Last updated on February 10th, 2022 , 07:11 pm

An option’s delta represents the directional risk component of an option position, or its exposure to changes in the underlying stock price.

Delta is the option Greek that measures an option’s directional exposure, as delta is used to estimate an option’s expected price change with $1 changes in the price of the stock.

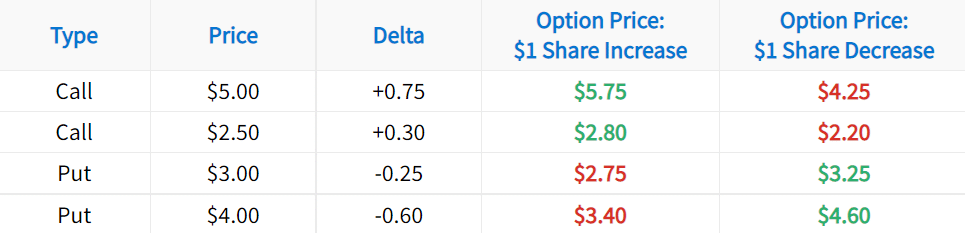

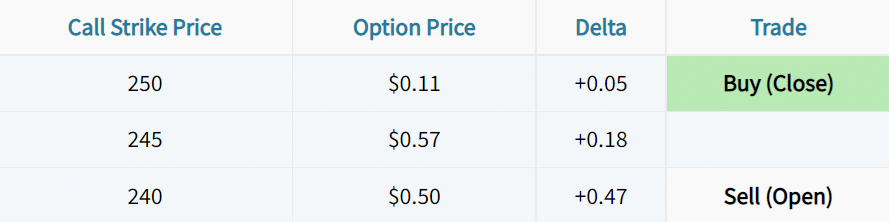

To illustrate what this means, let’s look at a very basic example. In the following table, pay attention to how each option’s delta predicts the option’s price in each scenario:

The table above demonstrates the application of delta to assess an option’s expected price change:

➜ To estimate an option’s price after a $1 increase in the stock price, add the option delta to the option price.

➜ To estimate an option’s price after a $1 decrease in the stock price, subtract the option delta from the option price.

You’ve learned the basics of what an option’s delta represents! Now, let’s dive a bit deeper and discuss the differences between the deltas of calls and puts.

Call Option Deltas vs. Put Option Deltas

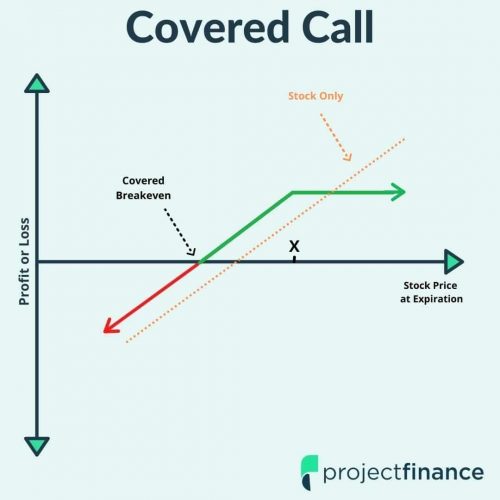

So, you know the basics of what delta represents, but now it’s time to learn about the differences between call and put deltas. As you may have noticed in the table from the last section, the call deltas are positive, and the put deltas are negative. More specifically:

➜ Call deltas are positive, ranging from 0 to +1

➜ Put deltas are negative, ranging from -1 to 0

In general, this means:

➜ When the stock price rises, call prices are expected to increase and put prices are expected to fall.

➜ When the stock price drops, call prices are expected to fall and put prices are expected to increase.

As a result, traders who buy call options or sell put options benefit from stock price increases. On the other hand, traders who sell call options or buy put options benefit from stock price decreases.

