Last updated on February 16th, 2022 , 01:49 pm

Highlights

- Stop-loss orders are market orders in disguise. Market orders risk horrible fills for options traders

- For better execution prices, stop-limit orders are recommended

- The volume, open interest, and bid-ask spread should all be taken into consideration before placing a stop-loss order on options positions

Stop-Loss Order Definition: An order placed with a broker with instructions to either buy or sell a product(s) at the market price when the price of that product reaches the parameter set.

Stop-Loss Orders in Options Trading Explained

When rookie investors are looking for a way to exit a trade, they are given four primary options; market order, limit order, stop-limit order, and stop-loss order.

Stop-loss. It sounds like a good idea, doesn’t it? If you wanted to exit a position when it met a certain threshold but weren’t around yourself to watch the position, setting a stop-loss seems like a no-brainer.

If your call option contract is trading at $3, you could set a stop loss at $2 and fuhgeddaboudit. After all, won’t this order type prevent any losses below the $2 level?

No!!!

Stop-Loss Orders Don’t Guarantee Where You’ll Get Filled

What you don’t know when you place a stop-loss order on an options contract(s) is where you’re going to get filled. If you place that $2 stop-loss order tonight and the stock gaps down huge in the after hours, you could very well sell that option when the market opens tomorrow for not $2, but $0.50.

Why?

Stop-loss orders are simply market orders in disguise. The price you set in a stop-loss simply instructs your broker when to place your market order. From the perspective of a market maker, all they ever see is a market order, or, free money to them!

Stop-Loss Orders: A Cautionary Tale

When I was working on an options trade desk, one of the most common complaints we had pertained to fill prices on stop-losses placed on options trades.

I have seen sell stop-losses set at $3 on an option contract get filled for $0.05 cents on the open, only to trade at $1.00 a few moments later. We used to call stop-losses on illiquid options donations to the market makers’ holiday fund.

Before we get into why placing stop-loss orders on options contracts can sometimes be a very bad idea, let’s do a quick overview of the various order types, starting with a market order. After all, market orders are simply another name for stop-loss orders.

Option Order Types Explained

Though the below order types can be applied to numerous financial investment vehicles (futures contracts, stocks/equities, ETFs), we are going to focus on options. When compared to other markets, those of calls and puts can be considerably less liquid.

1. Market Orders in Options Trading

In options trading, a market order tells the marker makers you want to be filled on an option position immediately. You do not care what price you get filled at, so long as you get filled that moment.

Market orders are often filled within a fraction of a second of being sent. Think about that for a moment. If you were to sell (or buy) any product, wouldn’t it feel like you were getting the short end of the stick if somebody bought (sold) that product from you in under a second?

A market order tells markets makers that you’re willing to buy/sell your option(s) for whatever price they are willing to give you.

Market orders are essentially freebies for the market makers; everybody wants the other side of a market order, particularly Citadel and Virtu!

How Market Orders Work in Options

Though your broker has a fiduciary obligation to get you the best execution reasonably available on your market order, there is little transparency to this system. Trust me – in my fifteen years as an options broker in Chicago, I have seen some horrendous fills on market orders in options markets.

So how does it work?

Every time you send a market order, your broker engages in a mini-auction on your behalf, with market makers, sort of like eBay. All of the best bids/asks are gathered, and the best one gets the other side of your trade. Sounds like a good system, but remember; not all products auctioned on eBay sell at their fair market value.

With market orders on call and put contracts, you have no idea where you are going to get filled. You are at the complete mercy of the market makers. If you are trading a tight and liquid market like AAPL or SPY, chances are, however, you’ll be fine (more on this to come).

The best order type to use on options (and the only order type I ever use) is a limit order.

2. Limit Orders in Options Trading Explained

A limit order tells your broker that the your limit is the bare minimum fill you will accept. This order communicates to your broker that you are unwilling to:

- Buy an option(s) above your specified limit price

- Sell an option(s) below your specified limit price

Limit orders are always the best way to both enter and exit options trades. Unlike market orders, with a limit order, you know the price at which you’ll get filled. Sometimes, you’ll even get filled better.

For traders looking for immediate execution, it is wise to place your limit order at the “mid” price to try and get the best execution. The mid-price is set smack dab in the middle of the bid/ask spread, and will usually be shown on the order-entry page of your trading software.

