Last updated on May 9th, 2022 , 05:18 am

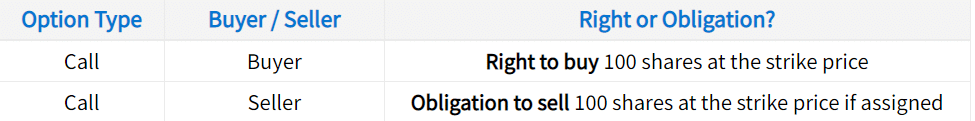

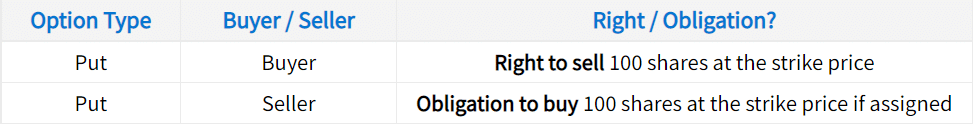

What are options? To give you the textbook definition, options are financial contracts that give the holder (buyer) the ability to buy or sell 100 shares of stock at the option’s “strike price” at or before expiration. The seller (writer) has the obligation to deliver those shares if they are assigned to an option holder’s exercise.

Before you learn about the two option types, let’s go over basic characteristics of options.

Strike Prices & Expiration Dates

Two characteristics that all options have are strike prices and expiration dates. We’ve written entirely separate guides on both, but for now it’s necessary to provide a brief definition of each.

1.) A strike price is the price that shares will be exchanged at if the option buyer exercises, or if the option is in-the-money and held through expiration. For example, if a trader owns a call option with a strike price of $50, the trader will effectively buy 100 shares of stock at $50 per share if they exercise the option (a valuable right to have when the shares are trading higher than $50).

On the other hand, the seller of the call option is obligated to deliver these shares if assigned, effectively selling 100 shares of stock for $50 per share (an unfavorable scenario when the shares are trading for significantly more than $50).

2.) In addition to a strike price, all options have an expiration date, which is the date each option stops trading and ceases to exist. This is one of the major differences between stocks and options. Stocks can be held forever, but at some point, options expire. Prior to expiration, traders with positions must decide whether they want to close their option position, or let it expire.

If a trader lets an option expire in-the-money, they will take on a stock position (unless the options are on a product with no tradable shares, such as the VIX or SPX). On the other hand, options that expire out-of-the-money simply disappear from the account, leaving the trader with any residual profits or losses from the worthless option.

Standard Option Contract Multiplier

The last basic option characteristic you need to know is called a contract multiplier. The real value of an option in dollar terms is the option’s price multiplied by the contract multiplier. A standard equity option contract has a contract multiplier of 100 because each option controls 100 shares of stock.

When you view an option’s price, the actual value of that option is the price multiplied by 100 (for standard equity options). For example, if you want to buy an option that’s quoted at $13.20, you’ll need $1,320 in your account to buy that option (not including commissions).

You’ve just learned the very basics of options. To bring it all together, every option has a strike price and an expiration date. Additionally, standard equity options have a contract multiplier of 100, which means the option’s value in dollar terms is the price multiplied by 100. Armed with this knowledge, it’s time to learn the basics of calls and puts!