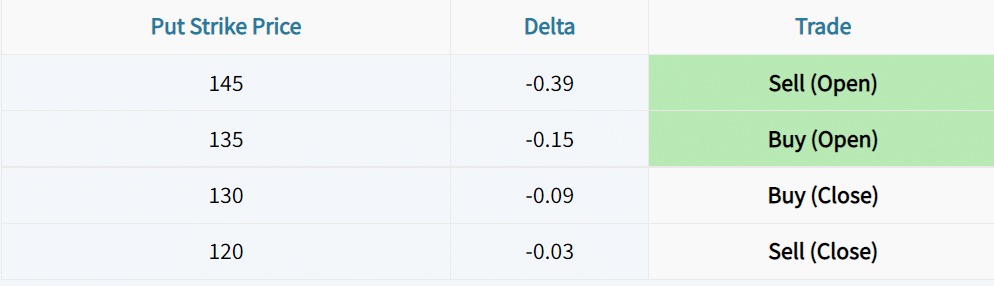

With that said, let’s visualize these concepts with some real data. First, we’ll analyze call option prices. Then, we’ll analyze put option prices.

Call Option Price vs. Stock Price Changes

As an illustration, we analyzed the price changes of a call option traded on SPY. Here are the specifics:

Stock: S&P 500 ETF (ticker symbol: SPY)

Time Period: January 29th, 2016 to March 18th, 2016

Option: March 195 Call

Let’s take a look! In particular, pay attention to the relationship between the price changes of SPY and the call option:

As shown here, there is a strong relationship between the price changes of the stock and the call option. A call’s positive delta expresses the direct correlation between the stock price and the call price.

Next, we’ll look at the same example, except we’ll swap out the call option with a put option.

Put Option Price vs. Stock Price Changes

In this example, we’ll visualize the price changes of the March 200 put on SPY.

In particular, note the correlation between the price changes of SPY and the put option.

As illustrated here, the put option’s price is inversely related to changes in the price of SPY shares. A put option’s negative delta expresses the inverse correlation between the stock price and the put’s price.

Using Delta to Measure Directional Risk

Now, it’s time to learn about how an option’s delta value represents its price sensitivity relative to movements in the stock price.

As mentioned earlier:

➜ Call deltas are positive, ranging from 0.0 to +1.0

➜ Put deltas are negative, ranging from -1.0 to 0.0

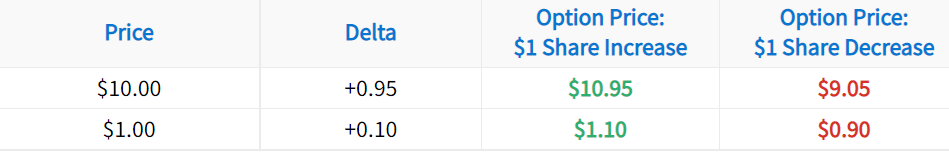

Consider the following call option positions:

Now, let’s compare the sensitivity of these positions:

➜ The call option with a delta of +0.95 is expected to experience a price change of ±$0.95 with a $1 change in the stock price.

➜ The call option with a delta of +0.10 is expected to experience a price change of $0.10 with a $1 change in the stock price.

Consequently, a call option with a delta of +0.95 has almost ten times more directional risk than a call option with a delta of +0.10. The same concept applies to put options. As an illustration, let’s visualize the sensitivity of call and put options with various delta values.

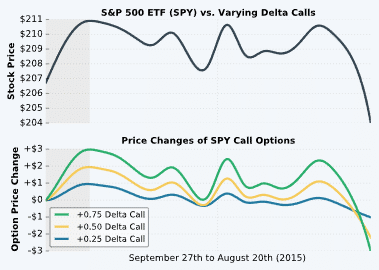

Visualizing Call Option Price Sensitivity

First, let’s start with the setup for this example:

Stock: S&P 500 ETF (ticker symbol: SPY)

Time Period: September 27th, 2015 to August 20th, 2015

Expiration: August 21st, 2015

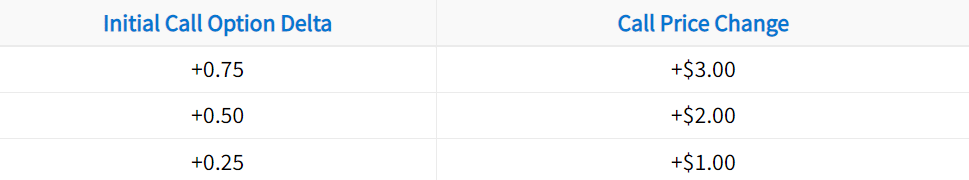

To visualize the price changes of SPY call options with different deltas, we analyzed three separate call options with deltas of +0.25, +0.50, and +0.75, respectively. When examining this visual, notice how each option’s delta translates to its degree of price sensitivity:

In the highlighted area, SPY experienced a $4 increase in its price. How did each call option’s price respond?

