Last updated on February 14th, 2022 , 08:22 am

Short Call And Put Options Are Rarely Assigned. Here’s Why.

Jump To

In fifteen years as an options broker, I don’t recall once dealing with an advisor or customer who traded options with the intent of transferring their options into stock, which happens during the exercise/assign process. Whenever assignments did happen, there was seldom a happy person on the other end of the line.

This makes sense – if you want the stock, why not just buy/sell it outright? You have infinite flexibility when buying/selling stock. You can choose the number of shares, the price of execution, and even the time of your fill.

This isn’t always the case with options. When we’re talking option assignment/exercisement, we’re talking about round lots of 100 shares. This is very costly and rarely matches an investor’s risk profile (100 shares of AMZN would currently cost you $360,000). Additionally, with short option positions, sometimes you don’t know when/if you’ll be assigned.

Assignment Risk Odds

This assignment risk, however, is often minimal and can be mitigated entirely if you understand the product you are trading. In this article, projectoption takes a deep dive into option assignment and shows why this common fear for investors short call and put options rarely materializes. At the heart of the rationale behind all option exercisements and assignments is something called “extrinsic value”, which we will examine closely.

Before we get started, let’s do a brief recap of how the exercise/assign process works. We are first going to do a recap of American and European styled options as the latter has no assignment risk.

Highlights

- Only “American Style” options can be early exercised/assigned.

- An option’s value is composed entirely of “intrinsic” or “extrinsic” value.

- Intrinsic value is the amount an option is in-the-money-by.

- Extrinsic value (implied volatility + time decay) is the difference between the market price of an option and its intrinsic value.

- In-the-money call options could face dividend-risk.

Why Options Are Rarely Assigned

New to options trading? Learn the essential concepts of options trading with our FREE 160+ page Options Trading for Beginners PDF.

European vs American Style Options

If you own a call or put option, you generally will have the right to exercise that option at any time before the expiration. The exception to this rule is European-style options, such as S&P 500 Index (SPX) and the NASDAQ-100 Index (NDX). These index options are cash-settled at the expiration date, so they cannot be exercised prior to expiration.

However, the vast majority of tradable options are American style, meaning they can be exercised at any time. This applies to nearly all options on equities. If you’d like an education on how these two styles of options differ, please read our article SPX vs SPY: Here’s How They Differ. If you’re interest in trading volatility, our VIX vs VIX article may be more fitting.

Since there is no assignment risk with European Style index options, this article is going to focus on American style options. If you truly want to eradicate all risks of early assignment, simply stick with European styled options and you’ll have nothing to worry about.

Exercising a Call/Put Option

The owner of long (American style) call and put options have the right to exercise their position at any time prior to that options expiration. If you exercise a call option, you will convert that option into stock by purchasing 100 shares of the underlying stock at the call’s stock price.

If you are long a call option with a strike price of $120 and decide to exercise this option, two transactions will occur.

- You will buy 100 shares of that stock at $120/share

- The party that is short that particular option will be assigned, and forced to sell 100 shares at $120, leaving a short position of 100 shares in their account.

Why may an investor consider exercising a long call contract?

Let’s say that the price of the underlying on that $120 call is currently trading at $135. If you’re long that call, you could exercise that contract, obtain the long shares for $120, then immediately sell it for its current market price of $135, netting a profit of $15/share. That $15 is also known as the option’s “intrinsic value”. Let’s go over what this term means next.

Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value in options trading is the difference between the current price of a stock and the strike price of the option. Only in-the-money options have intrinsic value. This value represents the benefit of buying (calls) or selling (puts) shares of stock at the options strike price rather than the current stock price.

Here’s are the details of our trade above.

Call Strike Price: $120

Current Stock Price: $135

Intrinsic value: $15

If we exercise our long call, we will purchase the shares $15 below the market price, which is obviously advantageous. But is this the most profitable way to cash in on our option? Absolutely not. In fact, we’ll be giving money away. Let’s next learn about extrinsic value to determine why.

Extrinsic Value

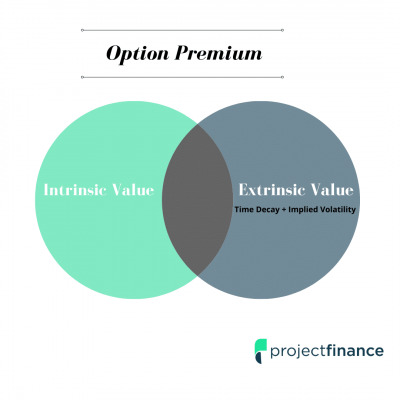

All option values are composed of intrinsic and/or extrinsic values. Extrinsic value (implied volatility + time decay (theta) is the difference between the market price of an option and its intrinsic value. In other words, it’s everything that’s “leftover” from intrinsic value.

The below visual illustrates the different components of an option’s value.

Not all options have intrinsic value. Actually, the value of out-of-the-money options is all extrinsic value. Out-of-the-money options generally do not pose an assignment risk. Why? Let’s revisit our above example but with a different underlying stock price of $110.

Call Strike Price: $120

Current Stock Price: $110

Intrinsic value: 0

If you are long that $120 call and decided to exercise your option, you would buy 100 shares of the underlying stock at $120. Does this make sense? No! You just threw away $10/share. Why not just buy the stock for $10 cheaper in the market for $110?

Since the long party won’t exercise out-of-the-money positions, the short party should therefore have little, if anything, to worry about regarding assignment risk.

