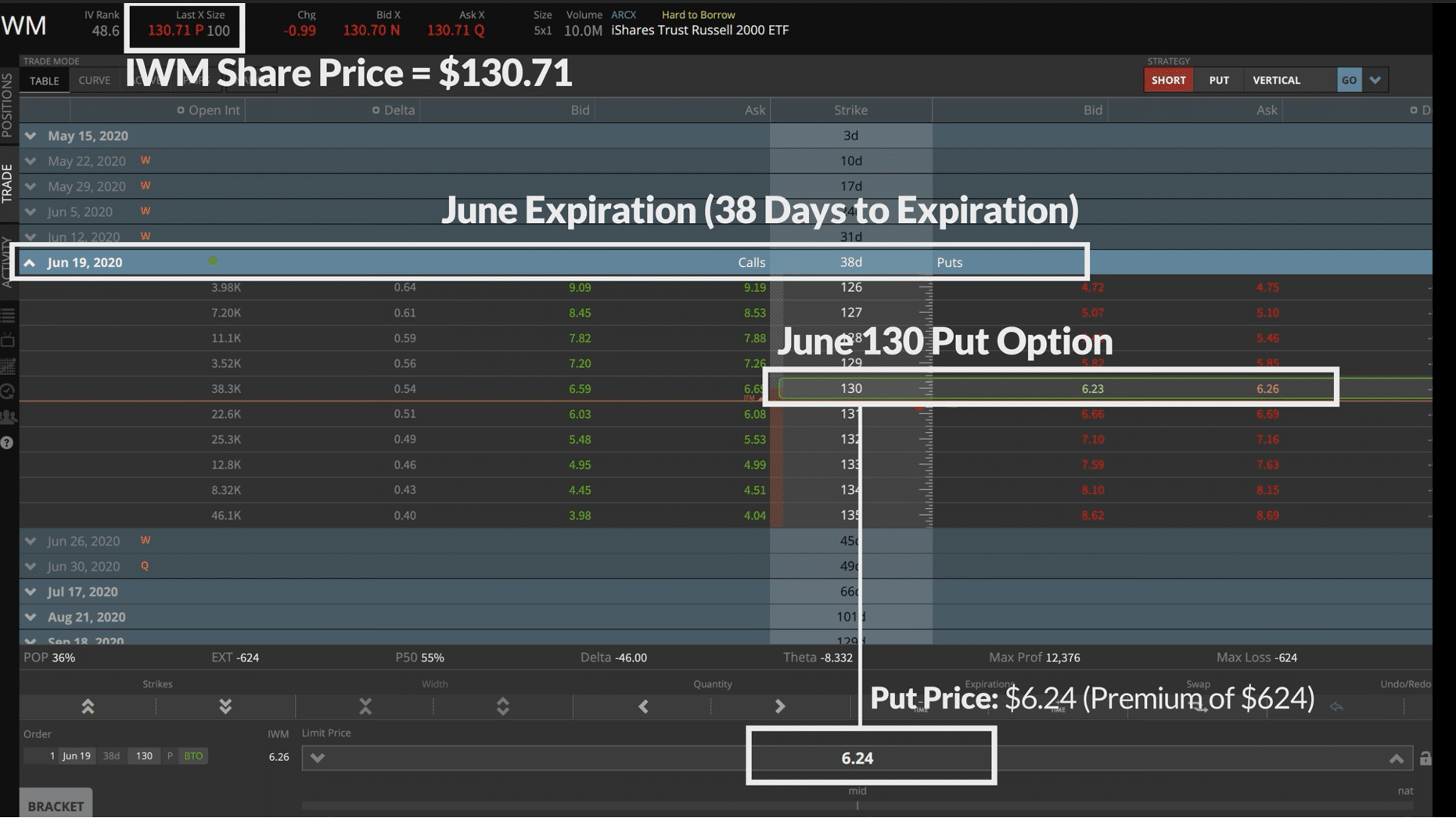

The below screenshot (taken from the tastyworks trading platform) shows us the options chain for IWM, which is an exchange-traded fund (ETF) by iShares that tracks the Russell 2000 ETF.

Here are the initial details of our trade.

IWM Share Price: $130.71

Expiration: June (38 Days Away)

Strike: 130 Put

Option Price: $6.24 ($624 Premium)

Just to reiterate, the mechanics here are all the same as those of call options.

- Our maximum loss is still the premium paid ($624).

- Our multiplier is still 100.

- We are making a very directional bet (bearish instead of bullish now)

The only difference is here, we believe the stock is going to go DOWN in value as opposed to up.

So we are long the 130 put when the stock is trading at $130.71. This means we believe the stock is going to go down in value. By how much? Well, at least to $130/share.

But even if the stock is at $130/share at option expiration, we still won’t make money. Why? Just like with calls, the stock has to move far enough to cover the premium paid.

In this example, we paid $6.24 for the call. So, the stock must fall to $123.76 before we start making money. How did I come to this number? Simply subtract the premium (6.24) from the strike price (130).

Now let’s take a look at how this trade plays out.

IWM Put Option Trade Outcome

Here’s a visual of how our trade played out after only 1 day.

IWM Share Price: $130.71 —–>$122.72

Expiration: June (38 Days Away)

Strike: 130 Put

Option Price: $6.24 ($624 Premium) —-> $11.30 ($1,130 Premium)

So what happened here? The stock went down in value. If we had a call, we would be shaking our heads; but since we own a put, we are celebrating.

The stock has gone down in value by about $8/share. Since our put option gives us the right to sell 100 shares of stock at the strike price 130/share, our put options value has gone up. Wouldn’t you rather sell stock at $130 as opposed to $122.72, the current stock price?

Short selling can be confusing, but for now, just know that when you sell something, you want it to go down in value to buy it back cheaper.

In theory, you can sell 100 shares of this stock right now for $130/share, then immediately buy it back for $122.72/share, netting us a profit of $7.28/share. Remembering that a put option represents 100 shares of stock, this gives us a profit of $728 (not considering the premium paid).

However, as we learned before, exercising your options is NOT the best way to realize your profit. You will actually lose money by exercising your option (more on this later) as opposed to outright selling the option in the open market.

Right now, we can sell that option for $11.30. Since we bought it for $6.24, that gives us a net profit of $5.06, or $506.

Profitability of Shorting Stock vs Owning a Put

Our put netted us a profit of +81%. During this same time, the stock only fell by -6.1%. How is this possible?

Just as we talked about with calls, this is because of the great leverage that options offer us. On the other hand, we can equally lose money just as fast when the underlying stock goes against us.

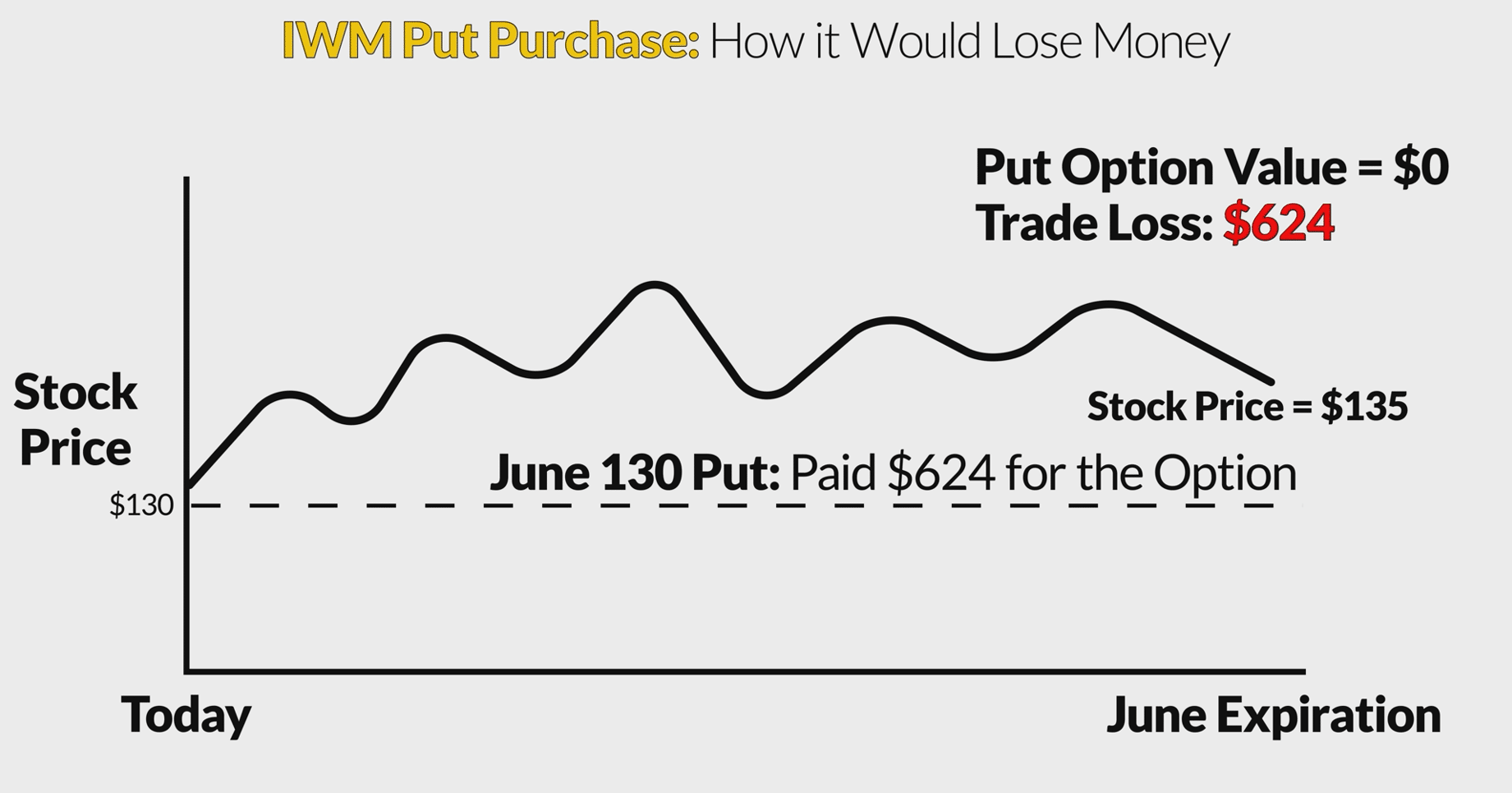

Losing Money Buying Puts

So what would happen to the profit/loss on our put option if the price of IWM went up instead of down?

In the above trade example, we looked at the profitability after one day. Let’s fast forward now to expiration and see how our put performed.

In this example, IWM closes above our strike price of 130 at expiration. This is not good news for our put.

How much did we lose? The entire premium of $624 paid. Who in the world would want to sell stock at $130/share when that stock is trading at $135/share on expiration? Nobody. Therefore, we will lose it all.

Let’s take a look at another put example now on Nvidia (NVDA)

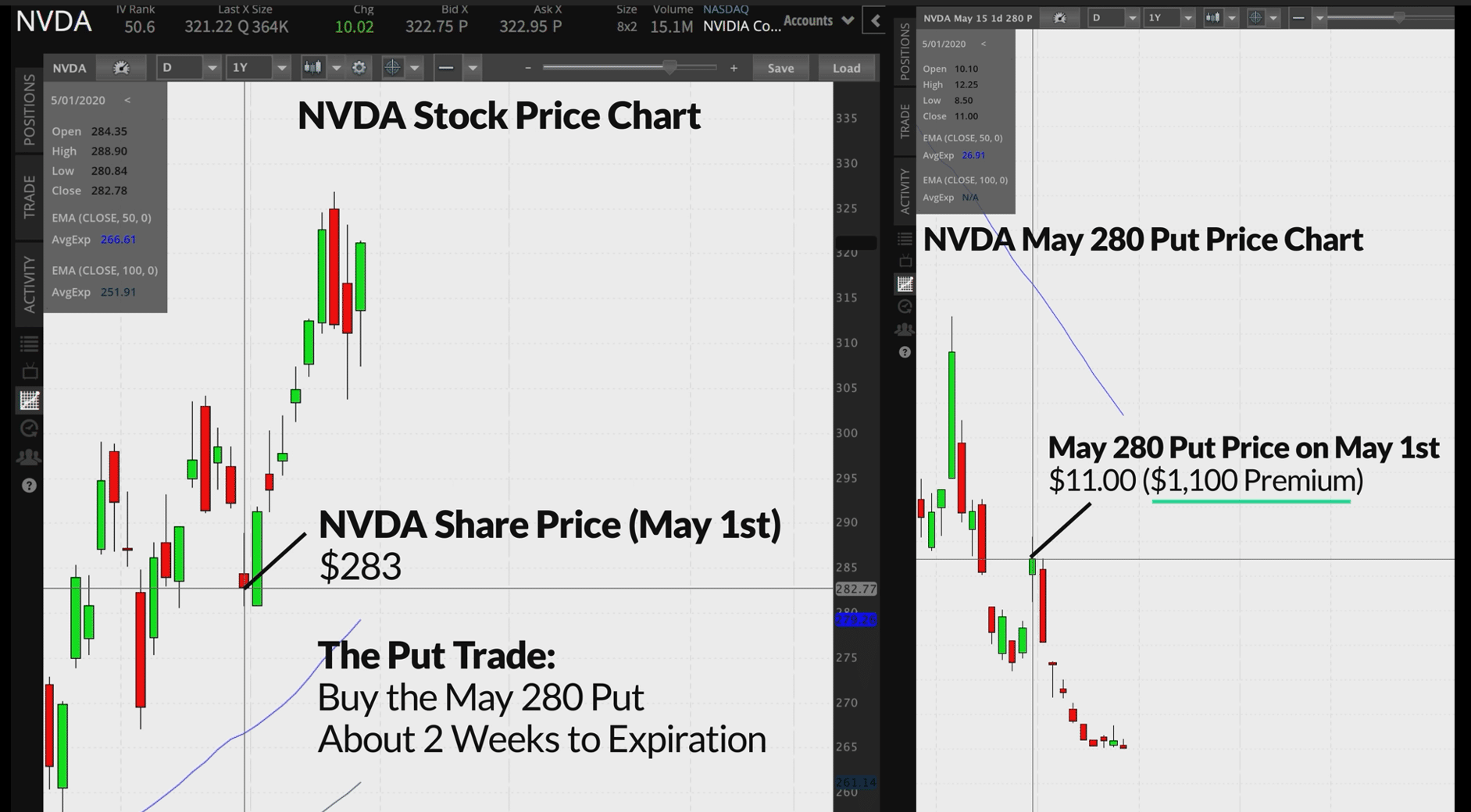

Nvidia (NVDA) Put Option Example

The below image shows two charts on NVDA; on the left-hand side, we see a stock chart of NVDA; on the right-hand side, we see a chart of our put option on NVDA. Note the upward trending stock price; that is not good news for a long out.

