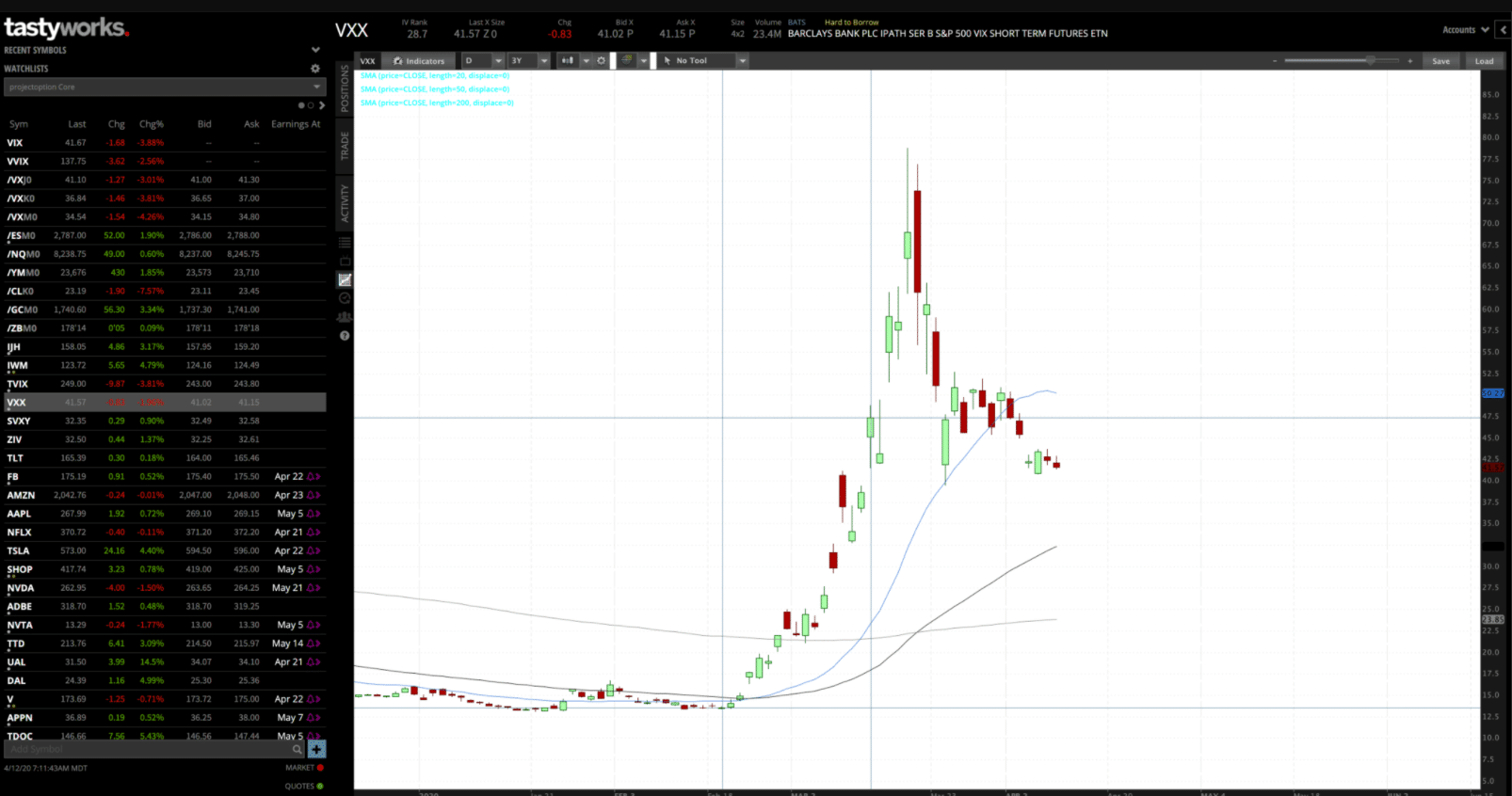

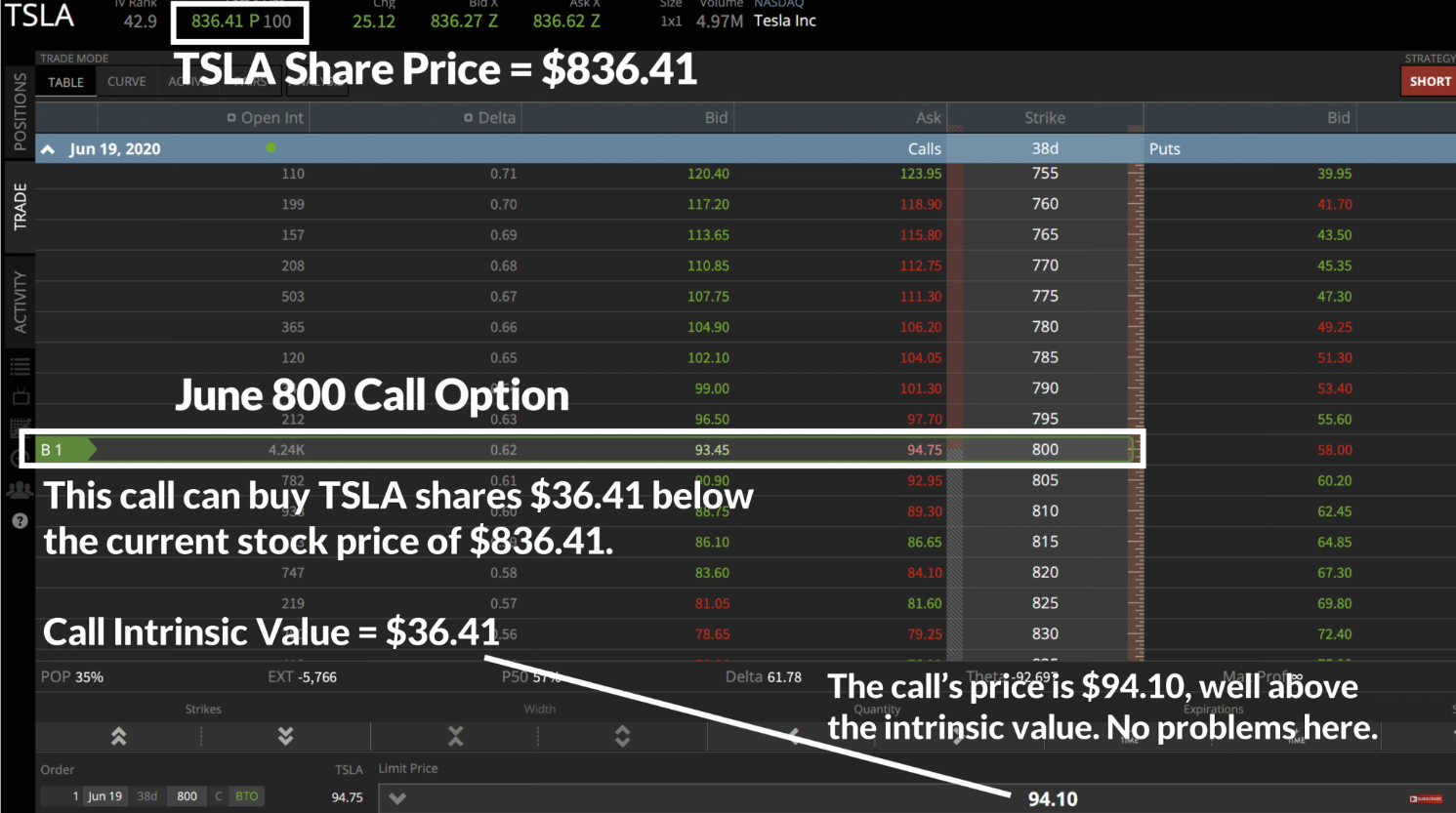

Above is an image of the tastytrade trading platform with the chart page opened up. I know it can be an intimidating thing to look at as a beginner, but there will be a learning curve with any platform you choose. It takes time to learn any new software.

So to familiarize you a little right now, let’s walk through different things that are shown in the image. On the left-hand side, there’s a watchlist for stocks/futures/indices you want to keep an eye on, and you can customize it as you wish.

The main panel depends on which stock you have selected at the time. In the above image, we can see that IWM is selected. On the top of the screen, it’ll show all the information about the bid price, ask price, volume, etc. We’ll discuss what these are later in the blog.

