Last updated on March 14th, 2022 , 06:35 pm

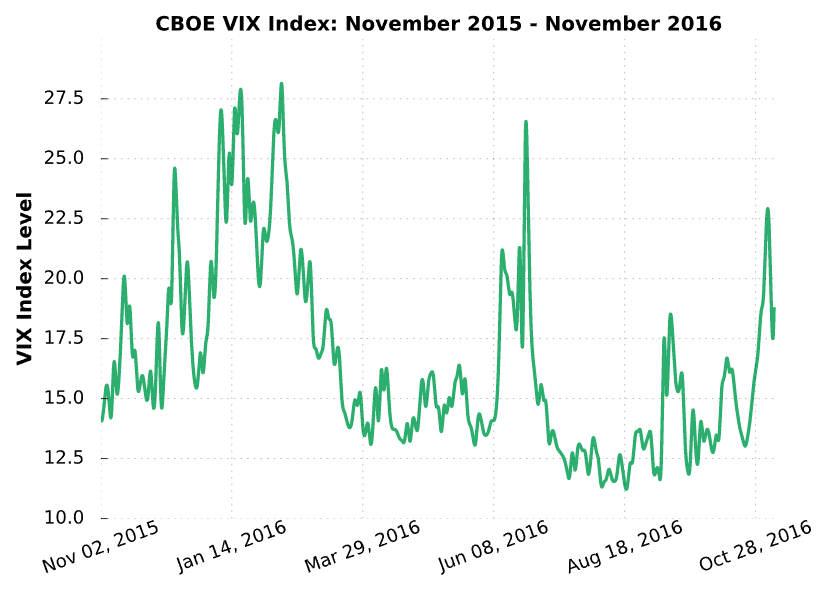

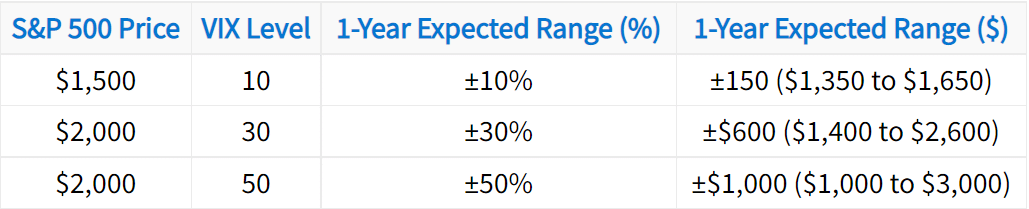

The Cboe VIX Index measures prices of 30-day option prices (implied volatility) on the S&P 500 Index. Since option prices are an indicator of fear or complacency in the marketplace, the VIX is sometimes viewed as a “fear index” that gauges the level of uncertainty in market participants.

As mentioned in our guide on the VIX Index, the VIX cannot be traded directly, but there are products that allow traders to gain exposure to changes in the VIX Index. VIX futures are one of the products available when trading volatility.