And here are our initial trade details:

Initial NVDA Share Price: $283

Expiration: May 18th

Strike: 280 Put

Option Price: $11 ($1,000 Premium)

So we can see that after we bought our put, the stock surged higher. How did our long put fare? Not well!

As expiration nears, the price of NVDA skyrockets from $283/share to $321/share. Our put option gives us the right to sell 100 shares of NVDA at $280/share. As the stock trends higher and expiration nears, that put options approaches 0 in value. Ouch!

Initial NVDA Share Price: $283 —-> $321

Expiration: May 18th

Strike: 280 Put

Option Price: $11 ($1,000 Premium) —->$0.00

So what will happen if our put option is out of the money at expiration? It will expire worthless and disappear from your account. No action is required on your end. Even if you wanted to sell it, you probably wouldn’t be able to. Why?

Well, would you pay for the right to sell stock at $280/share when it’s trading at $321? Nobody else is willing to pay either.

This is an example of the downside of leverage; you can lose it all just as fast as you can triple your initial investment.

This leads us to another interesting subject.

Buying Puts vs. Shorting Stock

Put buying does offer investors an additional benefit when compared to selling short stock, and that involves risk.

Given the amount of leverage that options offer, this may come off as counterintuitive, but options actually offer less risk than selling short stock.

Why? When you sell short a share of Apple (AAPL), what is your maximum loss? In theory, it is infinite. There is no cap on how high AAPL can run.

If you were alive in 2021, you surely heard about the Wall Street vs Reddit GameStop (GME) battle. In a matter of weeks, GME went from about $10/share to $300/share. If you were to short one share of GME at $10, your losses would be $290/share, about 30X your initial investment.

Put options, however, have defined risk: it doesn’t matter how high the stock goes, your maximum loss will ALWAYS BE the premium you paid.

However, in order to profit on a put, you need the stock to go down fast. Similar to call options (only flipped around), if the stock stays the same or goes up, you will lose money.

You may even lose money if the stock falls! How? The stock may not fall fast enough or by enough percentage to reach your long put strike price – premium paid.

For more information on shorting stock (and GME) please read our article Long vs Short Explained.

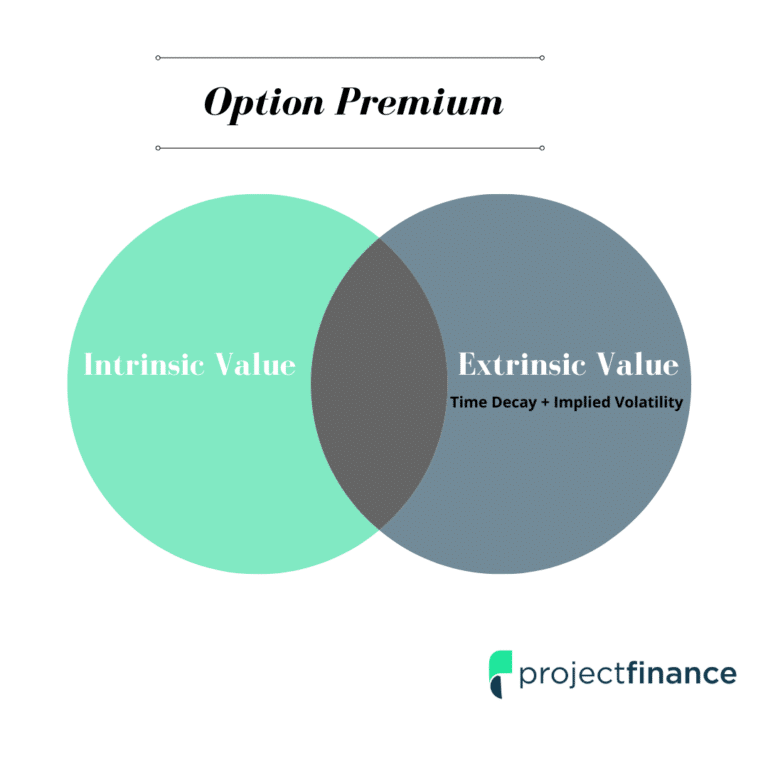

Option Price Components (Intrinsic & Extrinsic Value)

Next on our options education journey comes the price components. Let’s look at the definition, then break it down.

Option Price Components: An option’s price consists of two distinct parts: intrinsic value and extrinsic value, aka time value (theta). Intrinsic value measures an option’s profitability based on the strike price when compared to the stock’s market price. Time value (extrinsic value) refers to the portion of an option’s premium that is ascribed to the amount of time remaining until the expiration of the option contract.

So far, we have discussed the two most basic options trades that an investor can place; “long call” and “long put”. You must understand both of these thoroughly before we move on. If you don’t understand the foundational call and puts, you won’t understand the innumerable ways that you can combine them. That’s when things get interesting.

In addition to understanding calls and puts, you must also understand what intrinsic and extrinsic values are. Having a solid grasp of these terms will help you better understand more complicated options strategies, such as “iron condors” and “calendar spreads.”

So let’s get right into it.

So far, we have studied how an option contract trades as it does, but we haven’t yet understood why.

Chances are, you have been asking yourself some questions in the above examples. A lot of those questions will be answered in this segment, which will explain why an option is priced the way it is.

Two components make up the entirety of an options price.

- Intrinsic Value

- Extrinsic Value

Intrinsic Value Explained

Though you may not know it, you probably already know what intrinsic value is.

Remember that home example, when the home was valued at $350,000 and we were long the $200,000 call? Keep that in mind.

Here’s one definition of intrinsic (divorced from options): Intrinsic value is a property of anything that is valuable on its own

Keeping in mind “valuable on its own”, the intrinsic value here would be 350k-200k, or $150k. This is the amount that the option is valuable on its own, not including external factors. Therefore, the intrinsic value, or the least amount of money that we should accept for this home, is 150k.

In other words, intrinsic value is the amount an option is “in-the-money” by, more on this term later (though it’s pretty straightforward!).

So that was a call example, but what about the intrinsic value of a put?

Again, just flip everything on its head for puts. If you own a put option with a $130 strike price, and the stock price is $120, that tells us our put is in-the-money by $10. This is the least amount of money we can sell the options for. Also, (going back to our definition) you can look at that $10 portion of the options premium as the value of the option that is valuable on its own.

Intrinsic Value of Options

Let’s take a look at one more example.

TSLA Trade Details:

Call Strike Price: $800

Stock Price: $1,000

So we are long a TSLA $800 call with the stock trading at $1,000. What’s the intrinsic value of our call?

Bingo. $200. Simply subtract the stock price from the call price, and you will have your intrinsic value.

TSLA Trade Example: Introduction to Extrinsic Value

So if intrinsic value is the least amount of money we should sell an option for excluding external factors, don’t you want to know what those external factors are? Sure! We want to sell our option for as much as possible. The external factor portion of the value of an option is known as “Extrinsic Value”.

Let’s take a look at a real-world example here on Tesla (TSLA).

Call Strike Price: 800

Stock Price: $836.41

Intrinsic Value: $36.41

Current Option Price: $94

Hopefully, you were able to figure out the intrinsic value here. What should be interesting to you is the option is not valued at its intrinsic value of $36.41, but much higher, coming in at around $94.

So where does that almost $60 in extra premium come from? Extrinsic value. Remember, the value of an option is either extrinsic or intrinsic value. If it’s not one, it’s the other.

Let’s explore extrinsic value next!

Extrinsic Value Explained

An option’s extrinsic value is the portion of the option’s price that exceeds its intrinsic value. Sometimes, this value is referred to as “time value”.

Pretty simple, right? Extrinsic value is simply everything leftover from intrinsic value.

So if intrinsic value is determined by the amount an option is in-the-money by, what determines extrinsic value?

An option’s extrinsic (aka “time value”) is the portion of an option’s price associated with the potential for the option to become more valuable as expiration approaches.

Doesn’t that make sense? Over time, extrinsic value sheds as the option has less time to meet/exceed the strike price.

Let’s revisit the TSLA trade example from above.

Call Strike Price: 800

Stock Price: $836.41

Intrinsic Value: $36.41

Current Option Price: $94.10

Extrinsic/Time Value: $57.69

Time to Expiration: 38 Days

We can see that the intrinsic value of the option is $36.41. We learned that before; this is simply the amount an option contract is in-the-money by.

If this were the only factor at play, the option would be priced at $36.41. But it’s currently priced at $94.10. This price exceeds the intrinsic amount by $57.69.

Guess what that $57.69 represents? You got it. It represents the option’s extrinsic value.

So why does that extrinsic value exist?

TSLA shares are incredibly volatile. They swing all over the place.

This option currently has over 30 days to expire. During this time, there is a lot of potential for the stock price to swing higher yet.

If you’re a science buff, you could call the extrinsic value the options “potential” energy and the intrinsic value the options “kinetic” energy.

Extrinsic Value Over Time

We learned that an option’s “extrinsic value” is synonymous with an option’s “time value”. Let’s understand why.

In the above TSLA trade, the options extrinsic value was high because there were over 30 days left in the options life. That is plenty of time to send that option to the moon should investors like Elon’s next tweet.

So what happens to that options’ extrinsic value over time as expiration nears? Bingo. It goes down. That is assuming the option stays in-the-money.

When An Option is All Extrinsic Value

We mentioned earlier that intrinsic value represents the portion of an option that is inherently valuable. You can see that value. But what about options that are “out-of-the-money”, like those losing trades we covered earlier?

The value of out-of-the-money options is ALL extrinsic value. And since extrinsic value sheds as expiration approaches, guess what their extrinsic value will be at expiration if the option remains out-of-the-money? Zero. Their intrinsic value is also zero. That should explain why those options expired worthless.

Let’s now see this in action.