There are a couple more pages as well such as the Trade page which shows the option chain and all the expiration cycles of the options on the stock you’ve selected.

Bid & Ask Price

Every stock, future, ETF and option, all have a bid price and an ask price. The bid price basically means the highest price somebody is willing to pay for something.

In options trading, it is the highest order price for traders that are buying or the highest price a trader is willing to pay. This is the price you get when you sell an option/stock/future.

The ask price, on the other hand, is the lowest order price for traders that are selling, meaning the lowest price a trader is willing to sell something for. This is the price at which you buy an option.

And the difference between the bid and the ask price is called Bid-Ask spread. So for example, the bid price for an IWM share is $134 and the ask price for the same is $134.07, the difference of $0.07 between the two is the bid-ask spread.

This is important because the wider a bid-ask spread is, the more money you’ll lose from simply entering and exiting that trade. The technical term for this is “slippage.”

A thing to be noted is when trading options, you’ll be paying 100x the slippage since an option can only be converted into 100 shares of stock. For instance, if an option has a $0.05 bid/ask spread, then it technically means you’d lose $5 from buying at the ask and selling at the bid. If you buy an option at the asking price of $1.05 and sell it at the bid price of $1.00, you’ll lose $0.05 on the option trade, but that $0.05 actually represents a loss of $5.

Another term to know is “mid-price.” The mid-price is the midpoint between the bid and ask. Typically when you’re trading options, you’d want to try and fill your trades at or near the mid-price.

However, in most cases, you might not get filled on your trade at the mid price right away and therefore you might have to adjust your order to a slightly more unfavorable price.

Option Volume & Open Interest

Volume is the number of shares or contracts that have traded today. In tastytrade, we have two specific columns, one for volume and another for open interest.

Option volume is important to look at especially if you’re a beginner or buying an option on a stock you’ve never traded before.

Open interest is different from option volume. While option volume tells us the number of contracts traded today, option interest is the total number of open option contracts between two parties. If I buy 100 call options as an opening trade, and the counterparty sells those 100 contracts to me as an opening trade (they shorted the options), then open interest increases by 100.

If I sell 50 of those options (closing trade), and the counterparty buys 50 options as a closing trade as well, then open interest decreases by 50.

You don’t need to get caught up in the specifics, but higher open interest basically means there is more trading activity going on with those options, which is a good thing.