Why In-The-Money Options Are Rarely Exercised

But in truth, even in-the-money options are rarely exercised. Why? It makes more financial sense for an investor to simply sell their option contract in the open market rather than convert it to shares. Once you understand why it often doesn’t make sense for a long holder to exercise their contract, it should give you more peace of mind on your short position being assigned.

In order to understand this, we are going to switch over to the tastyworks platform and look at a few examples, starting with exercising a long call.

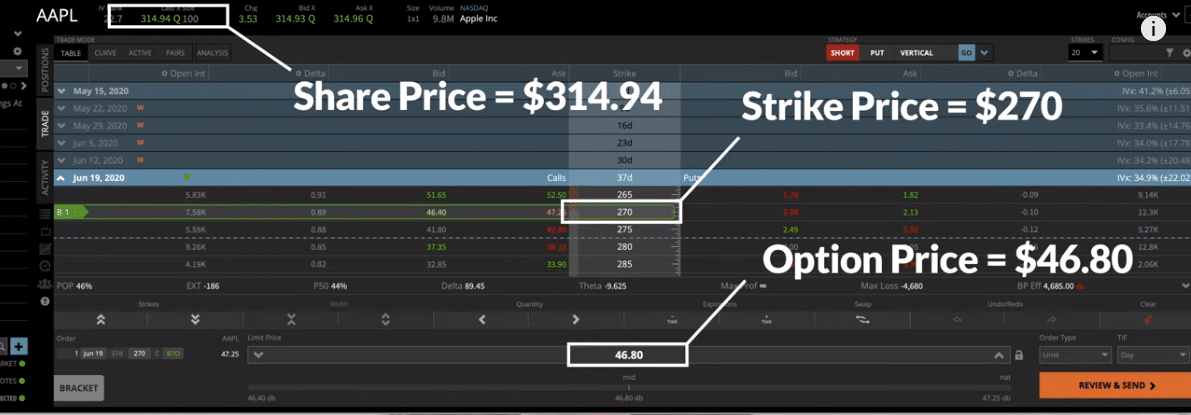

In this example, we are looking at a deep-in-the-money 270 call on Apple (AAPL) which we paid 25 ($2,500) for. Here are the details of the trade:

AAPL Stock Price: $314.94

Call Strike Price: 270

Initial Price Paid for Call: 25 ($2,500)

Option Market Current Value: 46.8 ($4,680)

Intrinsic Value: 44.94 ($4,494)

Now right off the bat, we’re going to take notice that the intrinsic value of the option (44.94) is smaller than the call option’s current market price (46.80). This should be a red flag right away concerning exercisement – keep that in mind.

So let’s say we decide to exercise our 270 AAPL call option and immediately sell the stock received to lock in our profit. Here are the details of this transaction:

Exercise 270 Call: Buy 100 shares at $270/share for a cost of $27,000

Sell Stock: Sell 100 shares of AAPL stock at $314.94/share and receive $31,494

Net Credit Received (profit): $31,494 – $27,000 = $4,494

Net Profit Made: $4,494 – $2,500 (initial debit paid) = $1,994

So the net credit received on this position from exercising our option is $1,994. Not bad, but you could have done better!

Selling a Long Call in the Open Market

Let’s back up a bit here. Remember the current value of the options contract? It is trading at $46.80, the monetary value of which is $4,680. Our net proceeds from exercising the call were only $4,494. See the problem?

We would have netted $186 more ($4,680 – $4,494) had we simply sold the option outright!

Net Profit From Exercising Call: $1,994

Net Profit from Selling Call in the Market: $2,180

So why the discrepancy in selling vs exercising?

Understanding What We Learned

Earlier, we talked upon extrinsic and intrinsic value. Together, these two values comprise an option’s entire premium.

Remember the intrinsic value of our call option above was 44.94 and the current market price of that option was 46.80? Since an option’s value is either intrinsic or extrinsic, we can determine that the extrinsic value of this option is 46.80-44.94 = 1.86.

We touched earlier on this number above; $186 was the additional premium we would receive if we sell the option in the open market. This number is also always synonymous with an option’s extrinsic value.

When you exercise an option with extrinsic value, you are forfeting that additional premium. This premium is comprised of implied volatility and future time value, or, the derivatives extrinsic value.

Dividend Risk: Exceptions to the Rule

Not covered yet in this article is something called “dividend risk”. Options traders must monitor their short call positions closely for any dividend being paid out on the underlying. Why? Option contracts don’t receive a dividend. Therefore, investors long in-the-money call options will likely exercise their contract in order to receive the shares, which do indeed pay a dividend.

If this dividend is greater than an options extrinsic value, short in-the-money call positions will likely be assigned in the days leading up to the ex-dividend date. If you have a tastyworks account, you can always call their trade desk and ask a pro about your chances of being assigned.

Final Word

When you exercise an option early, you are very likely to forego any additional extrinsic value. It is because of this that short options with a lot of extrinsic value are rarely assigned.

This doesn’t mean, however, short options are never assigned. If you are short a very deep-in-the-money call or put option in the days leading up to expiration, the extrinsic value will decay and there is a good chance you will be assigned. In fact, it has been estimated that just over 10% of all option contracts will be exercised, and thus assigned, in their lifespan.

Additionally, if you fail to trade out of your short-in-the-money option before assignment, you will get assignment 99.999% of the time.

Next Lesson

projectfinance Options Tutorials

Additional Resources

Mike Martin

New to options trading? Learn the essential concepts of options trading with our FREE 160+ page Options Trading for Beginners PDF.