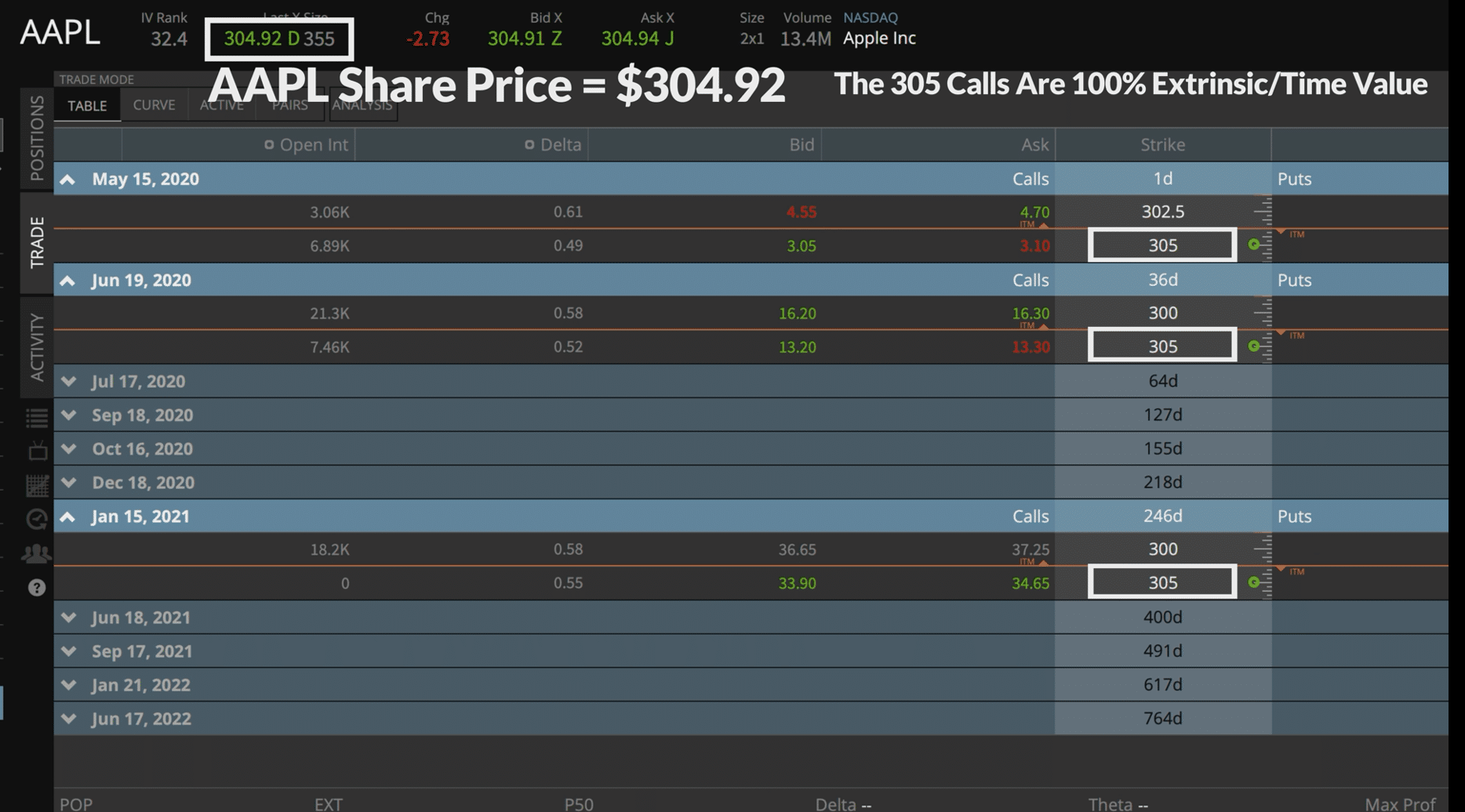

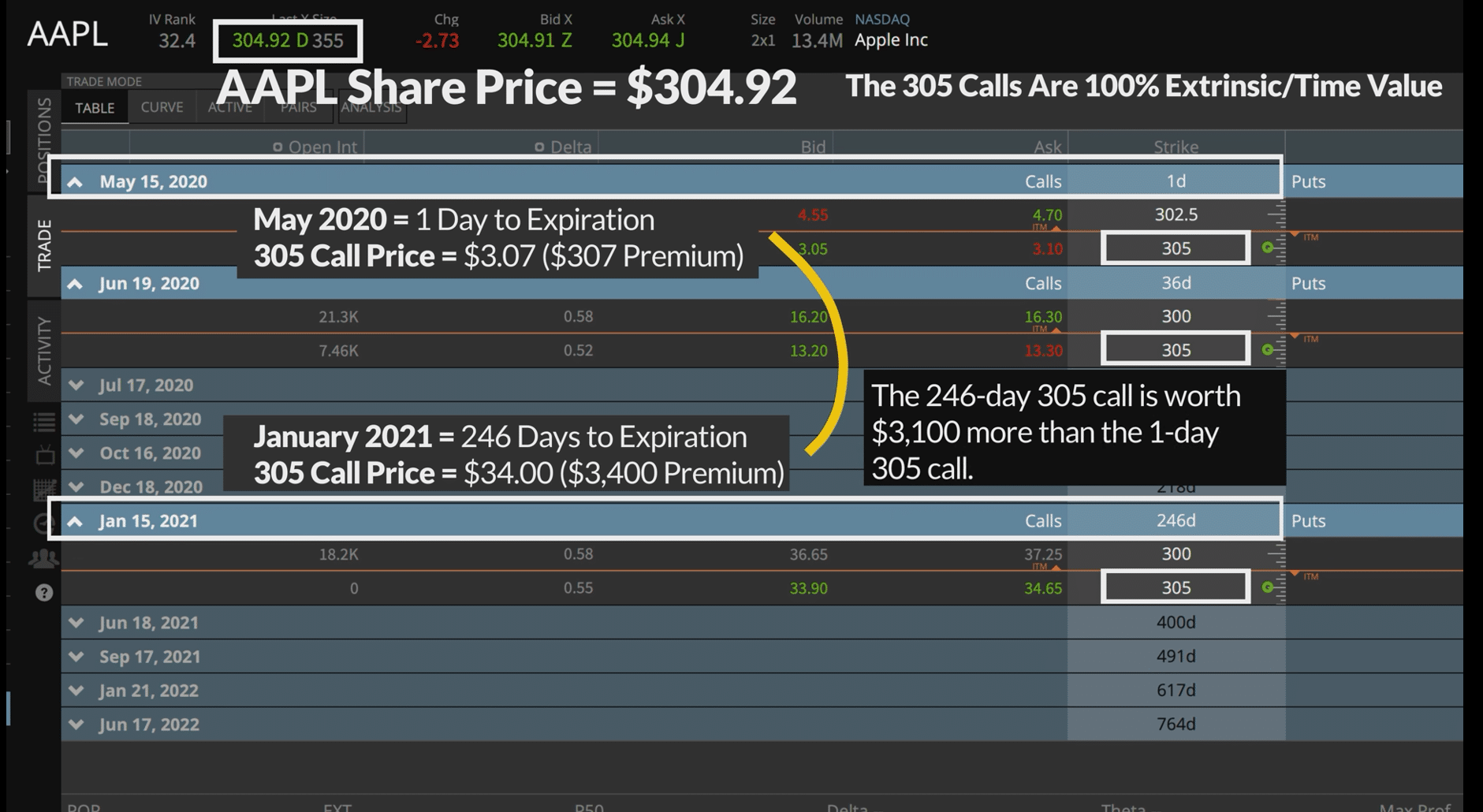

Extrinsic Value Comparison Using AAPL Options

Take a moment to study the below image.

In the above options chain, we have selected several different call options. Though their expiration dates are different, there is one constant theme: they are all out-of-the-money, meaning the strike price is above the stock price.

This means that the options have no intrinsic value. But they do have some value, and that value is extrinsic, 100% extrinsic value to be exact.

This simply means that their value is derived completely from the time value, or hope, that the stock price will rise above our 305 strike price before expiration.

Now take a look at the January 305 call options with 246 days until expiration trading at about $34. Compare that with the January 305 call option expiring in 1-day trading at about $4.60.

That’s a huge price difference! (when we say price, we also mean extrinsic value, since the option is ALL extrinsic value).

This should make sense. The January option allows for a TON more time for AAPL to breach its strike price than that of the May option, which expires tomorrow.

So let’s say we went ahead and bought that January AAPL 305 call for $34 ($3,400 premium). We’ll also assume that all of the 246 days have passed, and AAPL hasn’t budged one bit, but traded at $304.92 during the duration of the trade, all the way to expiration.

So what happens to our call option premium? In an environment where the stock price remains the same, our option is going to slowly decay, as seen above. With one day to expiration, this option will be trading at a fraction of its initial price.

We mentioned earlier that if you buy a call or put option, and the price of the stock doesn’t budge, you will lose money on that option. Hopefully, now you will understand why.

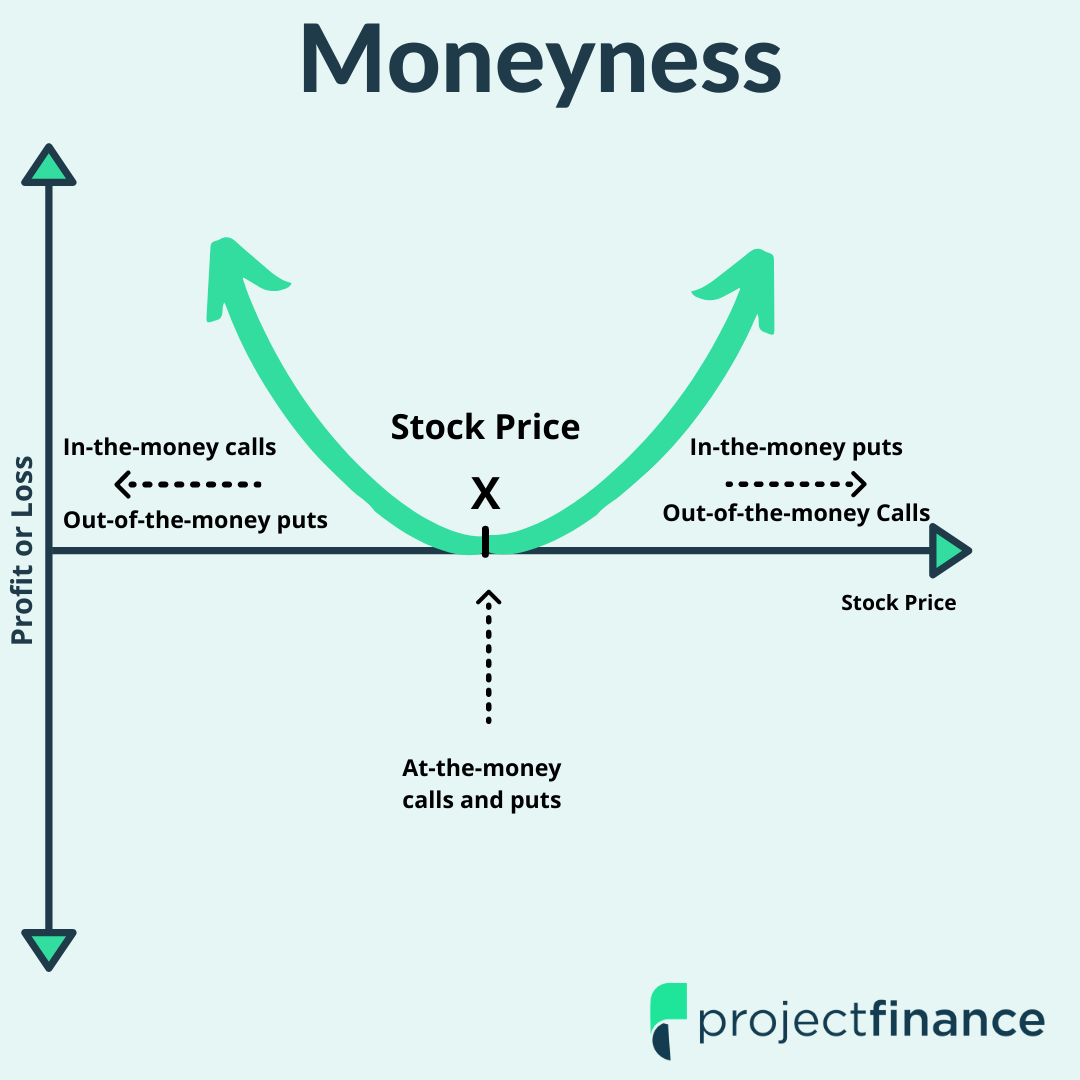

So far, we have used the terms “in-the-money”, “at-the-money” and “in-the-money”. Chances are, you have a general idea of what these terms are by now. Let’s take another look at them before we move on, as understanding them is integral to what we will learn next.

Option "Moneyness" for Beginners (ITM, OTM, & ATM)

All of the “moneyness” terms (in-the-money, out-of-the-money, & at-of-the-money) describe an options strike price relative to the stock price. Therefore, they also tell us whether an option has intrinsic value or not.

In-the-Money (ITM) Options

Any option with intrinsic value is said to be “in-the-money (ITM)”.

ITM Call Options: Strike Price Below the Stock Price

ITM Put Options: Strike Price Above the Stock Price

Let’s revisit our TSLA trade briefly

Call Strike Price: 800

Stock Price: $836

So since this option has intrinsic value, it’s ITM. It’s that simple.

Out-of-the-Money (OTM) Options

Any option without intrinsic value is said to be “out-of-the-money (OTM)”.

OTM Call Options: Strike Price Above the Stock Price.

OTM Put Options: Strike Price Below the Stock Price

Here’s an example from our previous IWM trade.

Put Strike Price: $130

Stock Price: $130.71

Since the strike price is below the stock price, this option is therefore trading out-of-the-money, or composed 100% of extrinsic value.

At-the-Money (ATM) Options

Any option with a strike price very close to the current stock price is said to be “at-the-money (ATM)”.

Call/Put Strike Price: $150

Stock Price: $150.13

The strike price of an option doesn’t have to be trading at the exact price of the stock to be considered ATM. In the above trade, either a call or put with a strike of $150 would be considered ATM with a stock price of $150.13 (even though technically the call is ITM and the put is OTM).

Introduction to Shorting Options

So far, we have learned how to buy calls and buy puts. This is where most options traders stop learning. It is perhaps because of this that most options traders lose money.

I said before that options trading is a vast universe. To function in this universe, you must first understand how both buying and selling options work. Truth be told, more people make money selling options than by buying options.

We are now going to go over the very basics of short selling options. Even if you don’t want to short options “naked” (or sell without any protection), you must understand how selling options work if you want to incorporate options trading strategies such as “iron condors” and “vertical spreads”.

We asked you before to think of options trading as learning a new language. You have learned so far the basic grammar and vocabulary of buying options; let’s now extend that to selling options.

Now that you’re ready, let’s start by making an analogy to the stock market.