In the example above, the option’s delta was very accurate. However, it’s important to note that it won’t always work so perfectly, as all of the option Greeks are theoretical values that come from option pricing formulas. Nevertheless, the option Greeks tend to be fairly accurate.

Next, we’ll run through the same example, except this time we’ll be analyzing put options.

Visualizing Put Option Price Sensitivity

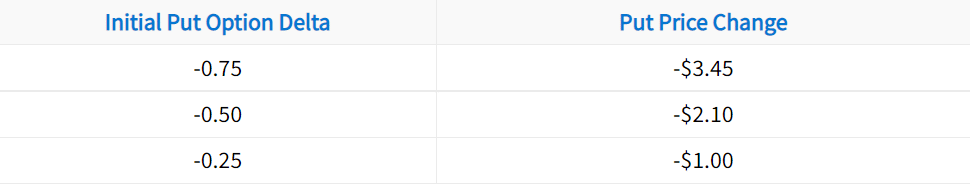

To analyze put option price sensitivity based on the option’s delta, we’ll use the same stock, time period, and expiration cycle as before. However, we’ll analyze three separate SPY put options with deltas of -0.25, -0.50, and -0.75, respectively.

In the highlighted area, SPY experienced a $4 increase in its stock price. How did each put option respond?

In the visual example, the put option with a delta of -0.50 had an actual price change of -$2.10 relative to a $4 increase in the stock price. A $2.10 price change was only $0.10 away from the projected price change based on the option’s delta. Very impressive!

In the last section, we’re going to quickly discuss one of the major factors that determine an option’s delta.

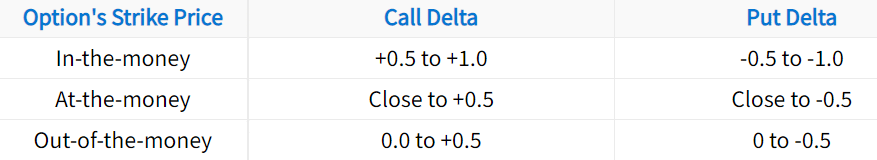

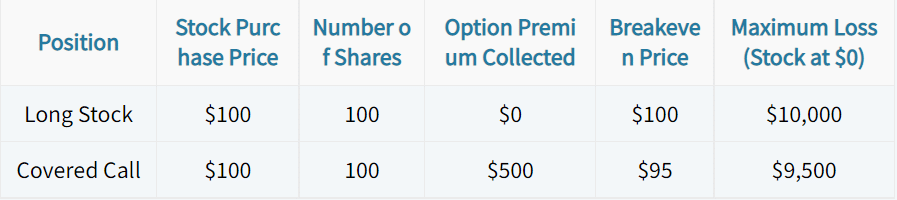

Option Strike Price vs. Delta

In this final section, we’re going to quickly discuss one of the major factors that determine an option’s delta: the strike price of the option relative to the stock price. Here’s a quick guide to in-the-money, at-the-money, and out-of-the-money options:

In-the-money: Call options with a strike price below the stock price; Put options with a strike price above the stock price.

At-the-money: A call or put option with a strike price equal to or near the stock price.

Out-of-the-money: Call options with a strike price above the stock price; Put options with a strike price below the stock price.