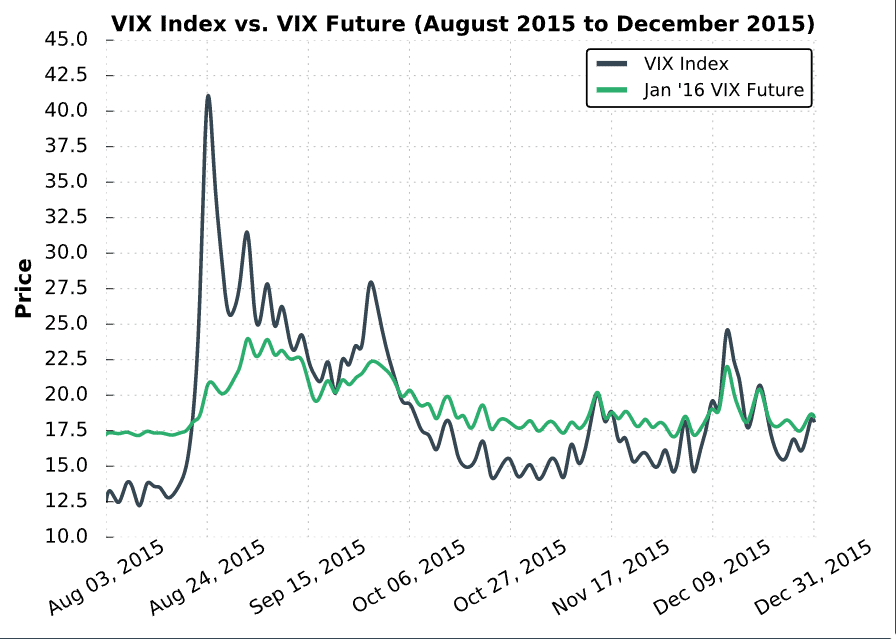

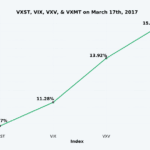

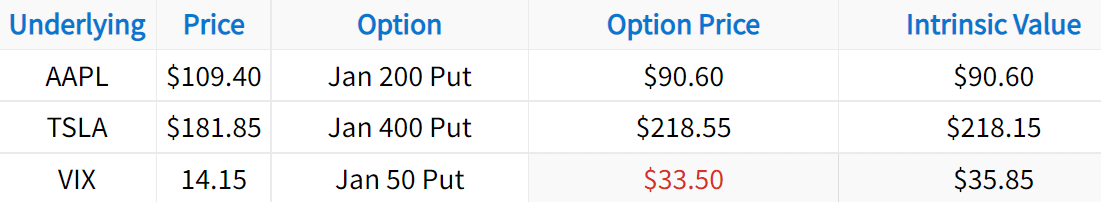

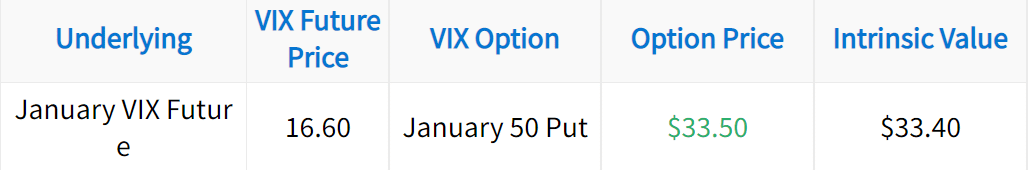

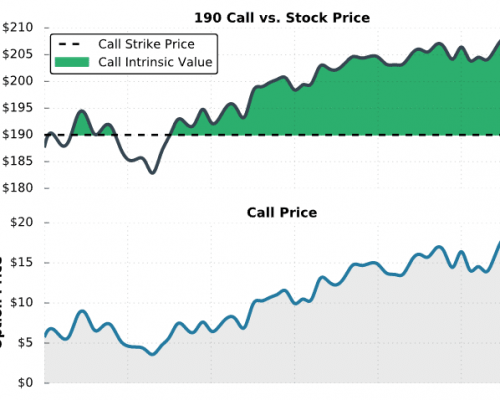

The following visual demonstrates how a future on the VIX can change relative to the VIX Index:

As we can see here, the price of the VIX futures contract changes in the same direction as the VIX Index, but not by the same amount in this case (we’ll discuss this in-depth shortly).

VIX Futures Contract Characteristics

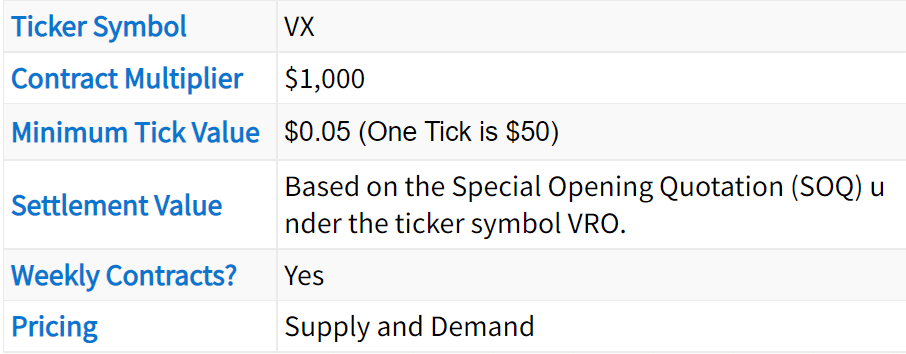

Before discussing the most important things to be aware of when trading VIX futures contracts, let’s go over the basic characteristics of each contract.

Perhaps the most important aspect to be aware of when trading VIX futures is that the contract multiplier is $1,000, which means each point change in the contract is equal to a $1,000 change in value.

For example, if a trader buys one contract at 15 and sells the contract at 16, the profit on the trade is $1,000. Conversely, if a trader buys a contract at 20 and sells the contract at 15, the loss on the trade is $5,000.

Because of this, VIX futures are very large contracts that should be traded cautiously, especially since the margin requirement to trade one contract can be as low as a few thousand dollars (the margin will vary depending on the brokerage firm and market volatility).