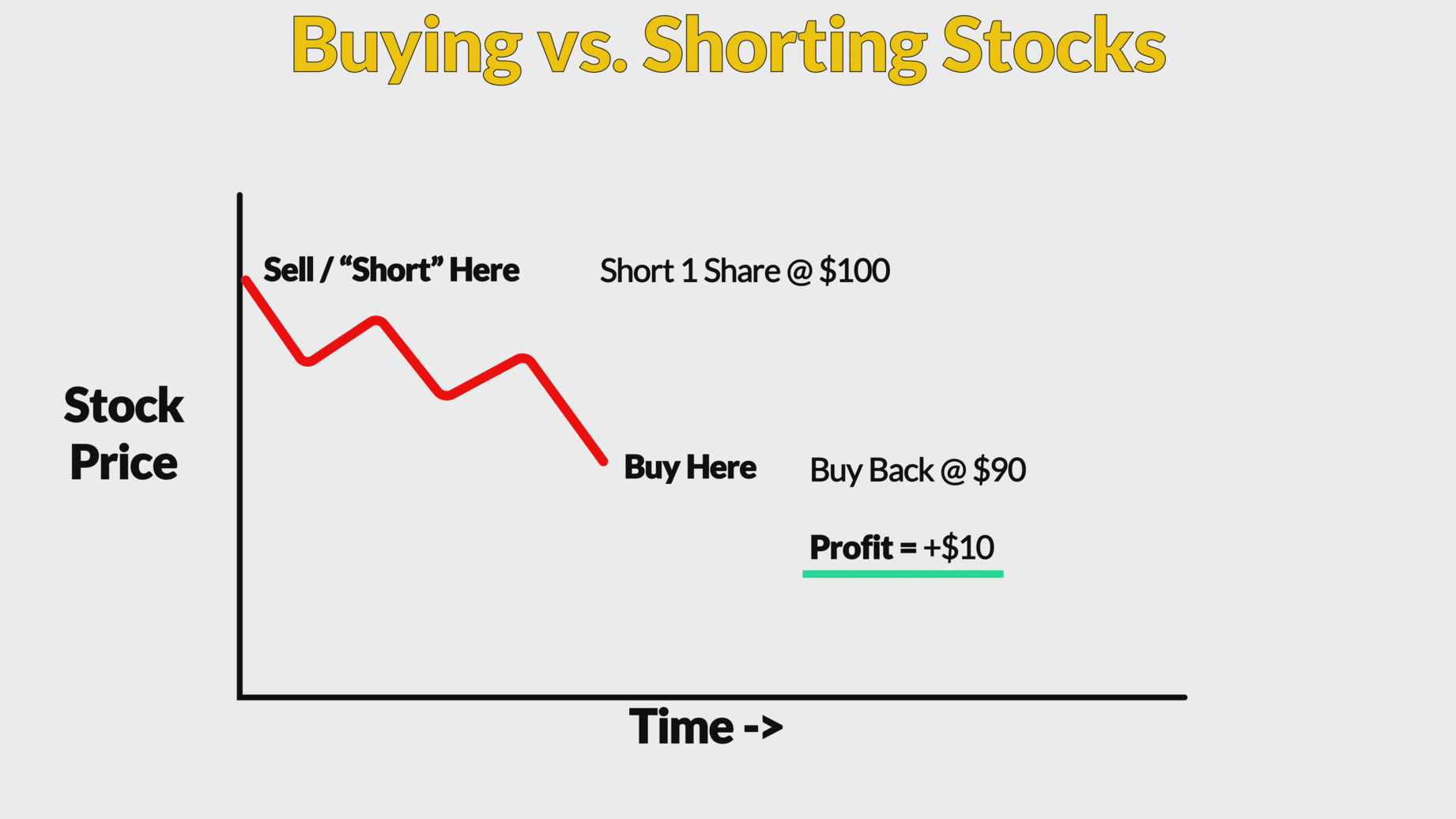

Buying vs Shorting Stocks

In the stock market, you can either buy or sell shares of stock. If you buy stock, you’ll profit when the stock goes up. If you sell a stock, you’ll profit if that stock goes down in value.

Let’s focus for a moment on selling stock.

Shorting stock refers to first selling a stock (that we don’t own) with the anticipation of buying it back later for a profit. This can get quite complicated, but for now, just think of it as easy and basic as buying stock, only flip everything on its head.

If we sell a stock for $100 (as seen above), then buy it back for $90, we will make a profit of $10/share. It’s that simple.

So why can’t we do this with options? We can, and options traders LOVE selling options (also called selling “premium”).

Just like with selling stock, we aim to sell an option high and buy it back low at a future date.

Shorting Call Options Introduction

Now that we have a basic idea of what a naked call looks like, let’s take a look at a trade now.

Opening Trade: Short a Call for $5.00 ($500 Credit Into My Account)

Closing Trade: Buy the Call for $3.00 ($300 Debit Out of My Account)

So if we sold the option for $5, and bought it back for $3, we just netted a profit of $2, or $200 in premium. Easy right?

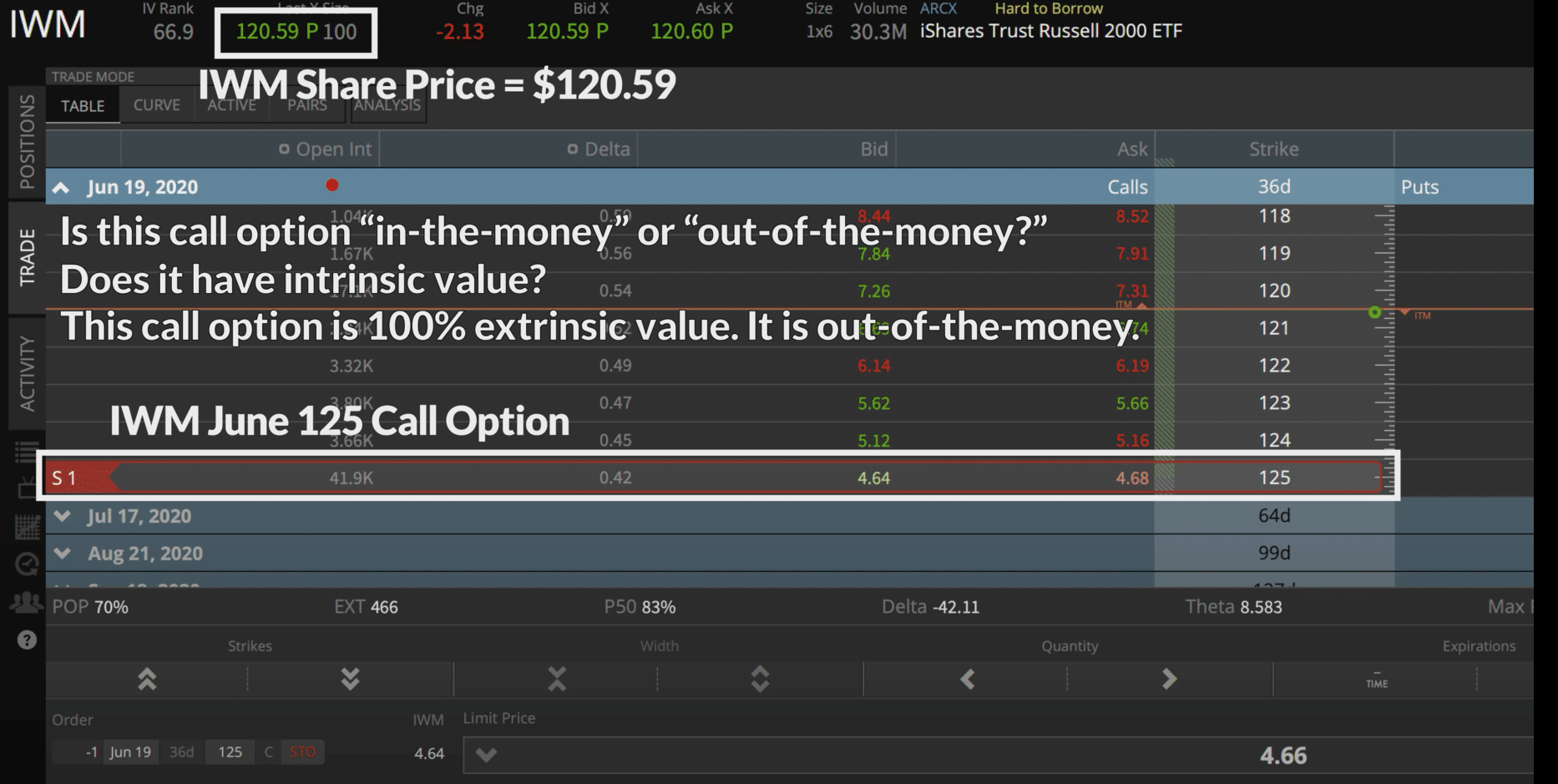

IWM Short Call Example

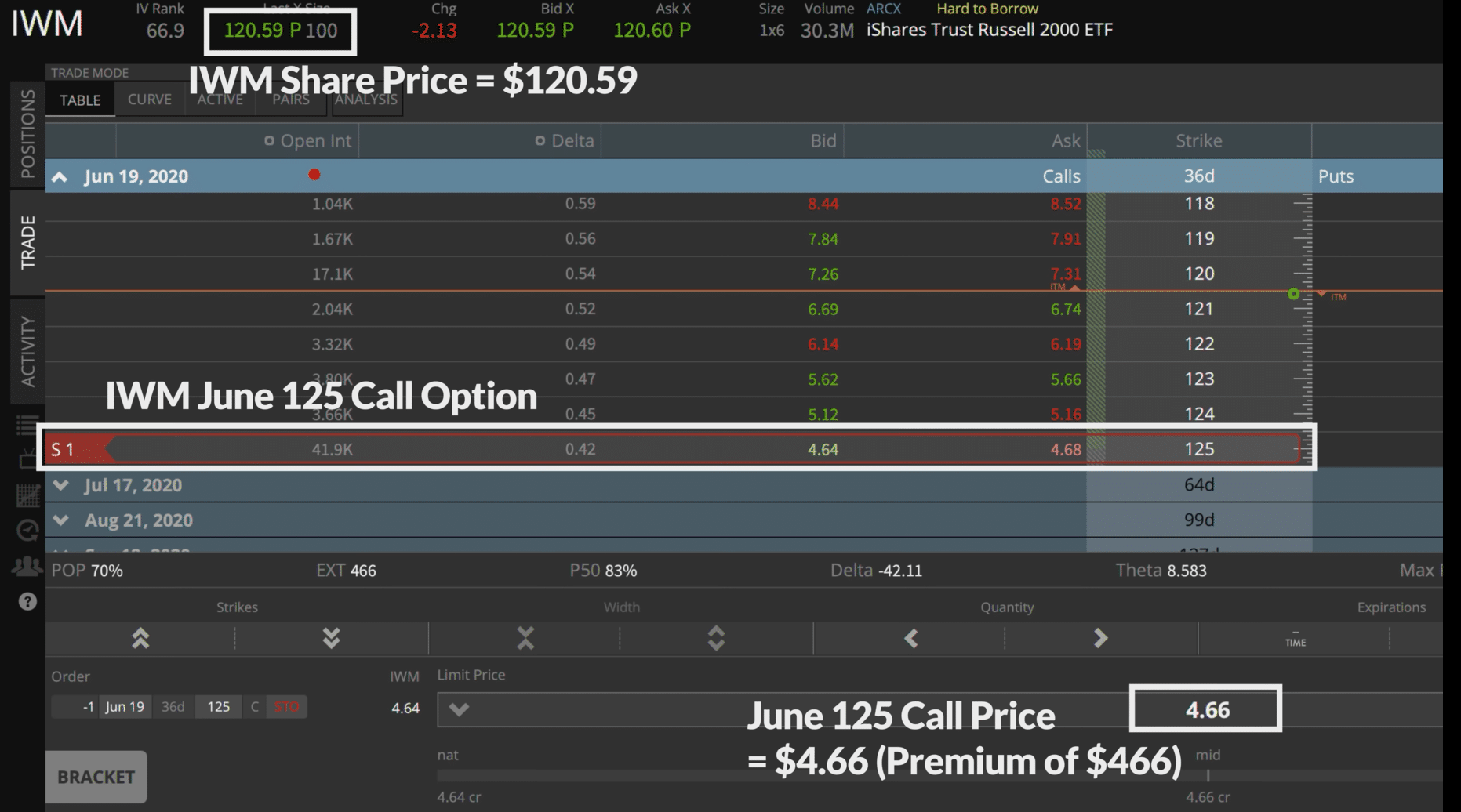

Now let’s take a look at a real-world example.

Here, we are looking at the IWM June 125 Call Option with 36 days to expiration. As we can see, the current share price of IWM is $120.59.

First of all, what does that tell us about the call options price? Does it have intrinsic value or is it only extrinsic value?

Since the strike price is $125, and IWM stock price is $120.59/share, we can tell that the option is out-of-the-money, therefore, its value is 100% extrinsic. In other words, its price is all “time value.”

As we discussed before, time value comes out of the option price as it approaches expiration. Remember that, then take a look at the below option price.

We can see that the price of the $125 IWM call option is $4.66, which means the premium is $466. When you sell or short an option, you don’t PAY the premium; you COLLECT the premium.

In this case, since the premium is $466, if we sell this option short, our account will be “credited” with $466.

Sounds nice, doesn’t it? Of course, there’s more to it than this.

Just because we collect the premium does not mean we have a profit; we must later CLOSE the trade and buy it for a lower premium to realize a profit.

As the option price falls, and if the stock price remains below $125, the profit on this position will slowly increase. It is a very fluid process and takes a bit of time and patience.