Most of the time, options in each of these categories have deltas in the following ranges:

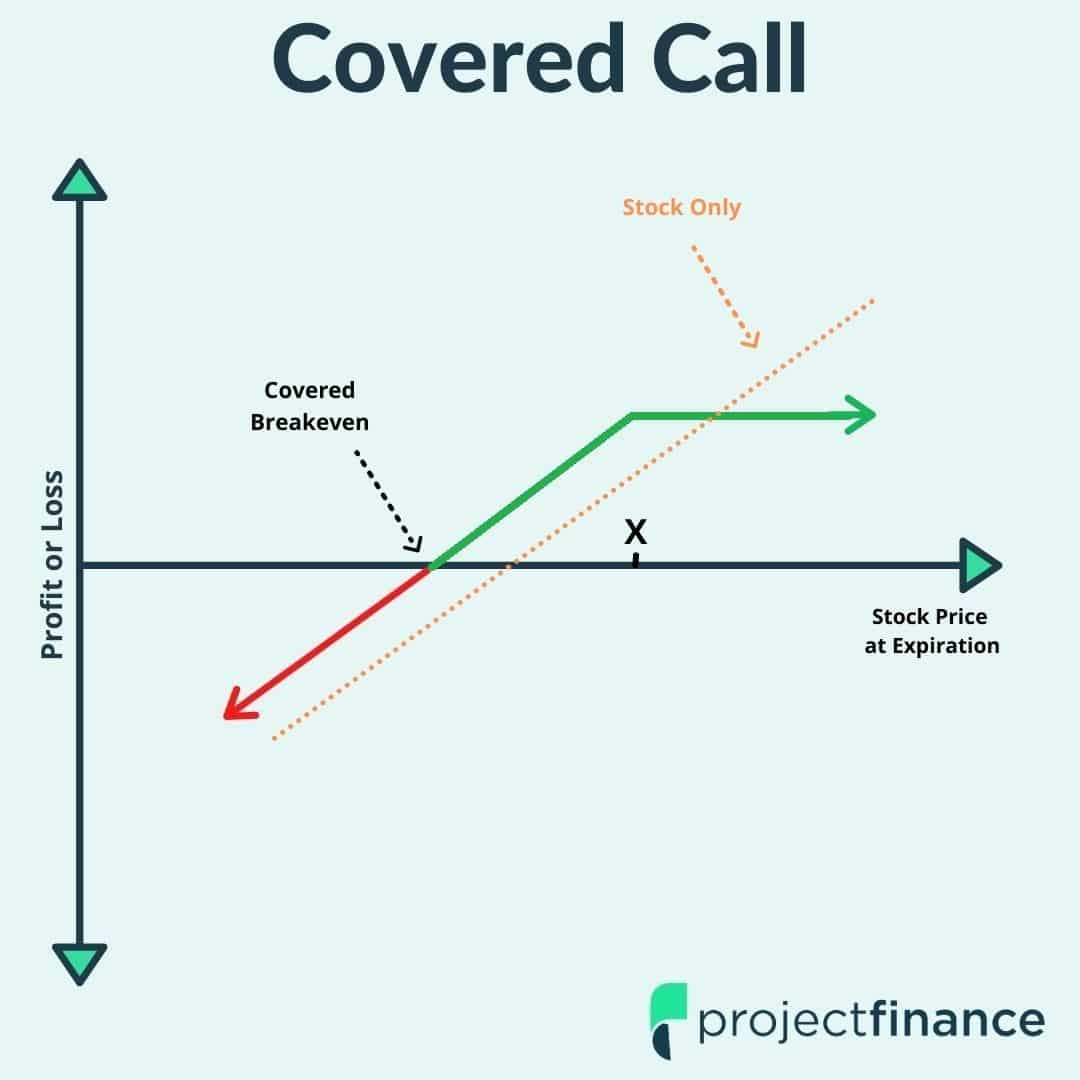

The following visual serves as a visual representation of the table above:

At strike prices lower than the stock price, call deltas are closer to +1, and put deltas are closer to 0. At strike prices near the stock price ($207), option deltas are close to ±0.5. At strike prices above the stock price, call deltas are closer to 0 and put deltas are closer to -1.

As an options trader, you have full control over the strike price you trade.

When trading in-the-money options, you will have more profit/loss exposure when the stock price changes.

When trading out-of-the-money options, you will have less profit/loss exposure when the stock price changes.

Additional Resources