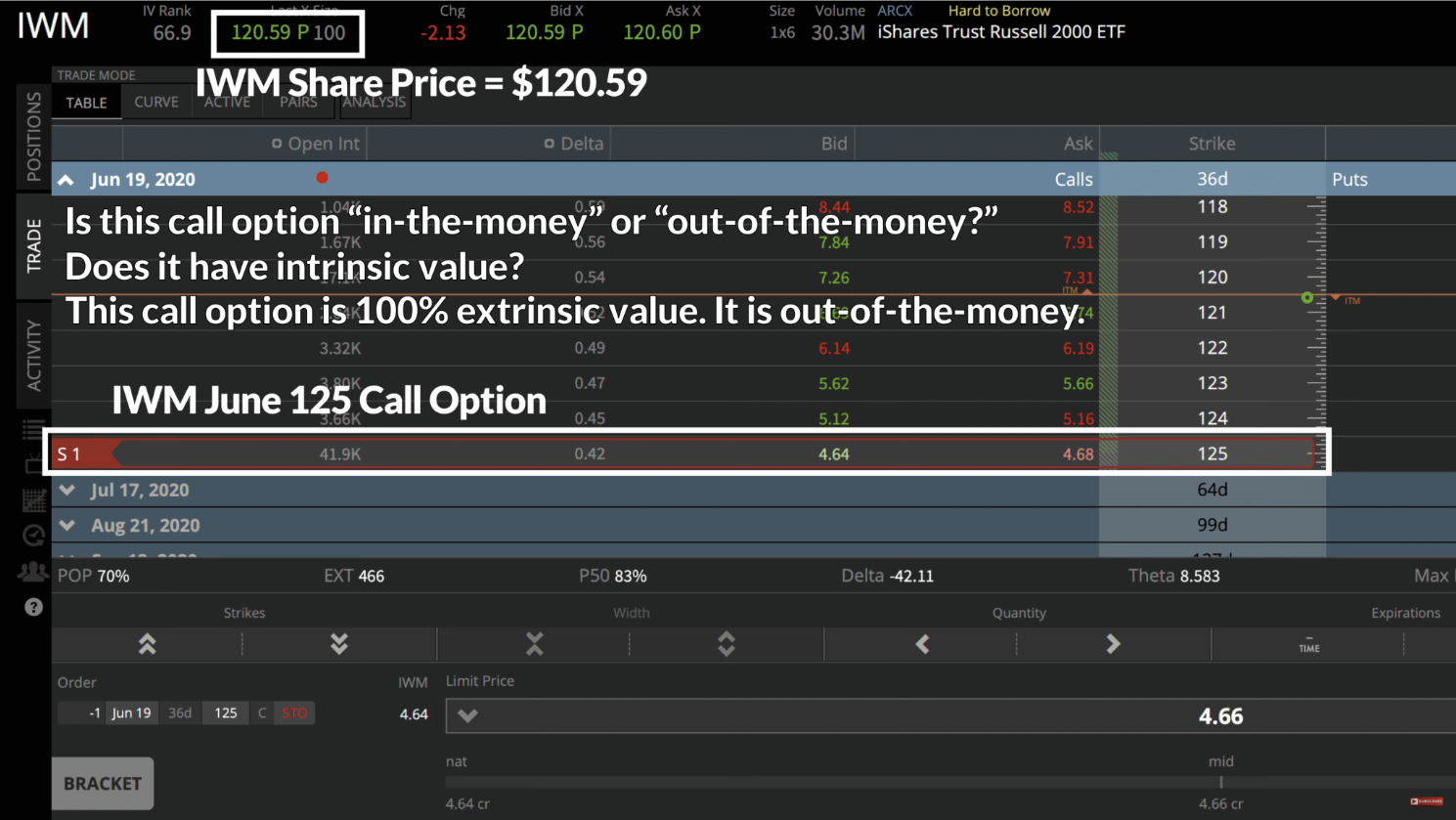

As you can see in the picture above, the open interest in IWM for the June 130 call option is 47.8k, while the option volume meaning options traded today are just 1.06K.

In a nutshell, open interest is the total number of contracts between all the traders in a particular option, and option volume is how many of those contracts traded today.

A thing to remember is that the stocks with high volume will have a narrower bid-ask spread as compared to those with low volume.