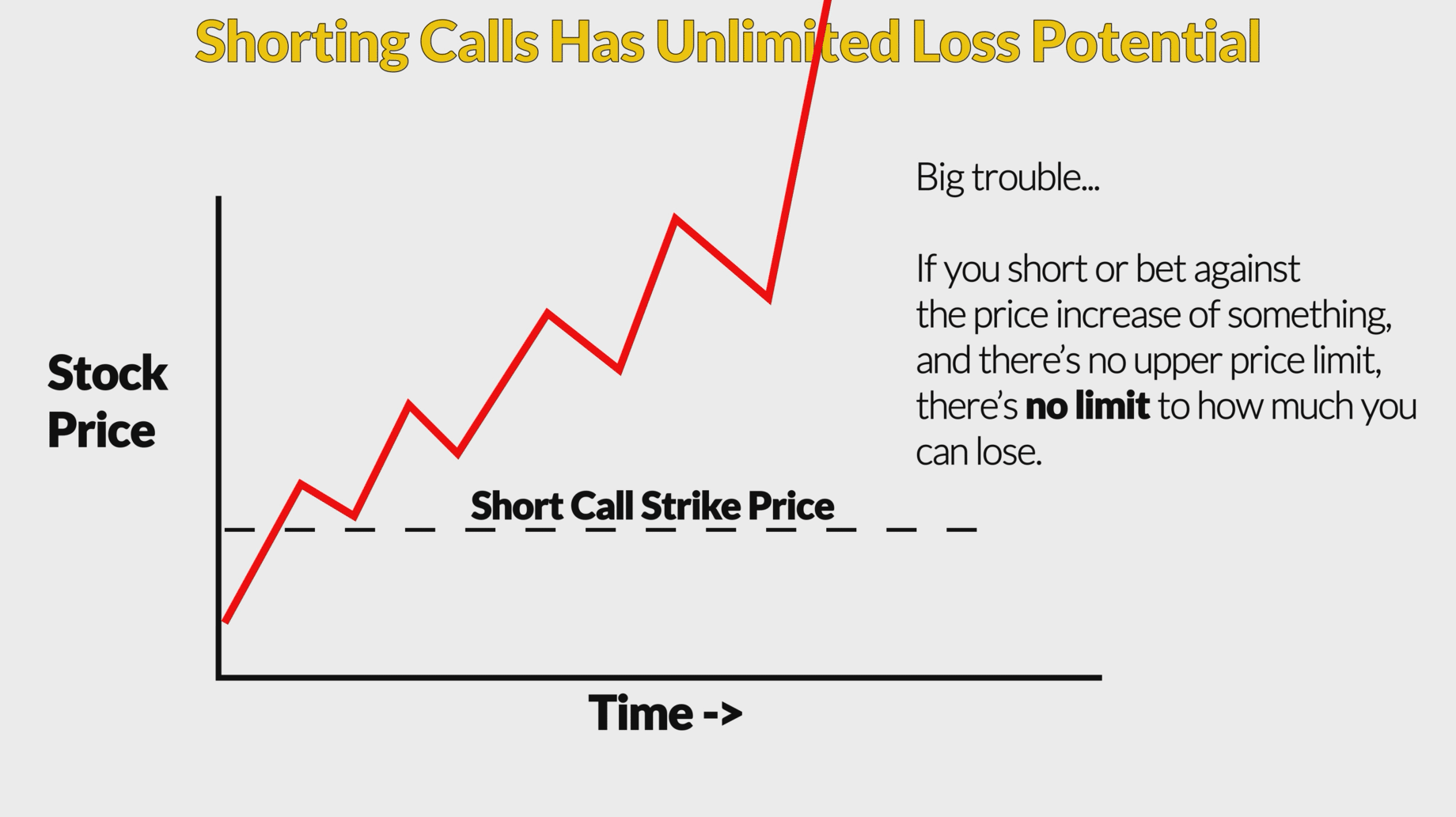

Shorting Calls Has Unlimited Loss Potential

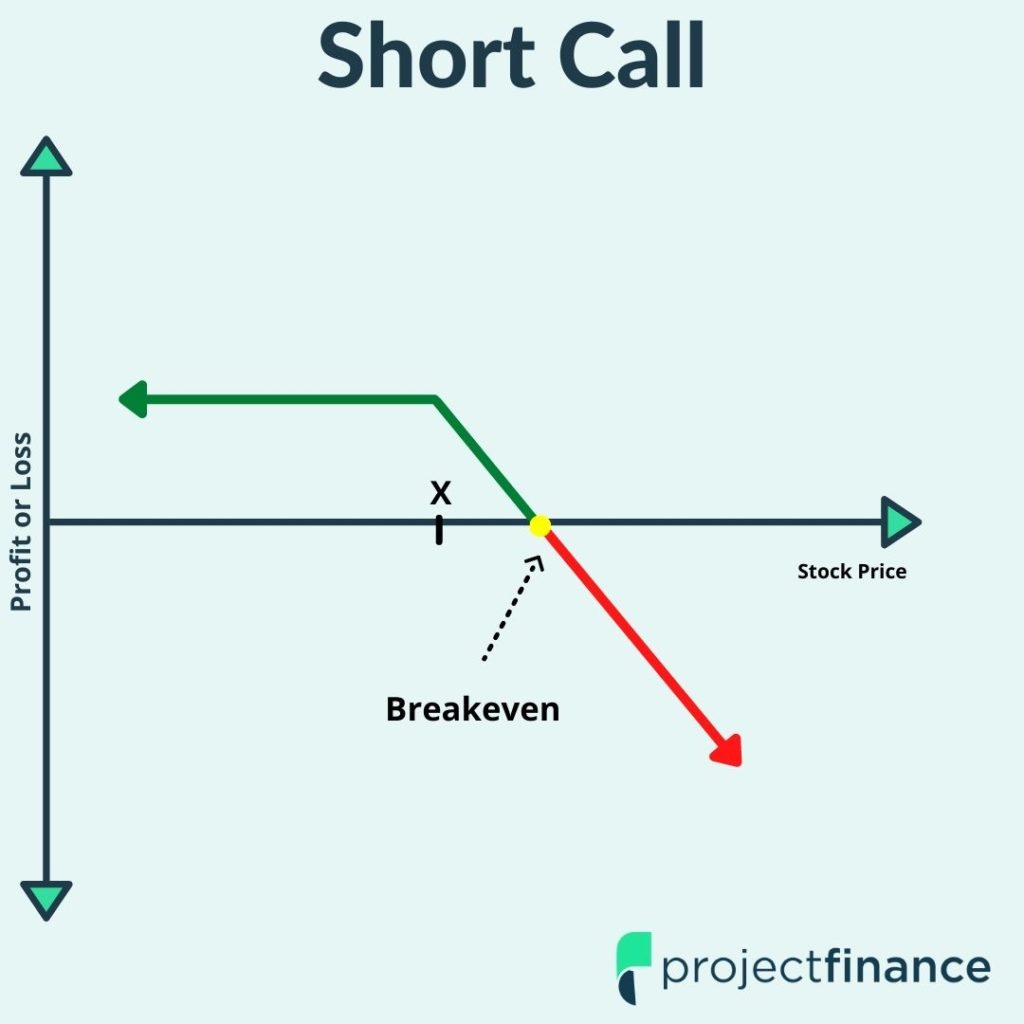

Take a look at the below image, which shows how a short call reacts to a rise in stock price.

What should concern you on this chart is the upward trend of that red line. Remember, the maximum loss on short calls is unbound; the stock can go up forever. Just imagine selling short a $20 strike price call on GameStop (GME) only to watch it rally to over $300!

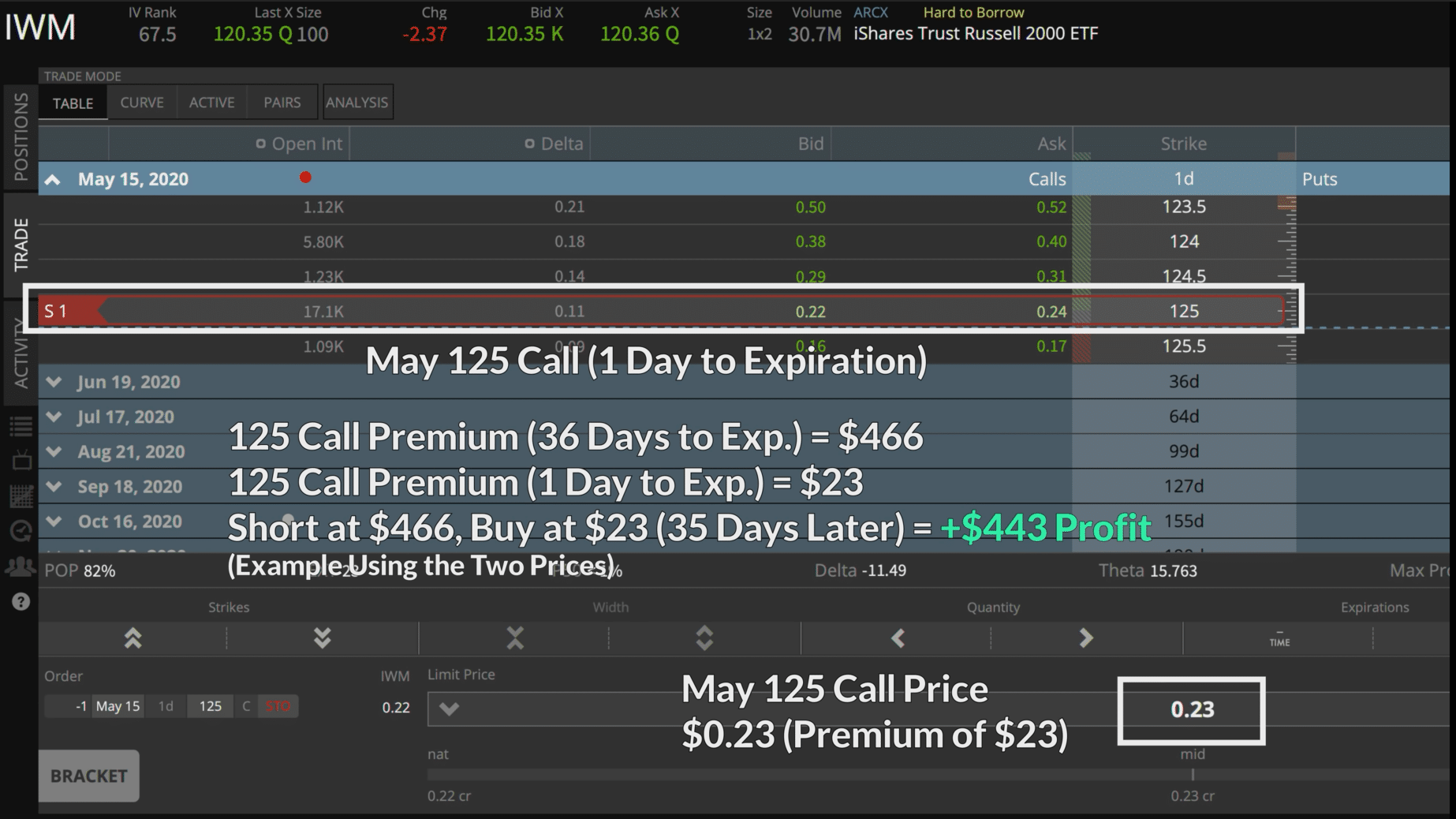

Let’s return our short IWM call, which we sold for a premium of $466. Let’s compare that strike price with the strike price of a similar IWM option closer to expiration.

We can see above that the price of the 125 call option expiring in one day is trading at $0.23, or a premium of $23.

This tells us that in a constant market, that option we sold short for a price of $4.66 with 36 days to expiration will be worth only $0.23 after the passage of 35 days. Why not zero? Well, there is still one day to go.

If we sell an option for $4.66, and then buy it back for $0.23 later, we will make a profit of $4.43 (4.66-0.23), or $443 in premium off the trade.

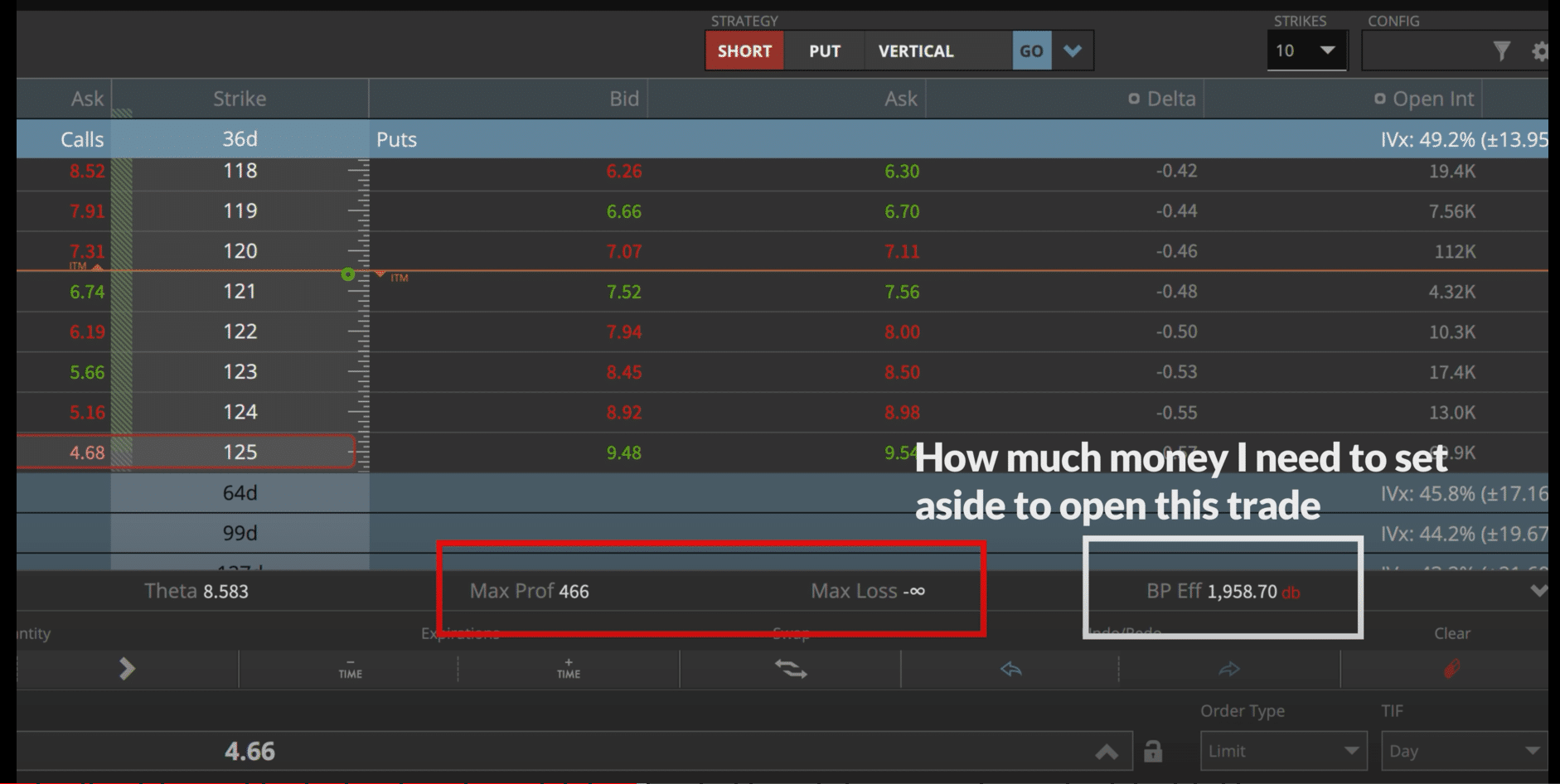

So knowing how much you can potentially lose on a short call, how does your broker let you place this trade? What do you have to “put down”? It can’t all be free!