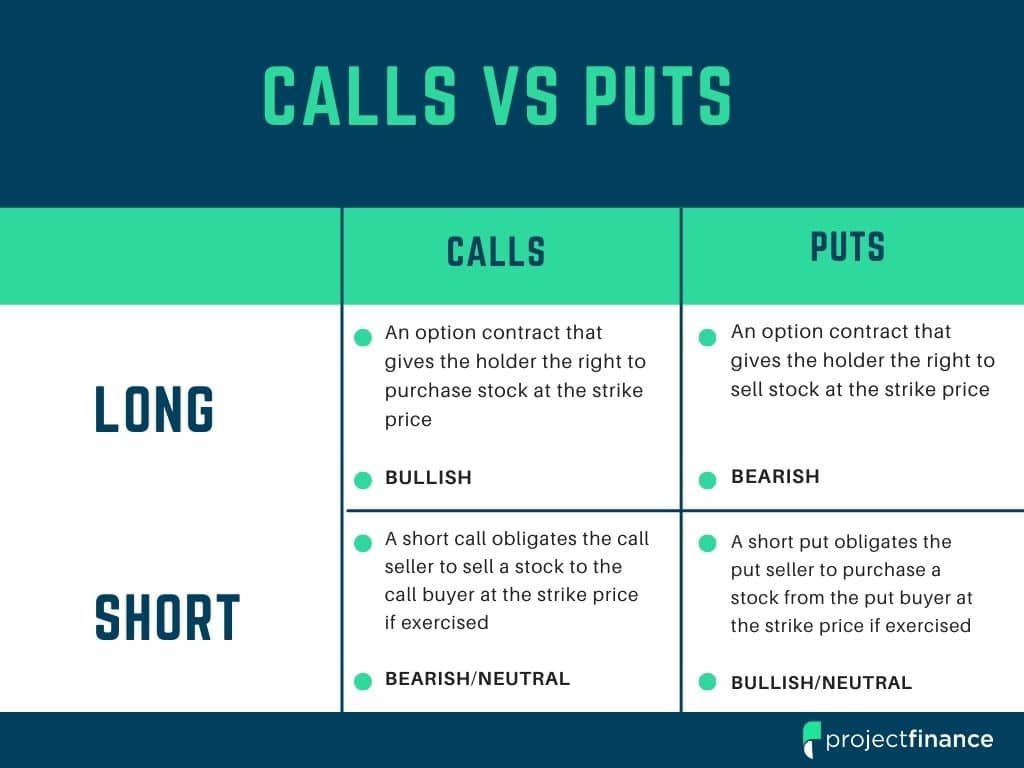

First, we’ll cover call options. Then, we’ll finish with put options.

Call Option Basics

In this section, you’ll learn about call options. In order to accomplish this, let’s discuss calls from both the buyer and seller’s perspective.

Why would someone buy a call? Well, a call buyer benefits when the stock price increases to a price well above their option’s strike price. If the stock price does increase above the call’s strike price, the call option’s price increases, as the ability to buy shares at a much lower price becomes more valuable. Therefore, a trader who buys a call anticipates the stock price will increase.

Conversely, a call seller benefits when the stock price trades below the option’s strike price. If the stock does trade below the strike price, the call’s price will trade towards $0 as expiration approaches. As a result, the call seller will keep the premium (an option’s price is sometimes referred to as premium) they collected for selling the call. If the stock price increases above the strike price, the call seller is in trouble because as the stock price increases, the call becomes more and more valuable. When the option is worth more than the seller collected for it, they will have losses. Therefore, a trader who sells a call option anticipates the stock price will remain below the strike price.

Call Option Trade Example

Now that we’ve gone through both perspectives related to call options, let’s look at a visual example of how a call’s price changes when the stock price changes. In the following chart, we’ll analyze a call option with a strike price of $190. Be sure to compare the stock price to the call’s strike price, and see how that translates to a change in the call’s price.

As illustrated here, when the stock price increases more and more above the call’s strike price of $190, the call option becomes more valuable. Now, if a trader had purchased the call option at the beginning of the period, they would have profits of about $1,500 (because the call is worth $15 more than the trader’s purchase price, and every $1 of an option’s price represents $100 in actual dollar terms).

On the other hand, the call seller would be sitting on $1,500 losses, as the contract is worth $15 more than they sold it for. In this example, the call option’s value increases because the ability to buy shares of stock at $190 gets more valuable as the stock price increases further above $190.

If this call option was held through expiration, a trader who owned the call option would be left with 100 shares of stock, with an effective purchase price of $195 per share ($190 strike price + $5 premium paid for the option). On the other hand, a trader who sold this call option would have -100 shares of stock (a short stock position of 100 shares), with an effective sale price of $195 per share ($190 strike price + $5 premium collected for the option).

Alright, now that you have the basics of call options down, let’s talk about put options!

Put Option Basics

Like we did for calls, let’s discuss put options from both the buyer and seller’s perspective.

Why would someone buy a put? A put buyer benefits when the stock price decreases to a price well below their option’s strike price. If the stock price does drop below the put’s strike price, the put option’s price increases, as the ability to sell shares at a higher price becomes more valuable. Therefore, a trader who buys a put anticipates the stock price will decrease.

Conversely, a put seller benefits when the stock price trades above the option’s strike price. If the stock price does remain above the put’s strike price, the put’s price will trade towards $0 as expiration approaches, and the put seller will keep the premium they sold the option for. If the stock price drops below the put strike, it’s bad news for the put seller. This is because as the stock price decreases, the put becomes more valuable.

The put seller will have losses for as long as the put is worth more than they premium they collected when entering the trade. Therefore, a trader who sells a put anticipates the stock price will remain above the strike price.

Let’s look at a visual to demonstrate these concepts!

Put Option Trade Example

In the following example, we’ll analyze a put option with a strike price of $95. Be sure to compare the stock price to the strike price of the put, and see how that translates to changes in the put’s value.

As demonstrated here, the put price increases when the stock price drops further and further below the strike price of $95. Why? Because the ability to sell shares at a higher price becomes more valuable as the share price decreases.

More specifically, the stock price dropping from $95 to $90 results in $300 in profits for the put buyer because the option’s value is $3 more than the trader paid for the option. Conversely, the put seller in this scenario would have $300 in losses, as the option is $3 more than they sold it for. However, at expiration, the put seller makes a $300 profit because the option expires out-of-the-money. On the other hand, the put buyer loses the full $300 they paid for the option.

At expiration, neither trader would have a stock position, as the option expired out-of-the-money. However, if a put option expires in-the-money, any trader who holds the option through expiration will end up with a stock position. For a trader who is short the put, the resulting position will be +100 shares per contract. Conversely, a trader who owns the put will have a position of -100 shares (a short stock position) per contract. The share entry price for both traders is the put’s strike price, less the amount the option was bought or sold for.