Another vital point to mention is that the minimum tick value of a VX contract is $0.01, which translates to a bid-ask spread of $0.01. With a contract multiplier of $1,000, a $0.01 tick represents $10 in actual profits or losses. So, a trader would lose $10 by purchasing at the ask price and selling at the bid price, or vice versa (assuming a $0.01 bid-ask spread)

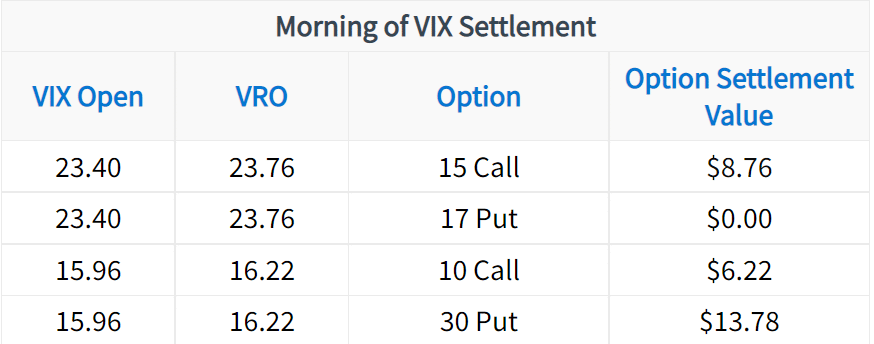

Regarding the settlement value, each VIX futures contract will settle to the value of VRO on the Wednesday morning that is 30 calendar days prior to the subsequent standard S&P 500 Index options expiration. The VRO settlement value comes from a VIX-style calculation on that Wednesday morning.

In terms of the contracts available, weekly contracts have recently been created, but the volume and open interest in the weekly contracts are still extremely low, so trading the standard monthly contracts is far superior to the weekly contracts in terms of liquidity.

Lastly, VIX futures contracts are priced based on the supply and demand of the contracts, which is different from the calculated value of the VIX. So, if the VIX changes in one direction, a future on the VIX might not change at all. In fact, it’s possible for the contracts to move in the opposite direction of the VIX Index. However, as settlement approaches, volatility futures will track the VIX Index much more closely.

Things You Need to Know Before Trading VIX Futures

Before trading a VIX futures contract, these are the most important things you need to be aware of:

1) Longer-term contracts typically have more risk in terms of carrying costs.

2) As a VIX future gets closer to its settlement date, the contract’s price will converge to the VIX Index price, as well as become more sensitive to changes in the VIX Index.

Let’s visualize each of these points by looking at some historical VIX futures data.

VIX Futures Carrying Costs (in Contango)

When holding VIX futures contracts, traders are exposed to profits or losses as the contract converges to the VIX Index.

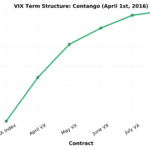

When the VIX is low, the futures contracts tend to be priced higher than the index (referred to as contango). As time passes, the futures contracts will decay in price towards the VIX Index if the VIX doesn’t increase.

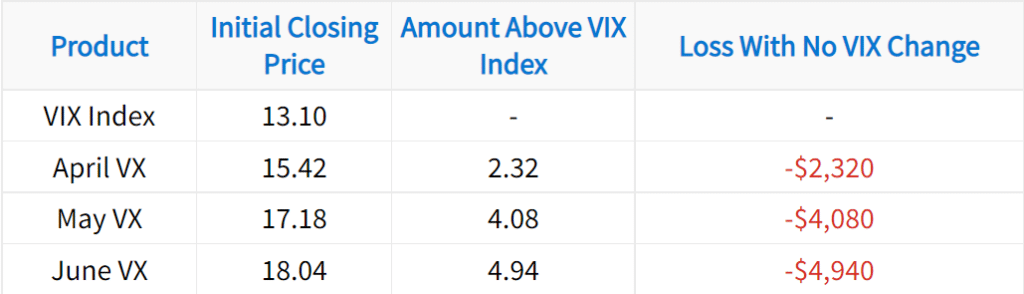

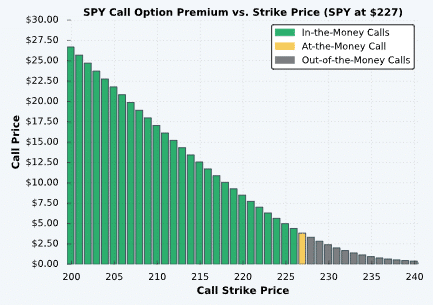

The following visual illustrates the concept of decaying volatility futures contracts as time passes (the dashed lines represent the settlement dates for each respective contract):