Margin Required for Selling Options Short

You must have a margin account to sell short options. How much “margin” do you need to sell a naked call?

That depends on the trade you are doing and the risk involved. The formulas that different brokers use can get quite complicated. Luckily, it’s calculated for us.

We can see that to sell this IWM call, tastyworks requires $1,958.70 to be held on margin, or “in reserve” should that trade go against you. This is a lot of money. Therefore, you must also consider “opportunity lost” when selling options. What else could you have used that money for?

Now let’s take a look at a “naked” call option that doesn’t work in our favor.

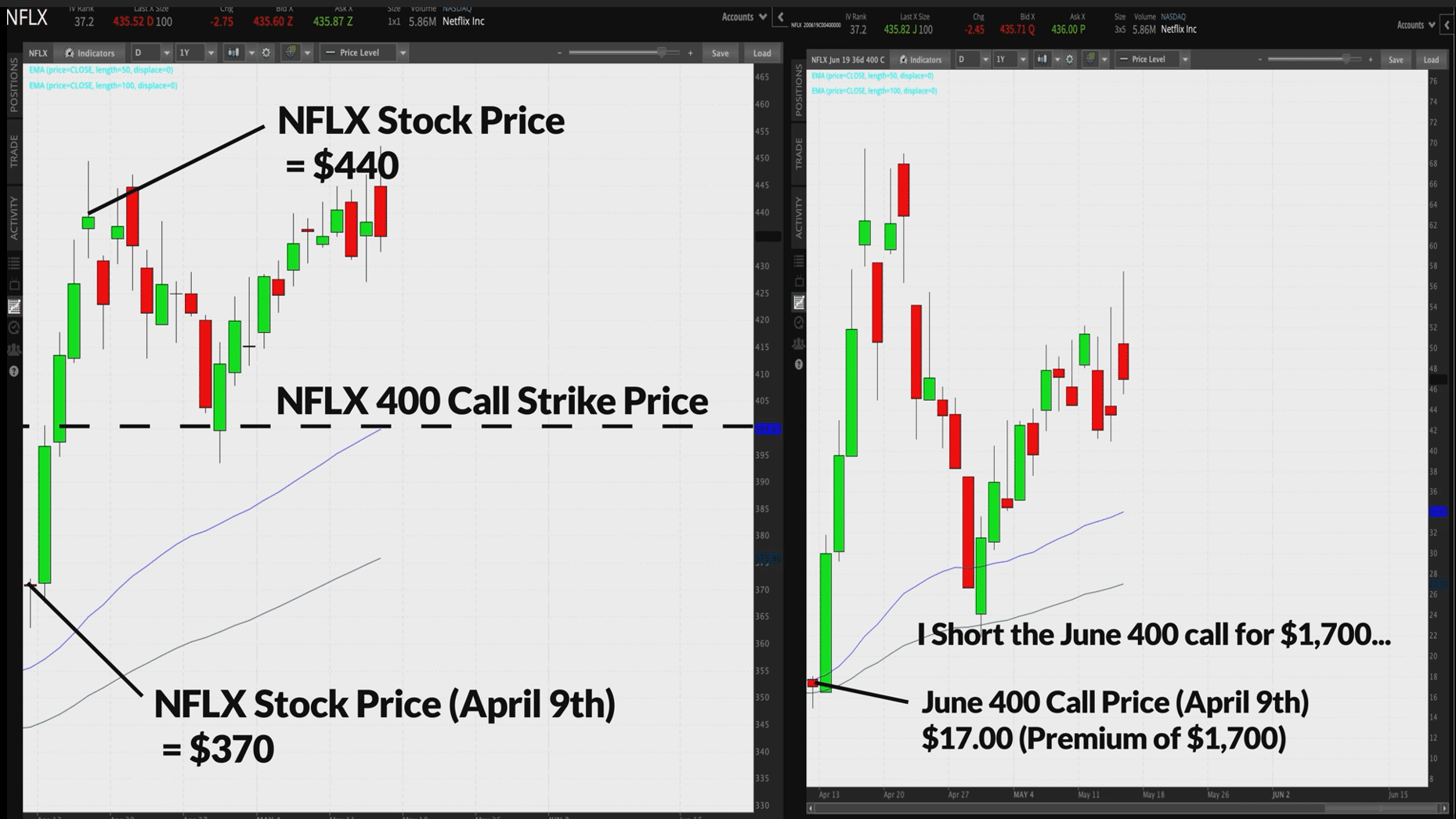

Netflix (NFLX) Short Call Example (Big Loss)

In this example, we are going to see a significant rise in stock price after we sell short a call option.

Take a look at the below image. On the left-hand side, you will see a chart of the stock price; on the right hand side, you will see a chart of our short option.

Here are the details of our short trade:

NFLX Share Price: $370

Expiration: June

Strike: 400 Call

Option Price: $17 (Credit of $1,700 to our account)

In the above trade, we went short a call option (the 140 Call) for $17 just days before the underlying NFLX stock skyrocketed in value. If we were long that call it would be winner-winner-chicken-dinner, but we decided to sell it instead.

Remember, trader’s sell short calls when they believe the underlying stock price is either going to stay the same, or go down in value.

Before we examine our trade results after just a few days, I want you to recall the maximum loss you can incur on a LONG call; which is always the debit paid. If we bought this call instead of selling it, we would have had a maximum loss of $17 (or $1,700).

But we sold it.

So how much is our trade down after just a few days? More than $17, a lot more actually!

Here is our trade updated to reflect a rise in NFLX:

NFLX Share Price: $370 —> $440

Expiration: June

Strike: 400 Call

Option Price: $17 —-> $62.50

Since the stock rallied $70 in a short amount of time, our short call option got hammered. We sold the call for $17. Therefore, the most we can ever make on this trade is that $17, or a premium of $1,700.

But we lost money here, a whole lot. Since the option we sold for $17 is trading at $62.50, our loss is $45.50 so far on the trade (or $4,550).

Ouch!

We lost $4,550 in a scenario where our maximum profit was $1,700. You don’t have to be a financial expert to know this isn’t a good risk/reward profile.

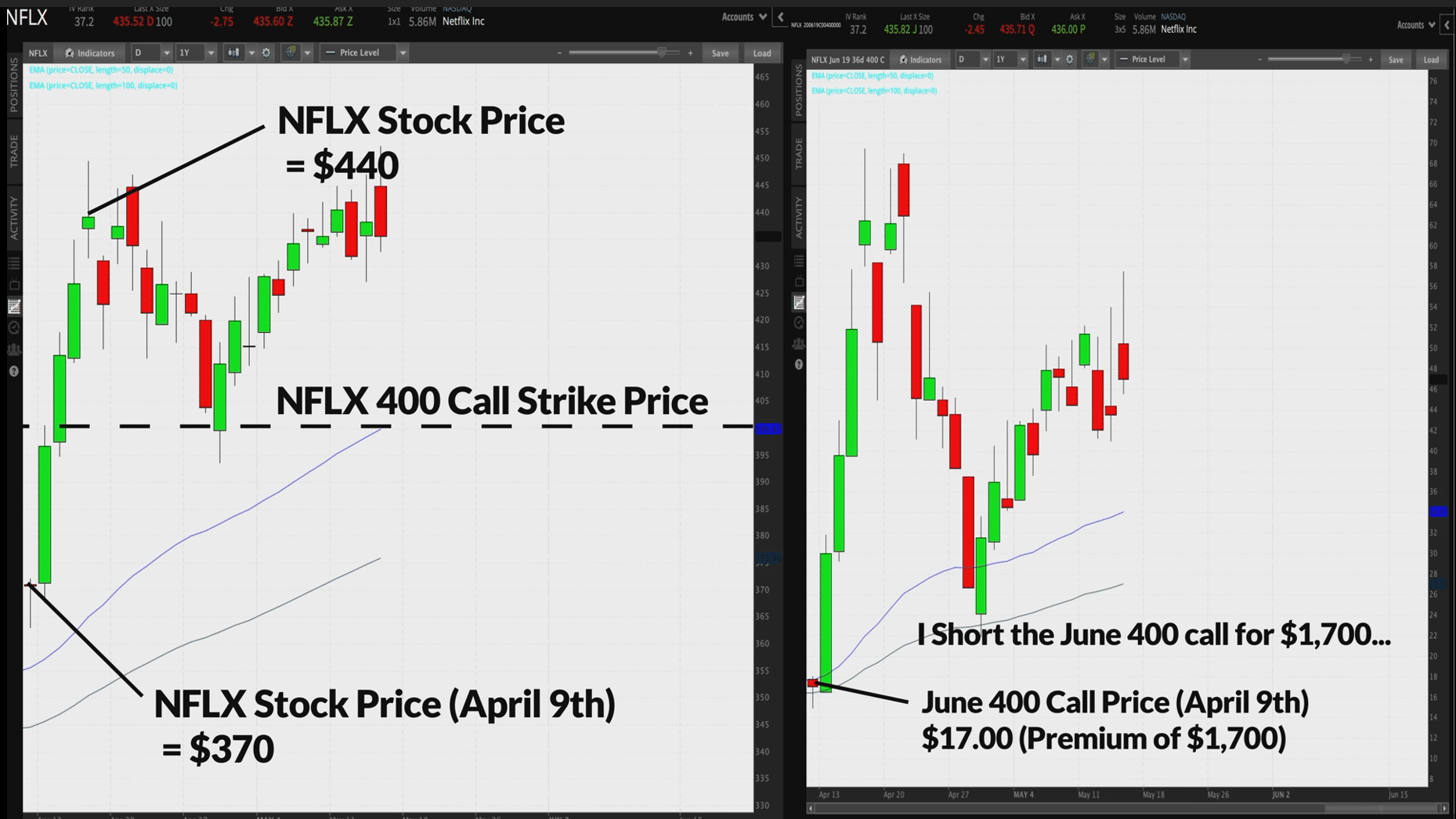

Short Call Breakeven Price Explanation + Illustration

Now, we are going to discuss how it is indeed possible to make money off of a short call option position when the stock price breaches the strike price of the call option we sold.

This is because of something called “Breakeven Price”. Remember, to determine the profit/loss on an options position, you must also include the debit paid or the credit received.

Let’s take a look at a visual to help you better understand this.

If you short a call option with a strike price of $400 for a net credit received of $17 (like we did above), at what price would the stock have to be in order for our option to be worth $17 or less at expiration?

This should be quite easy: since we sold the 400 call for $17, any stock price under $417/share will make our trade profitable. Remember, we want our short call to go down in value.

In order to determine the breakeven point, we must determine the price at which our 400 call has an intrinsic value equal to our sale credit of $17.

More simply, the breakeven on a short call position is simply strike price + option premium sold.

Here’s another visual to help.

The above example shows NFLX stock closing at $417 on expiration. Since we sold the $400 call for $17, we would breakeven on this trade.

If NFLX closed at $410/share instead on expiration, can you guess what our profit/loss would be?

Simply subtracting our option breakeven price from the market price ($417-$410) gives us $7, or a profit of $700.

So even though our short call was in the money at expiration, we still made money.

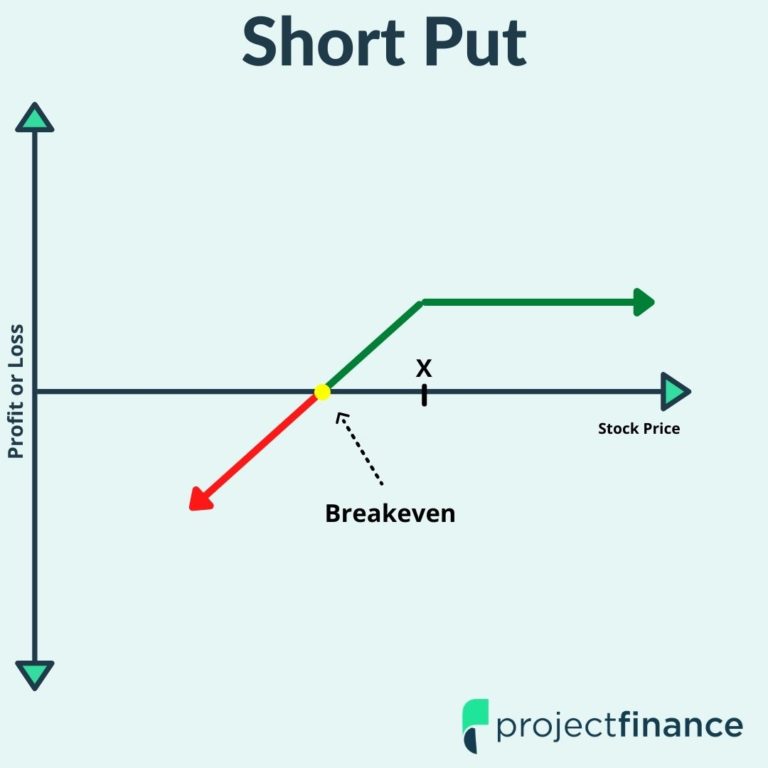

Shorting Put Options Introduction

Last on our list is the short put strategy. Remember, all options trading strategies are a combination of long puts/calls and short puts/calls.