Buying options

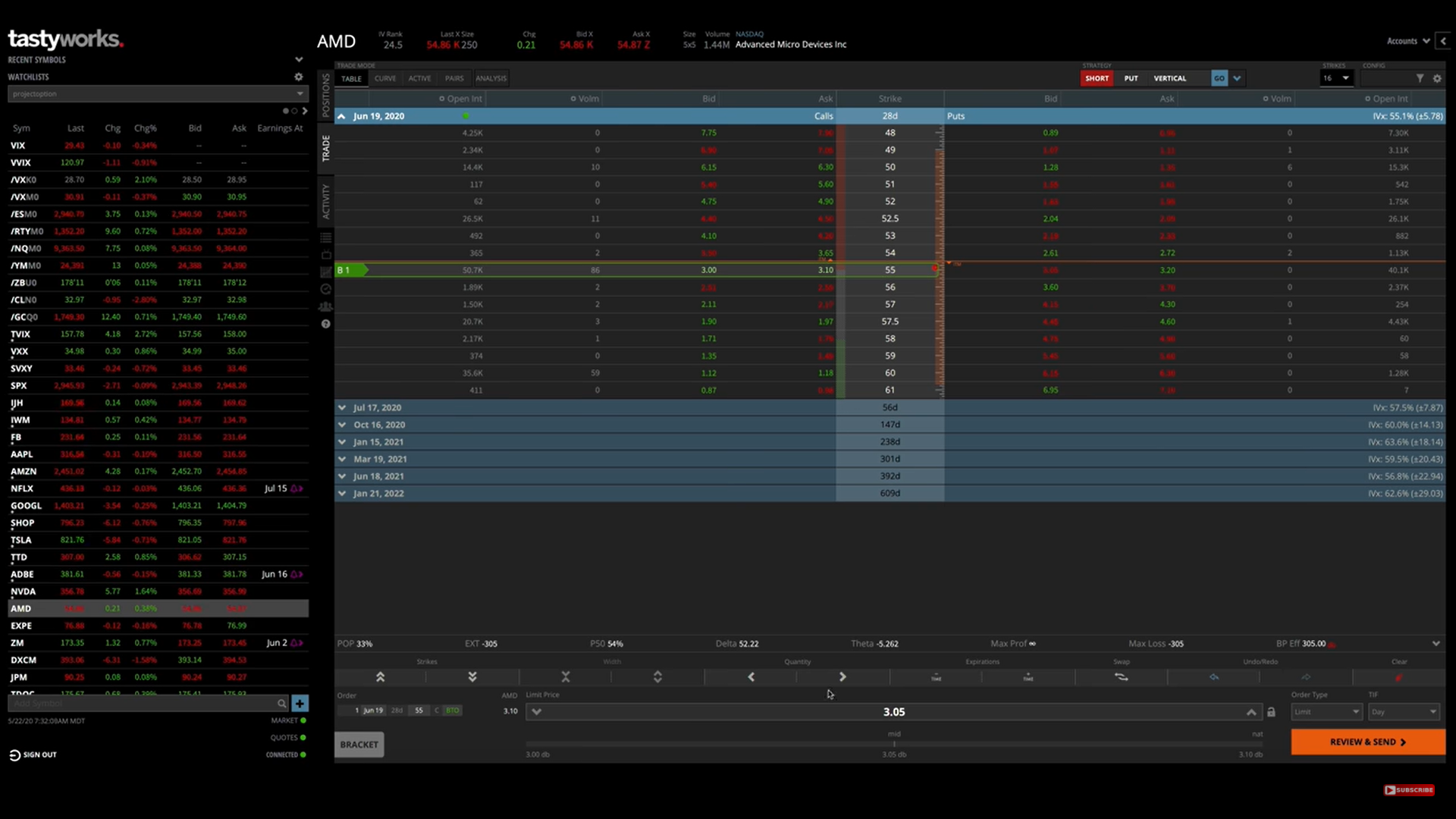

Now that you understand bid and ask price, and what option volume and open interest are, it’s time to finally see how you can buy different options or short them. For this example, we’ll perform all four basic trades in AMD.

Buying Calls

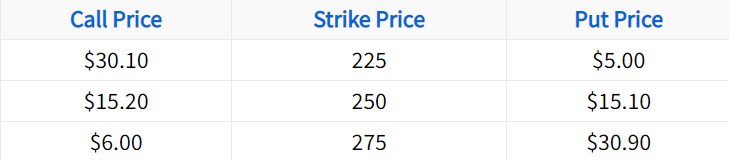

So as you can see above, the bid and ask prices for the June 55 call in AMD right now are $3.00 and $3.10 respectively. When we try to buy an option, our goal will be to get it at mid-price which, in this case, that is $3.05.

All you have to do to place an order in tastytrade is click on the “ask price” of the option you’d like to buy and it’ll bring up an order to buy the option at the bottom of the screen, automatically at the mid-price.

As you can see below, when we clicked on the June 55 call option in AMD, it brought up the order window at the bottom of the screen. All you have to do now is click “Review & Send.”

When you “Review & Send” the order, it’ll show you another window that confirms all of the trade’s details for you, including the fees and change to your buying power, which is how much money you have available to allocate to trades.

Buying Puts

The process for buying a put is exactly the same as buying calls, except instead of clicking on “ask price” on the left-hand side of the screen i.e. in the calls section, you do it in the puts section on the right-hand side. (See the image below to see how two sections are divided in tastytrade by the Strike column)