Data from Cboe’s Historical VIX Futures Data

At the beginning of the period, each product had the following price and potential loss from purchasing the contract:

The values in this table come from the potential loss when buying and holding a VIX futures contract. For example, if a contract is purchased at 15.42 and decreases to 13.10, the loss will be $2,320. If the contract was shorted at 15.42 and the price fell to 13.10, the profit would be $2,320. However, selling volatility futures has significant risk because the VIX tends to rise very quickly when the market falls (as demonstrated in the previous visual).

So, the next time the VIX Index hits new lows, be wary of buying VIX futures to profit from the inevitable implied volatility expansion. If a volatility trader does not correctly time the increase in the VIX when trading VIX futures, the trader may lose substantial sums of money from the price decay of the contracts when the curve is in contango.

VIX Futures Carrying Costs (in Backwardation)

When the VIX is abnormally high, the futures contracts tend to be priced lower than the index (referred to as backwardation). As time passes, the futures contracts will increase in price towards the VIX Index if the VIX doesn’t decrease.

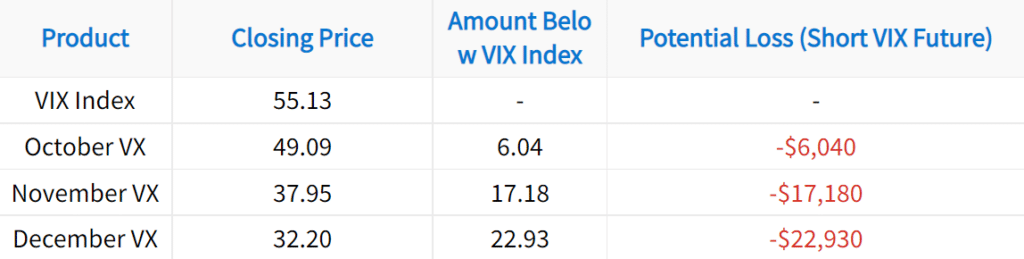

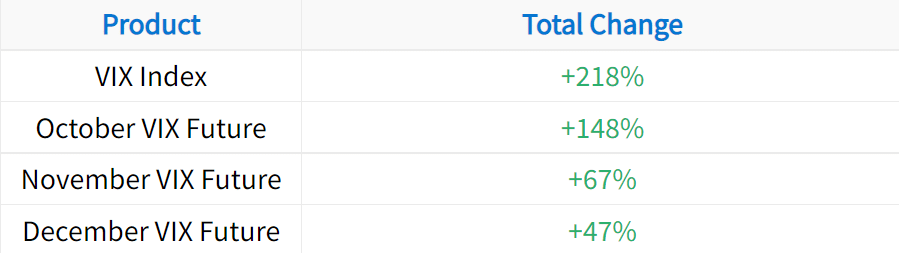

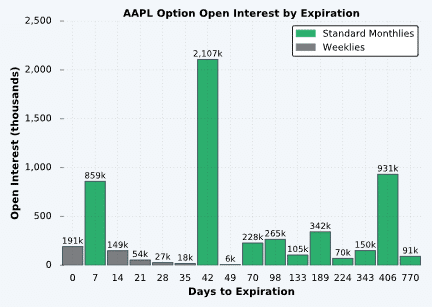

The following visual illustrates the concept of increasing volatility futures contracts as time passes:

Data from CBOE’s Historical VIX Futures Data

As we can see here, when the VIX Index surges, the prices of VIX futures tend to trade at lower prices than the index because the market doesn’t expect the VIX to stay at such elevated levels for long. In this scenario, carrying costs are transferred to the sellers of VIX futures, as increasing contract prices lead to losses for sellers. As an example, let’s look at the closing prices of each product on October 14th, 2008:

So, with the VIX at 55.13 and the December VIX future at 32.20, the December VIX future could increase by 22.93 if the VIX stays at 55.13 through the December contract’s settlement. For a trader who sells the contract, an increase of 22.93 results in a loss of $22,930. Of course, these values turn into profits for the buyers of each contract.

In summary, when the VIX Index reaches abnormally high levels, the VIX futures will often be cheaper than the index. Before selling a VIX future to profit from the inevitable volatility collapse, understand that incorrect timing of the volatility decrease may lead to significant losses due to the gradual increase in the contract’s price.

Additional Resources