After learning the mechanics of short puts, learning more advanced strategies such as the “diagonal” spread should be quite easy.

Similar to shorting calls, shorting put options involves selling options that you do not own. Shorting putting may take a bit of time to understand as it can come off as counterintuitive.

Usually, when you short something, you believe the underlying price will go down in value. But with puts, just the opposite is true. If a long put makes money when the market falls, then selling that put must make money when the market rises.

It is because of this that selling put options is a bullish strategy.

Take a minute to process that. It will make what is to come much easier.

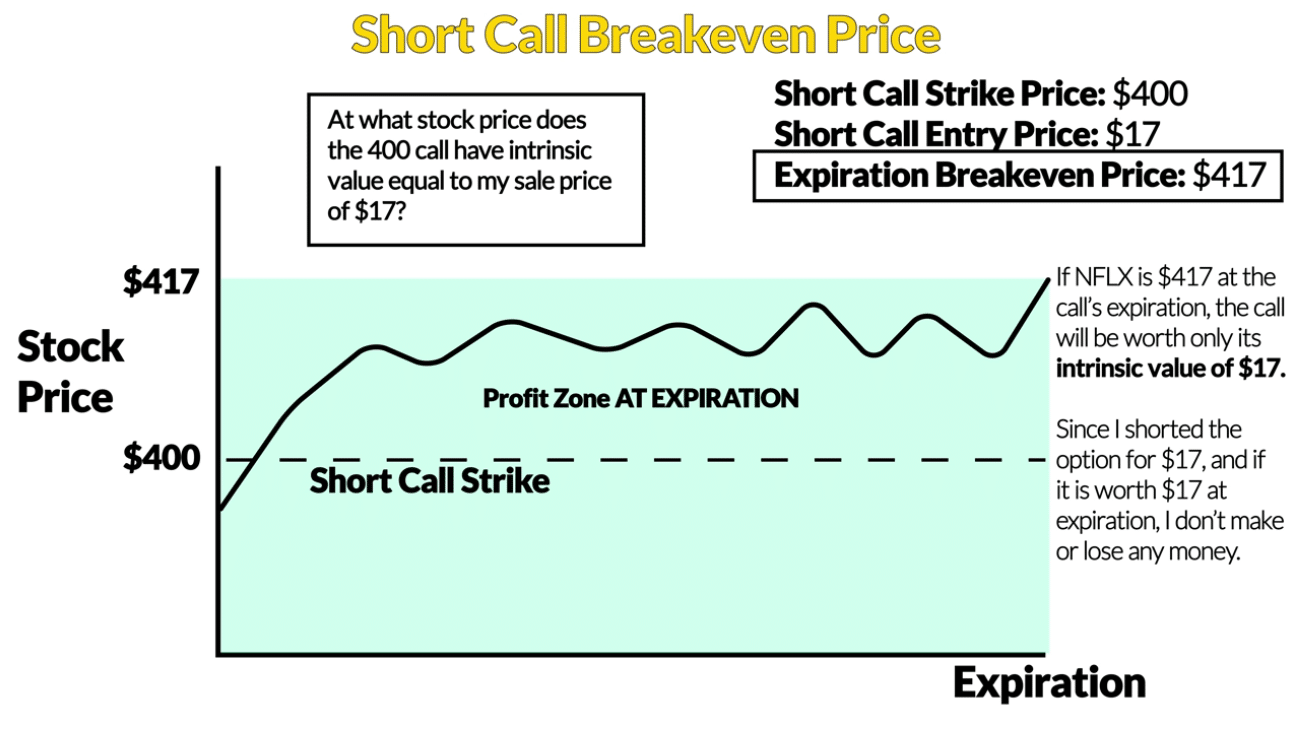

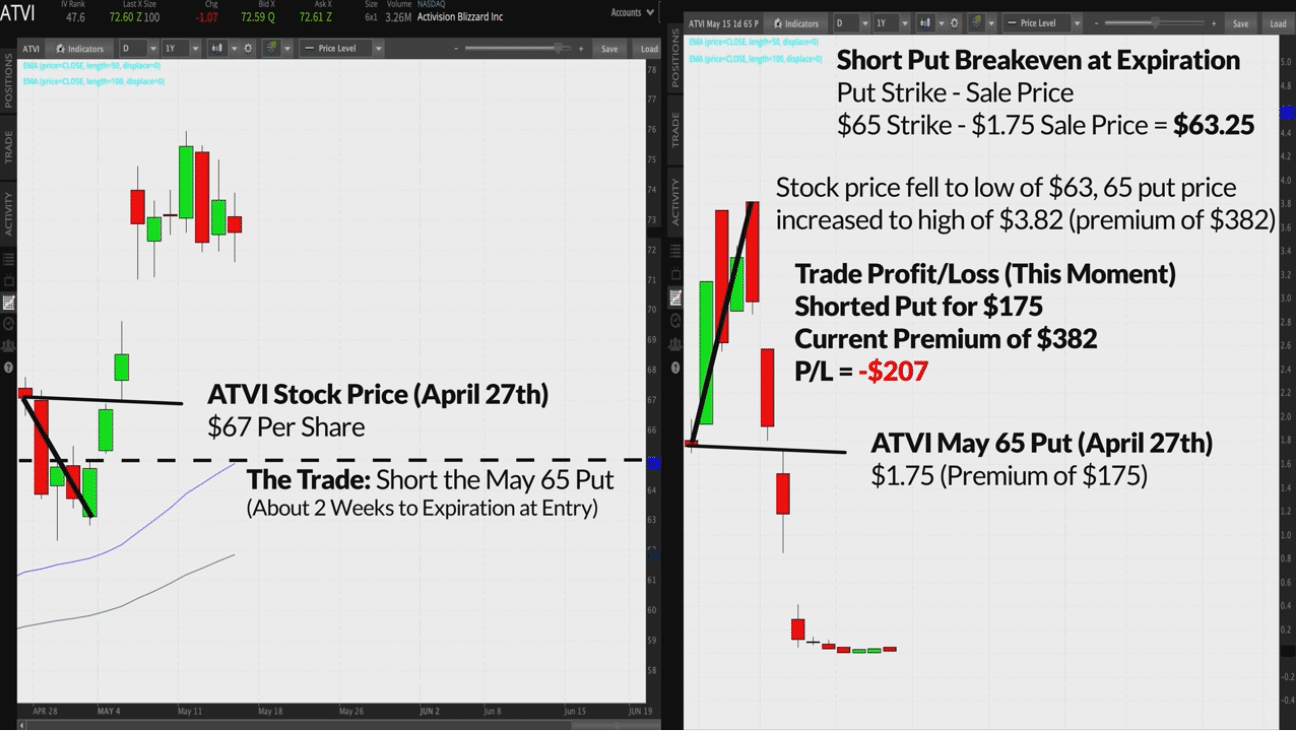

Activision (ATVI) Short Put Example

In this example, we are going to look at a short put option on ATVI.

And here are our trade details:

ATVI Share Price: $67

Expiration: May (2 Weeks Away)

Strike: 65 Put

Option Price: $1.75

So we just sold a put. What does that mean? It means we think the price of ATVI is either going to stay the same or go up. Even though we are BULLISH on ATVI, we are short an option. Again, since long puts lose money when the market goes up, short puts must make money when the market goes up.

That is exactly what happened here; the stock price went up, and the value of our short put went down. That’s good news!

Breakeven is always a great place to start. Remember, breakeven is the expiration price of the stock where we will not make or lose money on our options. This was quite easy to calculate for calls. Put can be more complicated. Can you figure out our breakeven price here intuitively?

Since the breakeven for short calls is strike price + premium sold, the breakeven on short puts must be strike price – premium sold. Remember, puts have intrinsic value when the price is BELOW the strike price, just the opposite of calls.

Our strike price is 65. Our premium received was $1.75. Therefore, our breakeven price on this short put is $63.25/share at expiration (65 – 1.75).

So this trade ultimately looks like it was a winner. But that wasn’t always the case. Notice how the stock sold off in the early days of the options life? How was our short put performing then?

We can see that our journey to $0 was not an easy one. During the early days of the options life, the stock nosedived. This led to a subsequent rise in the price of our short put.

We can see that at one point, our short put option was trading at $3.82! That’s more than TWICE what we sold it for! In other words (for a short time) we were losing more than we could have made on the trade (which is always the credit received on short options).

You must have nerves of steel to sell short options.

But in the end, the stock rallied, and our option plummeted in price. Good news.

If we bought that option back for around $0.02 cents in the last days of trading, that would give us a profit of (1.75 – 0.2) $1.73, or $173 in premium. That’s a nice trade.

ATVI Share Price: $67 —-> $72.59

Expiration: May (2 Weeks Away)

Strike: 65 Put

Option Price: $1.75-—> $0.02

Thoughts on Holding Short Options Through Expiration

Now we could have just let that put expire worthless and collect the FULL $1.75 in premium, but that involves more risk. Who knows what the stock will do in its final days/hours of trading. Trade smart!

Great! Now you have learned the 4 basic options trades. You did it!

Implied Volatility Introduction

Implied volatility. Two of the most dreaded words in the option traders education!

But don’t be intimated. It’s not that complicated, I promise.

If you want to trade options successfully, you must understand implied volatility. Period. That’s all there is to it. Let’s look at the definition, then understand what that definition means.

Implied Volatility: A metric that represents the expected volatility of a stock over the life of the option.

Let’s break implied volatility down.

Implied: “Expected”.

Volatility: Magnitude of Stock Price Changes.

So implied volatility (IV) is therefore simply the expected magnitude of stock price change.

So what is it exactly that “implies” the expected move of a stock? Options! You can use options to your advantage even if you don’t want to trade them. They give you a window into the stability of a stock.

Implied Volatility Example: Comparing Two Stocks

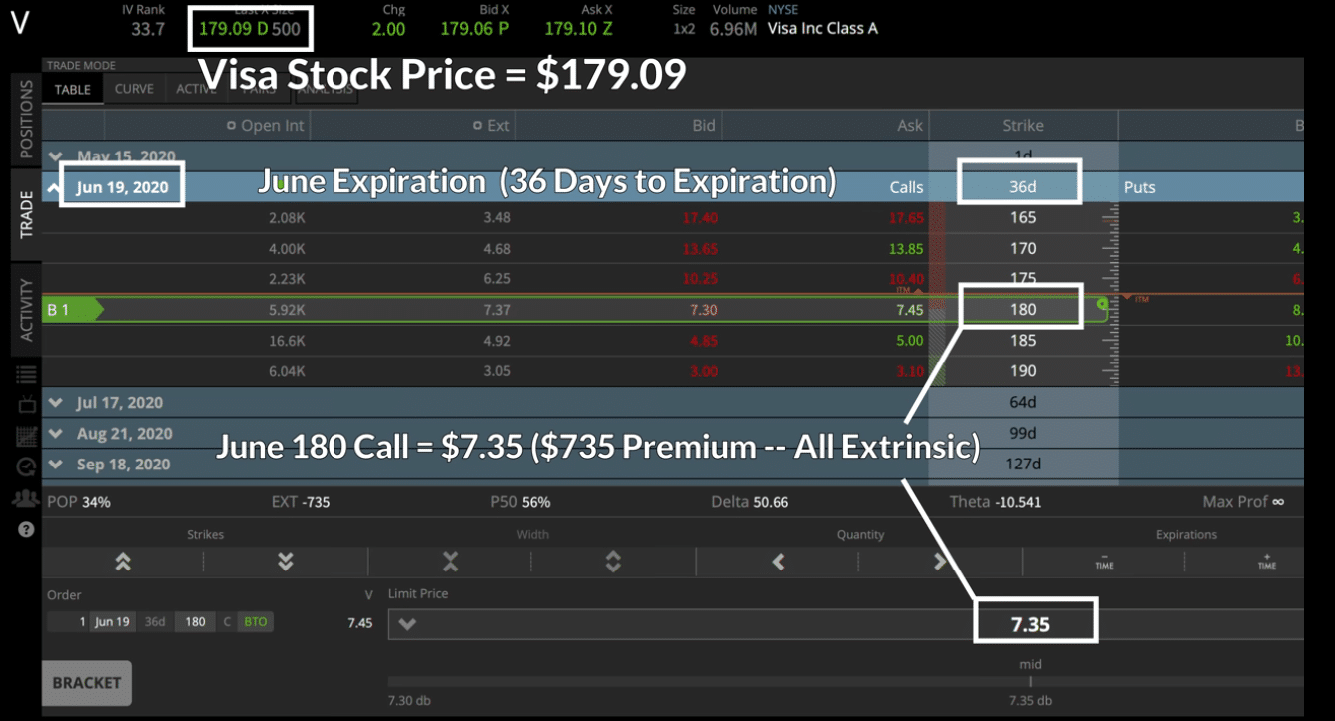

The first stock we are going to look at is Visa (V).

Here are the details of our trade.

V Share Price: $179.09

Expiration: Jun 19

Strike: 180 Call

Option Price: $7.35

Since our call strike price is higher than the current stock price, we are dealing with an out-of-the-money call.

Therefore, that $7.35 in option premium is entirely extrinsic value.