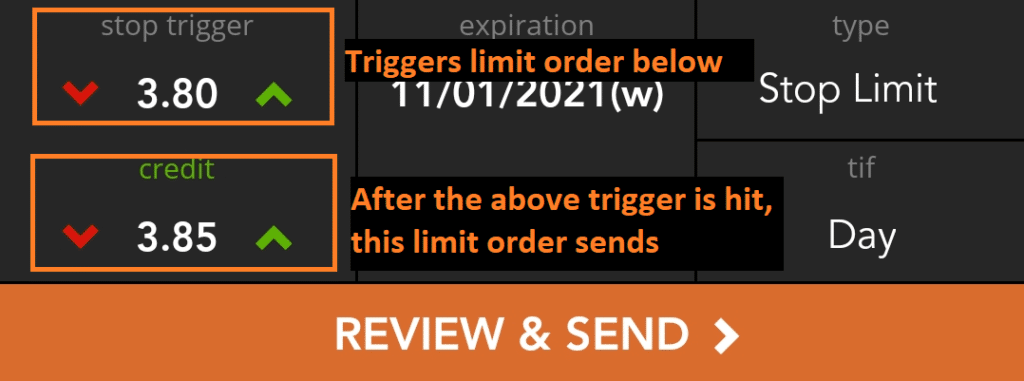

3. Stop-Limit Order in Options Trading Explained

A stop-limit order tells your broker to execute a trade at a specified price, or better after a specified stop price has been breached. A stop-limit order must therefore have two components: a stop order (which is simply a “trigger”, not a true stop-loss) and a limit order.

Take a look at the below image. In a stop-limit order, the stop price triggers a limit order. Remember, in a stop-loss order, the price triggers a market order.

Stop-Limit Order on SPY

Stop-limit orders are a great risk-management alternative to market orders. Why? You know that your position will never be closed at a price worse than the limit set.

The downside of a stop-limit order is that if the option blows through the limit you set, you won’t get filled. This is indeed a huge risk.

Stop-Loss Orders on Options and Liquidity

So now that we know what different types of order types you can place, let’s get back to that nasty stop-loss order and see why it can often be a bad idea.

Poor fills on stop-loss orders and poor liquidity often go hand in hand.

Illiquid markets almost always mean poor fills. Liquidity simply means the ease at which a security can be converted to cash without having an effect on the market price of the underlying. This means high volume and a tight bid-ask spread. More market participants mean greater liquidity. In order to get an idea of a stock’s liquidity, all you need to do is look at the daily volume.

For options contracts, this can get a bit more complicated.

Liquidity in Options Explained

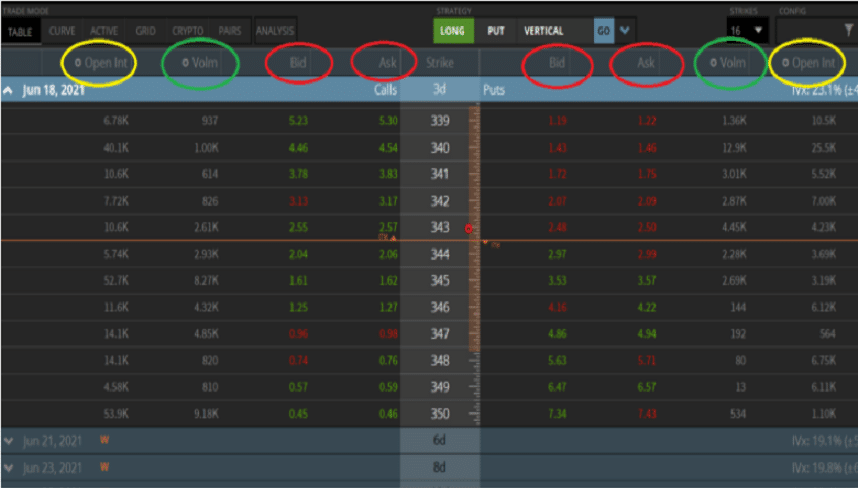

There are 3 important things to consider in this option chain before you place a stop-loss order. You can remember them as the three kings of liquidity. Using the below options chain (from tastyworks) as a point of reference, let’s next take a look at each of these three kings individually.

1. Liquidity and Bid-Ask Spread

Take a look at the bid/ask spread for this option chain, located under the red circles. Notice how tight these markets are? Usually, the options closest to being “at-the-money” are the most active and therefore the most liquid. QQQ was trading at $343/share when this screenshot was captured. The markets are only 2 cents wide at this 343 strike.