Shorting Options

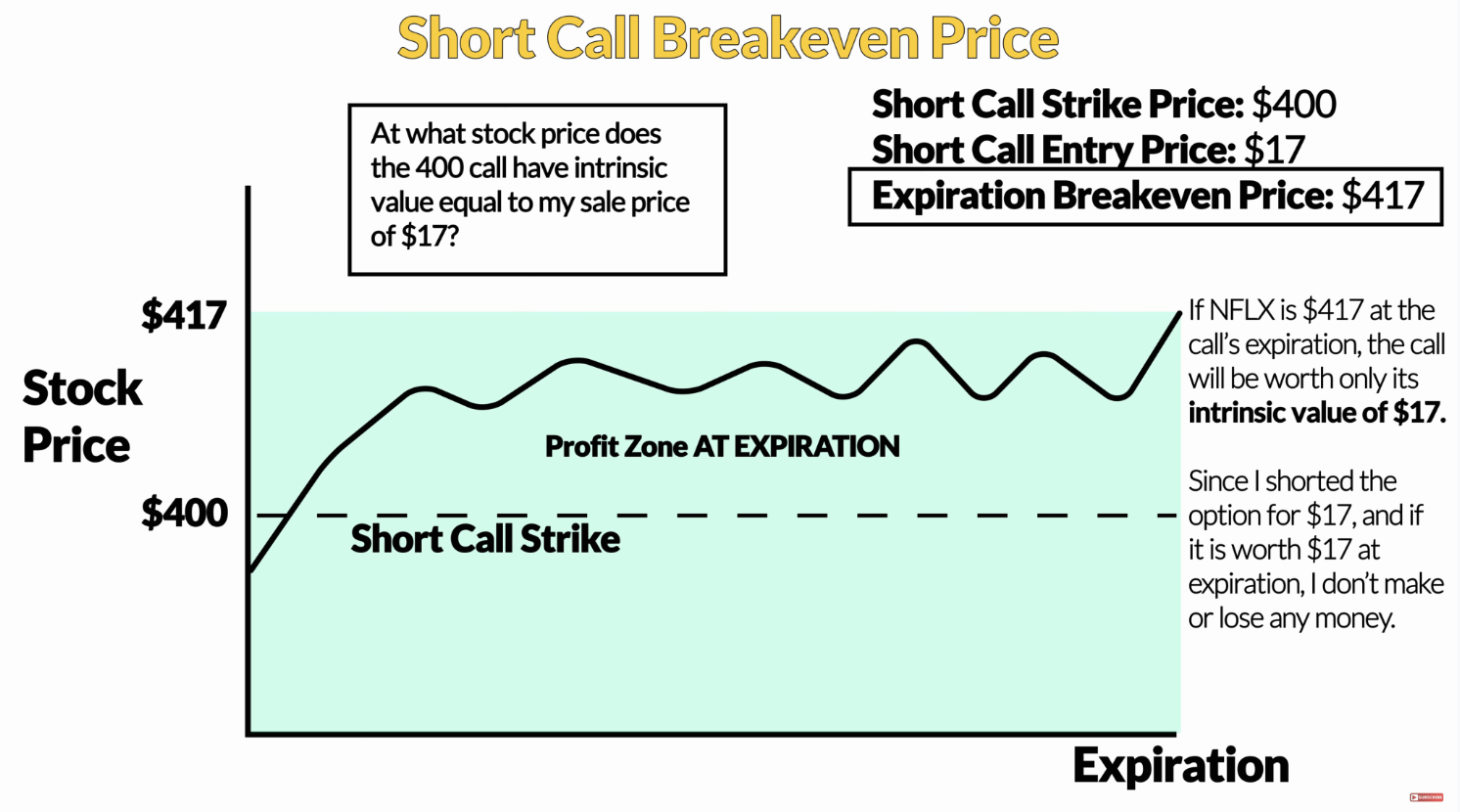

Shorting Calls

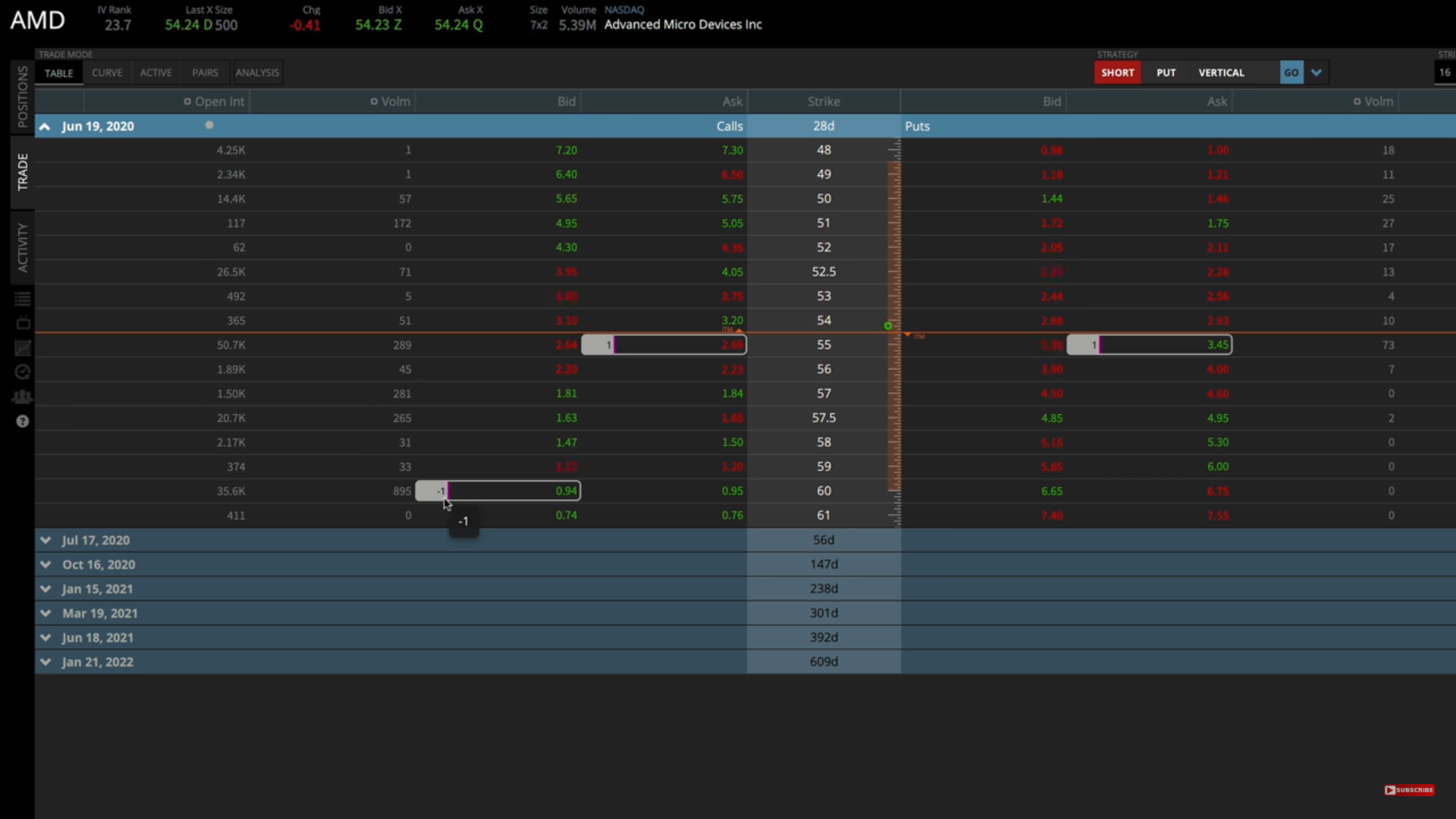

To short an option, meaning to sell an option that you don’t own (betting against the option price from increasing), click on the bid price for the specific option you want to short.

After clicking on the bid price, the order will merely be set up, but you won’t have shorted the option just yet. You’ll need to click Review & Send, and then confirm all the trade details.

After shorting one option, you will see a “-1” next to the option on the option chain, indicating you’ve shorted one of those options. On options you’ve purchased, there will be a positive number next to the option’s price on the option chain.