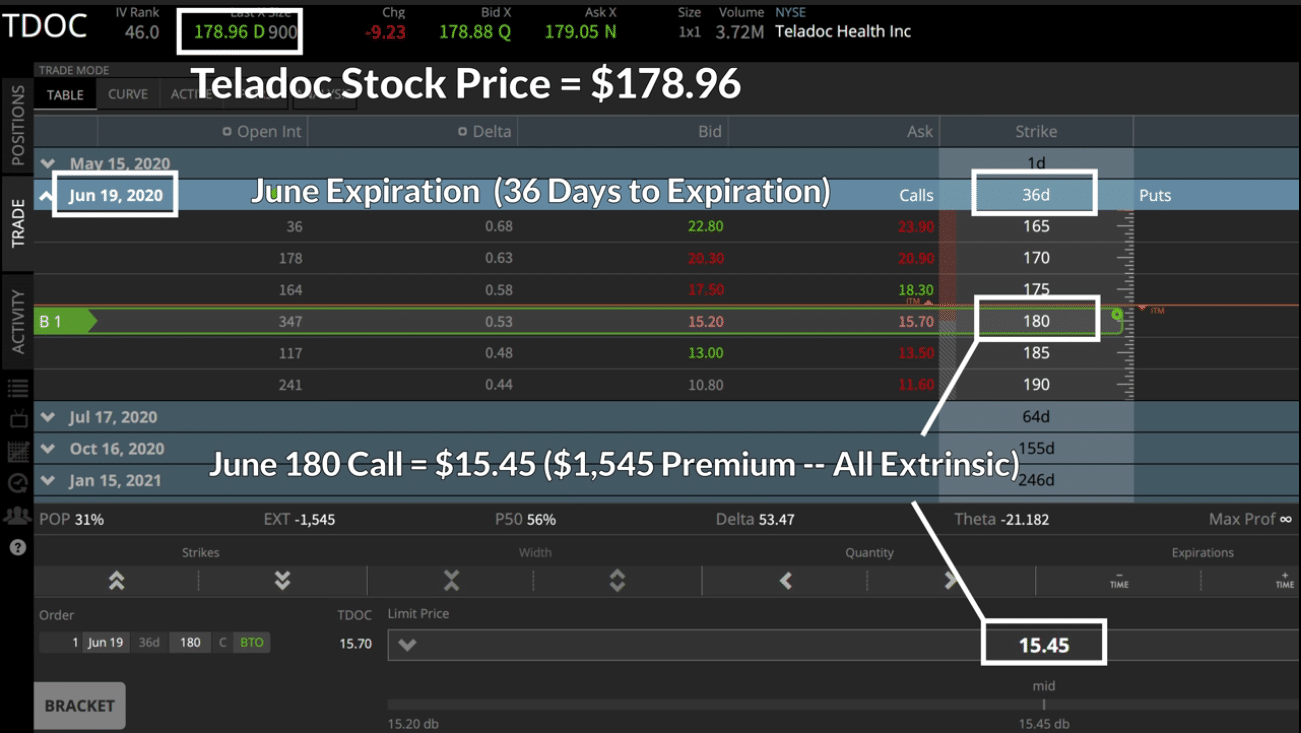

OK. Let’s load up the data on our second trade. (IV is understood best by comparison).

TDOC Share Price: $178.96

Expiration: Jun 19

Strike: 180 Call

Option Price: $15.34

So both of these options (V and TDOC) are out-of-the money. Additionally, the strike price is the same. On top of that, the stock price is also about the same.

So why is there such a HUGE difference in premium?

The 180 V calls are trading at $7.35; the 180 TDOC calls are trading at $15.45.

The answer lay in implied volatility (IV). The IV for TDOC is much higher than that of V. The market is expecting TDOC shares to move more than V shares. It’s that simple.

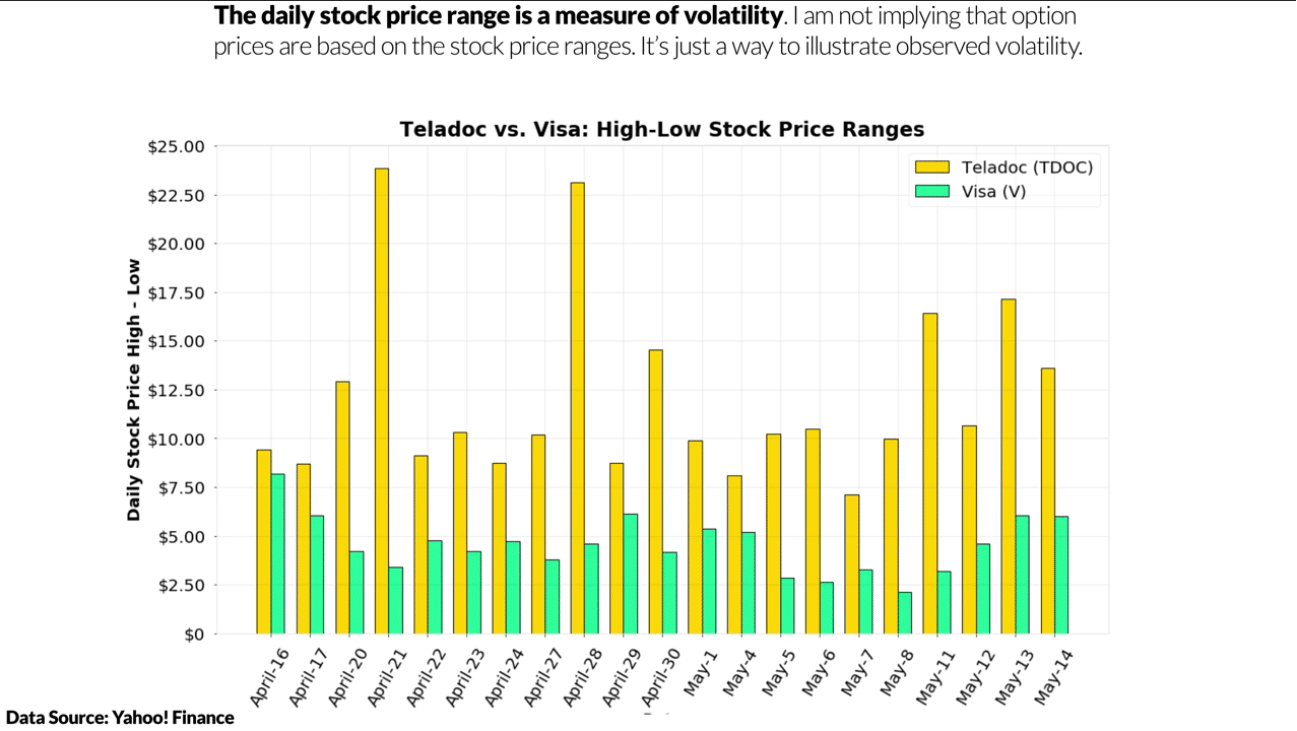

So why is this? Why would the market think this? Let’s look at their respective historic share prices to understand.

Comparing Visa (V) and Teladoc (TDOC) Stocks: High-Low

Take a minute to compare the two stocks below.

The above image compares the high-low trading range of TDOC to V.

We can see that TDOC trades at a much wider range than V. For example, on May 14th, the high-low range on V was $6; on this same day, the high-low range on TDOC was over $13.

The “observed” volatility is thus greater in TDOC.

In summary, if two stocks are trading at the same price and the premiums for the options at a particular strike price are greater for one of these stocks, that stock has a greater IV.

If you’d like to learn more about implied volatility, please watch our below video. This is important stuff folks!

Implied Volatility for Beginners

Next up is an overview of the exercisement/assignment process. Don’t worry, the hard stuff is now behind you!

Exercise & Assignment Explained

We touched on exercise & assignment earlier. Let’s now take a closer look at how options can in theory be settled.

Frankly, you probably won’t need to worry about exercise and assignment much, but understanding the mechanics of this process is integral to your options trading education. Short call and put options are rarely assigned.

Long Option Traders Have the Right to Exercise

When you have purchased options, you can exercise them, which converts the contracts into stock (100 shares/option).

Exercise a Call You Own: Buy 100 Shares at the Call’s Strike Price.

Exercise a Put You Own: Sell 100 Shares at the Put’s Strike Price.

As we discussed, the value of this ability is why options become more or less valuable as the price changes, time passes or expectancy volatility changes.

That covers the “exercise” portion, which the owners of call and put options have the right to do.

But what about the “assignment” process?

Short Option Traders Get Assigned

If you decide to exercise your long options, doesn’t somebody have to give you those shares? That’s where assignment comes into play; short options sellers can only ever be assigned, they don’t have the right to exercise.

When an option gets exercised, the trader who is short that option gets assigned, which is called options assignment.

Short Call Trader Assigned: Assigned -100 Shares at the strike price.

Short Put Trader Assigned: Assigned +100 shares at the put’s strike price.

When assigned on your short option, your options position is converted into the corresponding share position as described above.

So what are the ways this process happens? Let’s look at that next.

Expiration and Automatic Exercise/Assignment

At expiration, any long options position that is in the money by one penny or more will typically be automatically exercised.

Long Option Assignment/Exercise

Let’s say you own a $105 call and the stock closes at $105.01. On expiration day, there is a good chance that the long call option is “automatically” exercised by your broker, thus converting that call into 100 long shares.

If you own a $110 put and the stock closes at $109.99 on expiration, there is an equally good chance your long put will be automatically exercised and you will automatically short the stock at $110.

This is done automatically by your broker.

Short Assignment/Exercise

So we looked at how long options can get automatically exercised; guess what happens to the trader who is short that very option you just exercised?

If you are short a $105 call and the stock closes at $105.01 on expiration day, there is a good chance that your short call option is automatically assigned by your broker, thus converting that call into 100 short shares.

If you are short a $110 put and the stock closes at $109.99 on expiration, there is an equally good chance your short put will be automatically assigned and you will automatically buy the stock at $110.

Again, this is automated by your broker.

Why?

There is intrinsic value in these options, and if you don’t exercise them, you will forfeit this value. Your broker is looking out for you!

But remember, stock sometimes costs A LOT more than the option on that stock (just think how much 100 shares of AMZN would cost you!). So make sure you have the funds to hold those shares, or your broker will automatically liquidate them.

You won’t see the stock in your account until Saturday sometimes if it’s a Friday expiration, but you’ll definitely have the shares by market open the following day.

This is why it is highly recommended to trade out of in-the-money options (long or short) before expiration.

Why Options Are Rarely Exercised Before Expiration

But what about “early” exercises and assignments? Long options can be exercised at any time; you don’t have to wait until expiration. Should shorts be worried?

This is a very common fear of new options traders. Here’s why you shouldn’t worry.

Any extrinsic value that exists in an option will be lost when exercising it. In other words, if you are assigned on a short option position with extrinsic value, that’s free money to you!

Let’s see why next in the below generic trade example.

Stock Price: $105

Option: Long 100 call

Call Price: $10 ($500 Intrinsic Value; $500 Extrinsic value

If you exercise this option, you will buy 100 shares of stock at $100. But the stock price is at $105. This means you buy a $10,500 position for $10,000 (a $500 gain).

Nice gain, but you just gave up that extra $500 you could have got from the option’s extrinsic value! You could have made $1,000 had you simply sold the option as opposed to exercising it.

If you were short this very call, wouldn’t you want the long party to exercise then! You betcha.

This is why early assignment is rarely an issue.

Which Options to Trade? Consider Liquidity

So what stock should you be trading options on? Not all stocks. In truth, probably not MOST stock’s.

Why?

Something called liquidity.

The more market participants you have, the greater liquidity you will have. Think of it this way. Let’s say you have tickets to some esoteric punk band that nobody’s ever heard of. Will it be harder selling these tickets when compared to, say, U2 performing at Wrigley Field? The U2 concert will probably have tighter markets, meaning you won’t have to sacrifice much of your initial purchase price when you sell the tickets.

So how do you find options markets that have many participants?

As a general rule, stick to stocks that have a daily trading volume in the millions. In addition to the liquidity of the stock, we need to look at the liquidity of the options themselves. This can be done in three ways.

- Option Open Interest

Open interest indicates the total number of option contracts that are currently in existence for a particular contract. You want to make sure you’re not the only party long a particular option!

- Narrow Bid/Ask Spreads

The bid-ask spread is the amount by which the ask price exceeds the bid price for an option in the market.

If an option is bid at 1.40 and offered at 2.50, you’ll probably realize a loss right away. Why? You won’t be able to sell it anywhere near the offer price. You want TIGHT MARKETS when trading options.

The SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) has the greatest liquidity in the world, and many times SPY options are only a penny wide.

- Option Volume

Lastly, you want to look at the volume of that particular option your trading. Option volume is the total number of option contracts bought and sold for the day, for a specific option.

If a contract has traded 2 contracts all day, that isn’t a good sign. This is a subjective process, but you definitely want a decent amount of volume.

All of these three metrics can be found on the tastyworks trading software.

Stock with Great Liquidity

Here are a few stocks and ETFs (exchange-traded funds) with fantastic liquidity:

Index ETFs: SPY, IWM, QQQ

Equities: AAPL, AMD, C, INTC, TSLA, FB, NFLX (Companies)

Index Options: SPX, VIX, NDX

Final Word

Phew. You made it! Congrats! That was a lot of information. Let’s recap quickly some of the key points we went over, starting with calls vs puts.

Lastly, let’s fly over some of the more important information in a few bullets, then you’ll be done!

- An option almost always has a multiplier of 100 as it represents 100 shares of stock

- "Intrinsic value" tell us how much an option is "in-the-money" by

- "Extrinsic value" represents the time value of an option, and is calculated by subtracting the intrinsic value from the full option premium

- "Implied volatility" forecasts a likely movement in a stock's price

- "Moneyness" refers to an option's relative location to the current stock price

- Assignment worries are generally overblown; assignment can be a good thing!

We will leave you on this final note. When starting off in options trading, it is important to trade small. Trade small, lose small!

Chances are, you have some additional questions. If we can’t help you directly, please feel free to reach out to the folks at Tastyworks. They are the best in the business!

Happy trading!