Now in an ETF like QQQ, a stop-loss order (aka market order) probably won’t hurt you too badly. Though bear in mind we are looking at an expiration cycle that expires in a few days.

The further out you go in expiation, the wider the spreads get, even on QQQ.

2. Liquidity and Open Interest

The open interest on an option (as shown under the yellow circles) represents the total number of contracts that are held by traders in active positions. The higher the open interest, the better the liquidity. Take a look at the open interest for the 345 calls, over 52k contracts, wow! That’s a lot of liquidity.

3. Liquidity and Volume

The volume of an options contract (shown in green) tells us the total number of contracts traded on any given day. We can see that the volume for QQQ is exceptionally high. Some strike classes, such as the 345 Call, have traded over 8k contracts already, and the day isn’t even over!

The above three technical metrics should give you a good idea as to the liquidity of a particular stock’s options. A stop-loss order in the QQQ market wouldn’t hurt us too badly. But what about if we were trading the options of a more exotic and less popular stock?

Stop-Loss Orders in Illiquid Markets

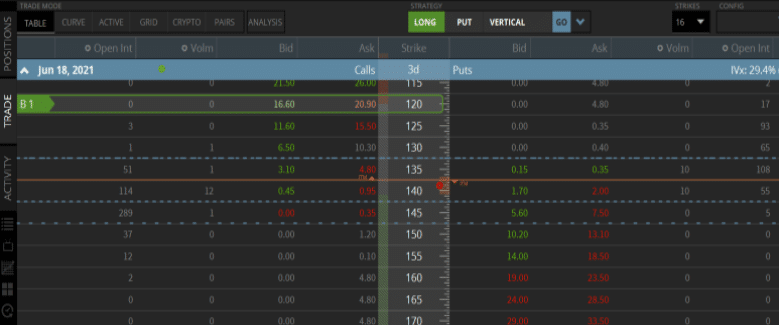

Below is the option chain for Jacobs Engineering Group Inc, (from the tastyworks platform) which trades under the symbol “J”.

"J" Options Chain

Judging from the options chain above, we can tell the symbol “J” is very illiquid. The markets are so bad, not one of our liquidity requirements are met at all. Let’s go through the three kings of liquidity one at a time for J next.

3 Reasons Why "J" is Illiquid

1.) First off, we are going to take a look at the volume of this stocks options. Most of the calls and puts on this stock have a volume of zero. This means they haven’t traded all day. This should be a red flag: strike one

2.) Next, let’s take a look at the open interest. For the vast majority of put options in this particular series, the volume is 0. Additionally, this is what is called the “front month” expiration series, which means it should be the most liquid of all the options expirations for this stock. Generally, for every expiration cycle, you go out, the less liquid the options will be. Strike 2.

3.) Lastly, let’s take a look at this stock’s bid/ask spread. The at-the-money call (140 strike) is 0.45 bid / 0.95 ask. That’s a 0.50 cent wide market, and it doesn’t get much better. If you traded off this spread, you’d lose 0.50 cents immediately. Options markets generally get wider the further you deviate from the at-the-money strike. For example, the market on the 150 call is 0 bid /1.20 offer. Strike three.

Placing a stop-loss on an option in this stock could very well mean a poor fill. For an investor wishing to hedge their risk in J, a stop-limit order would make far more sense.

What Exactly “Triggers” a Stop-Loss Order?

There is no straight answer for this one. At tastyworks, a sell-stop option order is triggered by the ask price. This means that as soon as the option’s ask price falls to our set stop-price, the stop-loss is activated and a market order to sell is sent. For buy stop-loss order at tastyworks, a stop loss is triggered when the bid reaches our stop price.

Many brokers have different triggering mechanisms for stop-loss orders. Sometimes, you can even choose what triggers your stop order. For example, you can sometimes set up a stop-loss order to trigger when the option “marks” at a particular price. The “mark” of an option is exactly in the middle of the bid and ask.

Setting your own triggering method for a stop-loss order can help to give you a bit more or less wiggly room as well. If you set a sell-stop up to trigger off an options ask, that will trigger faster than if you were to set it up off the options bid.

Final Word

We looked at stop-loss orders mostly through the “worst-case” lens. If you are trading a product with great liquidity, chances are, your fills should be decent. This isn’t guaranteed, however. Having a stop-loss order get filled on the open can be devastating no matter how liquid the security.

Sometimes, due to life situations, stop-loss orders are necessary. It is therefore wise to only trade options on liquid products.