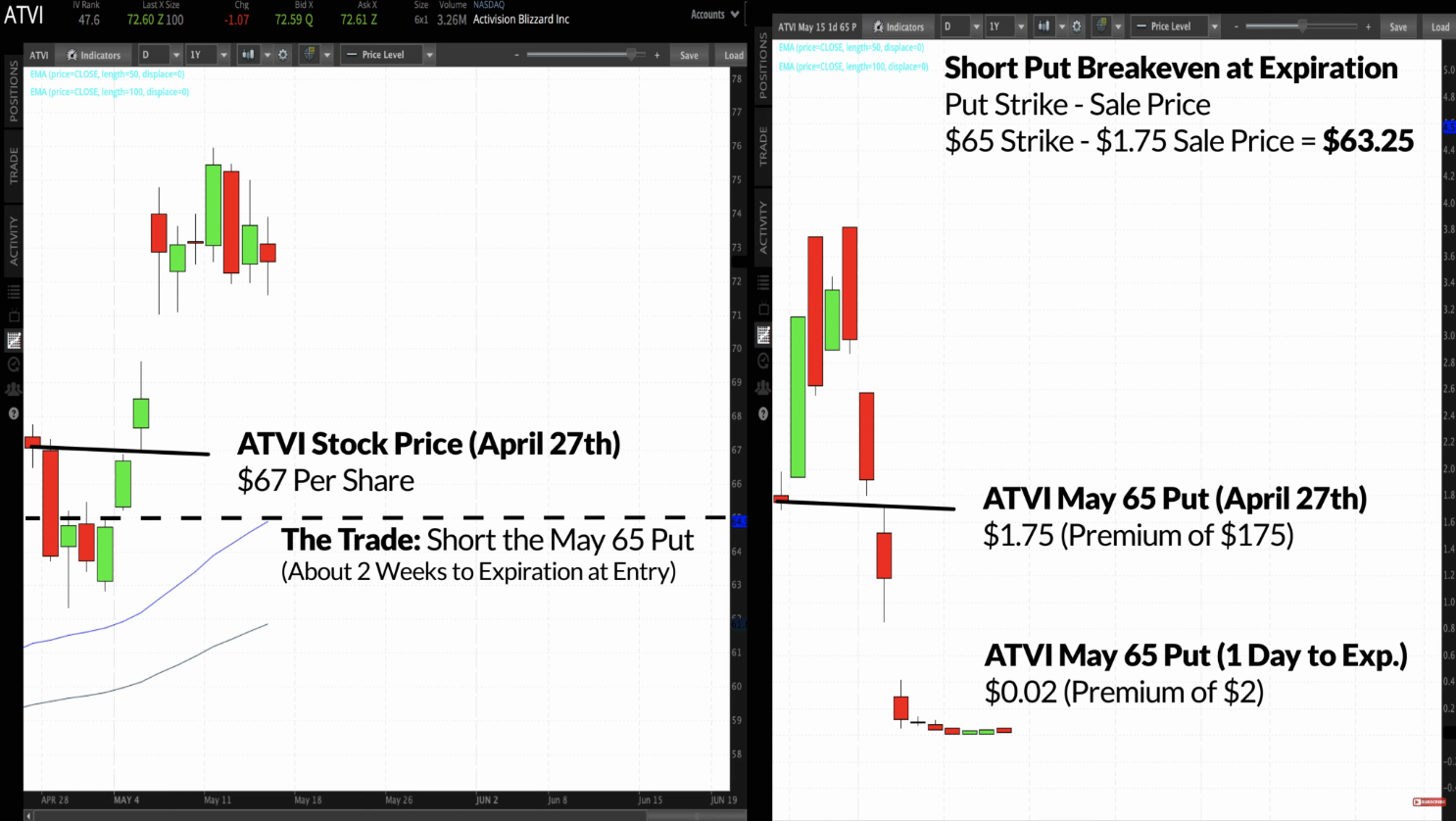

Shorting Puts

As you would have guessed by now, instead of clicking on the “bid price” on the call side of the screen, you click on “bid price” on the put side of the screen, just as we did at the time of buying puts and everything else remains exactly the same.

Closing Options

Closing an option refers to when you close your position and exit the trade by selling or buying back the option, making a profit or loss in the process.

There are two ways you can close an option. First, by directly right-clicking on the option in your positions tab and then clicking “Close Position,” as shown in the image below. Or you can do it manually from your main panel.

The way you do it manually is by executing the opposite trade of what you did earlier. So in the case of purchasing an option, you simply sell it to close the trade. And if you shorted an option, you buy it back to close the trade.

So if you buy an option as your opening trade, your closing trade is selling that same option.

If you short an option as your opening trade, your closing trade is buying back that same option.

The next step from here would be to learn more about options trading before you put lots of money into it. A great resource would be this blog along with our YouTube channel, which already has a lot of content and a family of hundreds of thousands of aspiring options traders, just like you. Be sure to check that out as well.